By Pooneh Nedaei,

Editor-in-Chief of Shokran Magazine/ Iran

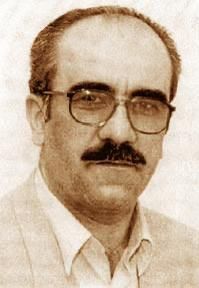

TEHRAN: When we talk about the history of Iran’s press, we shouldn’t just imagine yellowed newspapers or bold headlines from the Qajar era. We should think of the man who devoted his life to turning these seemingly forgotten papers into precise traces of history—not with nostalgia, but with the precision and care of a surgeon. That man is Seyed Farid Qasemi.

Qasemi cannot be summed up in a single title. Although he is widely known as a “researcher of press history,” his work goes far beyond library research. He is more like a cultural archaeologist—someone who, with his own hands, uncovers not just information, but also meaning, context, and historical connections from layers of forgetfulness. He is not merely a recorder of data; he is the living mind and voice of Iran’s press history.

Word by word, page by page, year by year, he has searched through dusty archives and fossilized newspapers to uncover clues that tell us what the media in Iran has gone through, how it was formed, and what became of it.

Qasemi sees the press not just as a tool, but as a living being. That’s why in his writings, although they are full of data, nothing feels dry. He tells stories. He creates narratives. He brings people out of headlines. He awakens the memory of society.

Anyone who truly wants to understand the history of Iran’s press today must engage with his work. Because Qasemi has not only identified sources, but also cleaned, categorized, and published them with meticulous care in hundreds of books and thousands of articles.

For him, what matters is not only what was written, but also when, why, by whom, and in what context it was published. This structured perspective sets him apart from many other writers and even media historians.

Years before concepts like a “National Press Archive” entered institutional agendas, Qasemi had already created a personal archive in his own home. He collected old newspapers and magazines, rare issues, historical ads, critiques, and articles for research—and a few years ago, he donated them to several libraries, including the Astan Quds Razavi Library.

Seyed Farid Qasemi was the first to show that even a two-line advertisement published in Ettela’at newspaper in 1929 could reveal something about the social status of women at that time. Or that a local editor’s note from the 1960s could signal the rise of regional intellectual movements.

He knows how to place details together so the bigger picture emerges. And this is the hallmark of a true historian—not just a collector, but an analyst.

Qasemi is obsessively precise with words. At times, it seems as though words line up before him, waiting to be chosen.

This precision is not limited to his writing. Even when he speaks about press history, he arranges words carefully, respectfully, and thoughtfully—because for him, dealing with history is a responsibility.

Part of Qasemi’s influence lies in this very respect for his subject. He believes that if we neglect the press of the past, it will, in turn, strip our future of credibility.

Seyed Farid Qasemi is not just a researcher of press history; he is a living memory, a cultural processor, and an essential figure in understanding the evolution of media in contemporary Iran.

In a world where everything is quickly forgotten, it is people like him who remind us that “learning from the past” is not just an intellectual pursuit, but a professional duty.

His words deserve to be read and reflected on again and again:

“Recording experiences is the foundation of theorizing, and studying the past is the basis of development.”

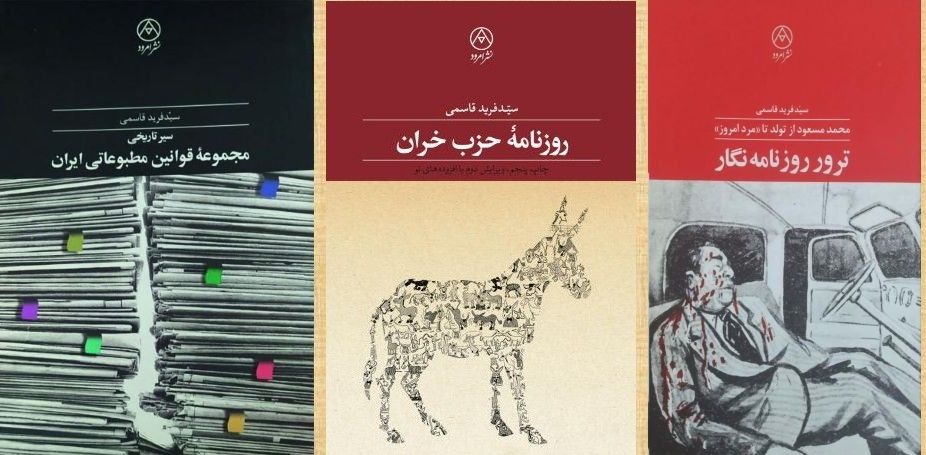

At the end, I had the opportunity to publsih 4 of his famous books in my publishing company; Amrood.

I wish him a long life and good health.