Mangi on the Mic: Bringing Sindhi Rap to the World

Exploring the millennia-old Sindhi culture through Babar Mangi’s hip hop music.

By Rahul Aijaz,

Writer & Filmmaker, Film N’ Chips Media Productions

KARACHI: Rapper Babar Mangi may have broken out with Aayi Aayi in Coke Studio, but his journey to the top of Sindhi hip hop started way back. Born and raised in Sukkur, Mangi tried many things before he became known for rapping and music production.

“We didn’t have a lot of money growing up so we hustled a lot,” says Mangi. “I did photography, made videos for students, and did graphic designing to earn a little. We had a small business called Fortygraphy, which did quite well back in the day when I was 13 or 14 years old.”

Growing up, his father bought him a camera which he “used to earn a few bucks with” and bought himself a Zoom H1. He would often write verses and record them on the device.

“I would record them in our car because there was a vegetable seller who used to come and shout in the street daily and it would mess up my recordings,” says Mangi, adding how he used Magix Music Maker and Audacity to make beats and mix his compositions.

Years before Busin ja Dhika and Gareeb ka Bar, in his teen years, Mangi wrote his first rap – a diss track about a former friend whom he had a conflict with that involved his girlfriend.

“I couldn’t fight so I wrote a diss track about him,” Mangi laughs. “It gained 70 or 80k views back in the day.”

However, that was not the formal beginning of his music career. He moved to Karachi to pursue filmmaking. But as he studied at SZABIST, he realized filmmaking was not for him.

“I can’t be on set for 30 hours. I need some peace to be able to create. I was already doing music then and took some more courses during my studies. I helped others in their thesis films. So, it became a part of me through the process.”

Film education certainly helped him be an all-rounder since he is very much hands-on in the production of his music videos. And he admits that.

“I realized people don’t try many different things. You must try and fail and learn. You must do it quickly so you fail fast and then succeed.”

It is easy to notice that Mangi is completely obsessed with his craft and has spent nearly a decade perfecting it. And like all artists, his upbringing and childhood has had a big role to play in it.

“Artists write more about the past. So, my time in Sukkur plays a part in my work. I got all the stories and experiences while living there.”

Mangi also discusses how he found home in rap more than traditional singing.

“In hip hop, it’s relatively easier to express yourself. In traditional singing, you need to perfect your vocals before you start. But in rap, rawness can also be appreciated so you can start early.”

He says if he were a singer, he would have spent more time learning before he started performing. “In rap, I just straight away went into it. There was nobody around to teach me so there were no limitations.”

In terms of themes that rap allows him to explore, he once again believes there are no limitations. “I feel you can talk about anything in hip hop. It’s also a personal genre where you can showcase your personality more freely. It’s not just a counterculture phenomenon in which you rebel against the system, but also against yourself. You can be more vulnerable.”

One can see that vulnerability and openness in his writing – the way he mixes the personal struggles with the social realities of Sindh. Add in his signature humorous style and the music becomes a fun experience that also shows the society the mirror. That is the reason why his music connects with the masses, especially in Sindh and across the Sindhi diaspora in the world.

His use of Sindhi language is deliberate too. In a country where the mainstream music, film and arts are dominated by Urdu language, artists speaking in other languages are often sidelined.

“People used to tell me not to rap in Sindhi,” he says. “I found it weird because it’s a fresh culture that hasn’t been presented to the world. If we showcase it well, people will like it. People like new things. As I started doing it, I saw more people coming forward. If we don’t believe in our culture, how will it grow?”

He addresses the isolation he faced when he first moved to Karachi – where Sindhis coming from other parts of the province are often discriminated against.

“When I first moved to Karachi, I would feel alienated being a Sindhi in the university. And I used to say, “You all live in Sindh, you guys are supposed to learn to speak Sindhi. Why are you making me feel unfit to be there and alienating me just because I speak Sindhi?”

People’s perception of Sindhis as only a ‘wadera’ (feudal lord) had a lot to do with this. But that’s slowly changing as more Sindhi artists come forth and showcase the native culture which has long been pushed aside.

“Now I see people have started taking ownership of the Sindhi culture.”

He says, “But there is still a long way to go because I see people distancing themselves from Sindhi arts and music. Even some Sindhi artists only create music in Urdu because they think it will get them more viewership. If you don’t believe in your culture, then who will?”

While Mangi is proud to claim Sindhi culture, he is not deluded to the ground realities of the province. Yes, Sindhi culture goes back several millennia and is incredibly rich and remains under-represented in music, film and arts. But the current state of the province – thanks to decades of state-level corruption, theft, deliberate marginalization and growing unrest and poverty – is nothing to be proud of. That leaves us today with no modern heroes to look up to, no new achievements to pass on, and no new stories to sing about.

Mangi wants to change that too.

“I think we are a people who are overly proud of ourselves. We talk about the kind of people we are and celebrate our past achievements in our music and art but we haven’t exactly evolved and achieved anything as of late. What are we so proud of?”

Mangi’s mantra is: instead of fighting it and criticizing everyone, let’s give people something to be proud of. “Our ancestors achieved a lot,” he says. “And we should try for the same.”

He believes if we have legendary Sindhi poets such as Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and Sachal Sarmast, they shouldn’t only be talked about in literary festivals but should reach more and more people. The format needs to change so that a wider audience is aware of our art.

“We are just proud that we create great art but we aren’t bringing it to the people so the world sees it. We are under-recognized in that way.”

Sindhi artists have begun attracting mainstream attention in recent years but there is more room to grow. “The issue is that there aren’t enough Sindhi artists producing art and music in Sindhi. That’s why the organizers and brands don’t believe that there would be an audience for them. Now they have begun creating but not on a large enough scale yet. How many Sindhi artists can you find on Spotify? There is an audience but we need to start creating work. We need to show people that. A Ho Jamalo (a Sindhi folk song) rendition on YouTube would have more than 30 million views. Where are these people coming from? These people exist and we need to start making art for them and push it into the algorithm so everyone recognizes it.”

So far, his rise as a premier Sindhi rapper and music producer has been a fun ride. And it’s also thanks to his collaborations which allow him to diversify and fuse with artists of different styles and genres, especially Amjad Mirani, with whom Mangi partners up with often. In Manig’s words, his own humorous touch complements Mirani’s intellectual and poetic approach, making them a good team.

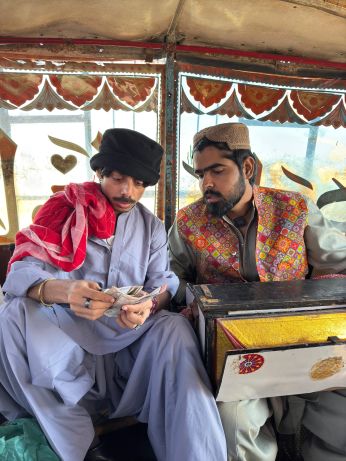

Their tracks such as Busin ja Dhika went viral earlier this year and garnered praise from across the subcontinent and many other countries. The title literally translates to the push-and-shove one experiences in local bus rides and explores the bus as a symbol of life where one faces many ups-and-downs.

Released in July, Mangi’s latest song Sanam Sopari – in collaboration with Sahiban and Muhammad Masood, whose music video is directed by Imran Baloch – is a hyperlocal folk song set in the desert region of Tharparkar, the area and culture whose stories, sounds, and people rarely make it into the mainstream narrative, even within the country.

The track also features Borindo, a 5000-year-old wind instrument from the Indus Valley Civilization and elements of traditional Thari weddings like ‘Sera’ – a communal style of acappella clapping and singing by women.

Baloch’s direction captures the signature beauty of Tharparkar and its people while Mangi provides the perfect soundtrack. The package becomes a love letter to Sindh where diversity and colours are not just welcome, they are celebrated.

It’s evident that these ideas of love, peace and at the same time, self-reflection and harmony are embedded deeply throughout Mangi’s work.