NGOs, INGOs facing tough rules and regulations in Pakistan

The local as well as international non-government organizations operating in Pakistan have recently been receiving strange signals from the government. First, the government began scrutinizing NGOs and INGOs working in different fields across the country and then devised the new strategic policy of INGO registration besides also introducing strict terms and conditions for local NGOs that encompasses auditing of funds and imposition of taxes.

It all started back in October 2015 when the government announced its policy for regulation of INGOs in Pakistan, which only worked to further deteriorate the difficult working conditions many international humanitarian and human rights groups found themselves in. The new regulations required all INGOs to register and obtain prior permission from the Ministry of Interior to carry out any activities in the country and restricted their operations to specific issues in certain geographical areas. The Ministry of Interior is broadly empowered to cancel registrations on grounds of “involvement in any activity inconsistent with Pakistan’s national interests, or contrary to Government policy”. Previously, organizations were registered through the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), which focused primarily on financial oversight of INGOs.

“NGOs working against strategic, security, economic, or other interests of Pakistan will have their registration cancelled,”—a statement found in a press release of the Interior Ministry categorically denying acceptance to organizations that failed to meet requirements.

Earlier this year, the Interior Ministry initiated the process of scrutiny and registration, granting approval to 73 INGOs to continue working in the country. Meanwhile, 23 INGOs were refused permission to operate because of issues with their previous performance and/or due to certain activities falling outside their domain and stated purpose of their organization. 20 or so cases of INGO registration were further deferred; they still await consideration by the Interior Ministry.

On the same line, all INGOs were directed to receive their annual financial audits from any one of the audit firms approved by the State Bank of Pakistan. Cost of audits would be the responsibility of said INGO.

According to the Interior Ministry, the registration of INGOs was critical for the security of the state. And acting as per new policy, the Interior Ministry in its recent move ordered Medicins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders, MSF)—a medical charity that has for 14 years been working in the war-torn Kurram district of Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) bordering Afghanistan—essentially to “pack up and leave”. The move was obviously part of a larger clampdown on the operations of local and international NGOs across the country. This action resembles what occurred a few years back when the government issued a “pack up” order to Save the Children, an organization that had been working in the Pakistan for decades. Later, however, under international pressure, the Pakistani government allowed the organization to continue working but at a very limited level. The result was that overall international charity operations declined to a dismal twenty percent.

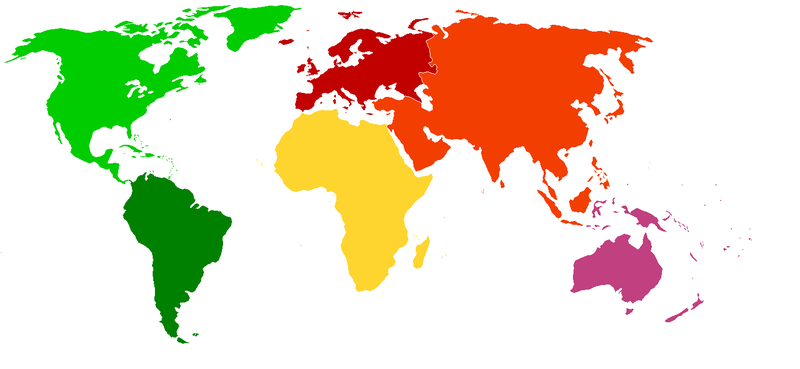

Such recent actions against INGOs have been sending rather confusing mixed messages. Requirements and demands that all INGOs be registered according to Pakistani standards and be monitored for their work may be understandable, but a number of NGOs have been forced to shut any and all activity. Many have been restricted from working in the provinces of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and southern regions of Pakistani Punjab.

Another severe blow that has been dealt on non-profit groups is a new tax that has made humanitarian agencies cut back on services to some of the most vulnerable groups in the nation.

Pakistan imposed a tax in June this year on NGOs that spend 15 percent or more of their budget on administrative costs. Those costs would be taxed at a rate of 10 percent, as would any remaining money at the end of the fiscal year if it totals more than 25 percent of the organization’s entire budget.

Critics see the new tax as part of an ongoing crackdown on civil society, which has seen NGOs stripped of their charity status, shut down, accused of promoting blasphemy and pornography, and forced into a labyrinthine registration process. The government denies allegations of crackdown and says the new law is simply intended to cut down on wasteful organization activities to make sure that donor money given to charities actually makes it to those in need.

“We have imposed taxes on the NGOs to stop misuse of the funds,” said Ishaq Dar, a senator who was finance minister until the incumbent cabinet was dissolved after a 28 July Supreme Court ruling forcing Nawaz Sharif to step down as Prime Minister for charges of corruption. Dar was again chosen for the same position by the interim Prime Minister despite corruption cases.

“If the NGOs keep working in the prescribed limits, they won’t have to pay the taxes,” Dar had said in an interview. “Instead, they will actually have more money to spend on humanitarian programs.”

On the other hand, Nasir Panhwer, who heads the Center for Environment and Development in Sindh Province, told The AsiaN, “It’s not so simple,” adding that the government’s imposition of a tax on agencies that spend less than 75 percent of their yearly budgets on programs would damage current charity efforts.

“The government’s taxes will definitely force NGOs to abandon numerous projects,” he said, further saying that some donors have already suggested they may cease their funding as they do not want funds to be used to pay the new tax.

“You may judge the gravity of situation from the latest reports that besides ‘taxing NGOs for helping the poor’, the government has decided to monitor their activities through the Intelligence Bureau,” Panhwer said in reference to media reports, concluding, “This would leave a very adverse effect on NGO operations.”

Similar views were expressed by an official of another NGO member who asked that his identity not be revealed for fear of any government retaliation, “You know the situation and I cannot take the risk.”

According to a report by the United Nations Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN), the finance minister of Pakistan altogether denied that the government has been cracking down on civil society in order to silence opposition.

Still, civil society leaders beg to differ. Among the major incidents that have been brought to light, they point to an addition to the latest tax move—heightened investigations launched earlier this year into allegations that multiple NGOs were promoting blasphemy and pornography.

Although India has likewise imposed similar regulations on NGOs and INGOs such as issuing notices for over 1200 NGOs to be repositioned. International bodies like Human Rights Watch consider Pakistan’s latest policies to go against basic rights to freedom of association. “Pakistan’s government has the responsibility of preventing fraud, financial malfeasance, and other illegal activities of NGOs, but Pakistan already has laws and regulations that address such concerns,” Human Rights Watch said in a recent statement, going on to say, “The new regulations will severely restrict rights to freedom of association and expression for Pakistanis who are working for INGOs, as well as for foreign nationals. These rights are protected under the Pakistani constitution and international law.”