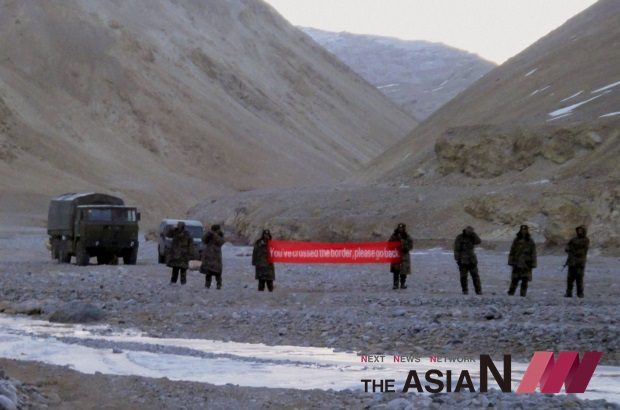

Military standoff between India and China at Doklam Plateau

On July 2015, Indian member of Parliament Shashi Tharoor, speaking at the Oxford Union Debate, made pertinent comments regarding the British.

Making references to a common phrase used to illustrate the sheer extent of Britain’s power in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, he said, “No wonder that the sun never set on the British Empire, because even God couldn’t trust the English in the dark.”

Come to think of it, a point comes up in hindsight as Britain started to retreat in the early 1900s. Elite and small-time politicians in the countries under British rule emulated the British to take hold of the politics in their own countries.

British left behind a mess in several countries before it handed over governance to local political parties and their Parliaments. India was amongst these countries.

After 70 years, India and Pakistan are still struggling with the border issue of the state of Kashmir that was acceded to India during the partition.

The current standoff between the Indian and Chinese army at border tri-junction with Bhutan at Doklam is yet another example of a mess that was left behind by the British.

It is alleged that recently Indian troops stepped in to support the Royal Bhutan Army after the Chinese People’s Liberation army refused to stop construction for a road leading into Bhutan. China had claimed that it was the Indian soldiers who crossed the boundary into China and interfered with the construction.

The 89-square kilometre Doklam plateau has remained a disputed territory since 1955.

According to Neville Maxwell, a retired Australian-British journalist who covered the 1962 war for The Times, “The root of the Doklam standoff is certainly historical”. In an interview with the Indian Express, Maxwell says, “Asked in Parliament, by pre-arrangement, about the alignment of India’s border with Tibet, the (Indian) Prime Minister (Nehru) replied that “the frontier from Bhutan eastwards has been clearly defined by the McMahon Line which was fixed by the Simla Convention of 1914”.

Members (of Parliament) pointed out that China’s official maps, ignoring the McMahon Line, showed India’s North-East Frontier Agency as part of China. Nehru replied that they had been doing that “for the past thirty years”, but brushed that cartographic contradiction aside as irrelevant. “Our maps show the McMahon Line as our boundary, and that is our boundary, [Chinese] map or no map. That fact remains and we stand by that boundary and we will not allow anybody to come across our boundary.”

Maxwell further elaborates, “Later events and investigation have shown that India’s “McMahon Line” border claim stands only on a “forward policy”, which advanced British India’s NE frontier by about 70 miles in its final decade, an aggressive action given a fake legitimacy by a diplomatic forgery concocted in London by a senior official, Sir Olaf Caroe.

It is likely that Nehru was apprised of that background by Caroe himself as soon as he (Nehru) became Prime Minister in 1947. The Chinese government learned of it only years later, when it gained access to the diplomatic records filed in the Potala in Lhasa. That did not affect its basic (Chinese) policy, which was to accept all border alignments as they stood when the PRC first came into existence.

According to Ashok Kantha, the former career diplomat who retired as India’s Ambassador to China in January 2016, “The way I look at it, the Chinese intrusion in Doklam and subsequent standoff is part of a larger pattern. China is pursuing its territorial claims in an assertive and muscular fashion, including claims which are contested or sometimes imagined”.

He further said, “For India as well, apart from the fact that the Chinese had intruded into Bhutanese territory and were trying to construct a road, it would have amounted to changing the tri-junction point unilaterally, even though China has committed that the tri-junction would be determined by discussions among the countries concerned, in this case, India, Bhutan and China. There is a written understanding, from 2012, to that effect”.

Clearly, this standoff in context to the Siliguri corridor is a matter of serious concern for India. If the Chinese presence extends to the Jampheri ridge, the whole of North East India would be made vulnerable.

According to Ashok Kantha, India has to look at these developments in the larger context of the upcoming 19th Party Congress in China with nationalism emerging as a major political force domestically and externally; a time when Xi Jinping will try to demonstrate to his political rivals that he stands as the tallest and most powerful leader in China today.