The resurrection, depiction and an encounter with Sultan Akbar Part 1

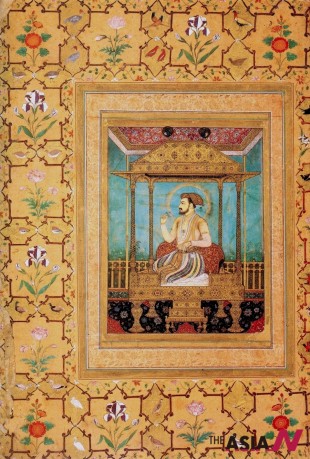

On the journey from Delhi to Agra, I stopped at several locations during which I read pages from the book written by Nizamuddin Ahmad Bakhshi, which gives an account of great conquests and outstanding events of the holy royal presence revealing the icon of the caliphate; the happy Sultan, the just king of kings, the demonstrator of heavenly power, supported by Heavens, the bearer of the throne of grandeur and glory, the builder of the palace of the state and prosperity, the bearer of real and figurative support, Abu’l-Fath Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar Badshah Ghazi; may Allah immortalize his rule and affirm his justice and benevolence!

I was looking for a person with all these qualities. He was highly praised by his vizier and friend Abu’l-Fadl bin Al-Mubarak, the most well-known historian of the age of Sultan Jalaluddin Akbar in his book Akbarnameh, which gave an account of the Sultan’s forty-six-year reign; however, he was equally censured by those who hated him. Between love and hatred, fact and myth, Delhi and Agra and other cities and capitals, I found glimpses of the life story of that man. I even listened and talked to Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar himself; although he died – historically – in 1605, I met him more than four centuries later.

It’s the year 2008. A red carpet is spread not in front of Sultan Akbar’s palace in his capital Agra, India, but on the stairs of a huge glass pyramid in Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan, a Russian Federation republic.

Sultan Akbar will disembark from the vehicle which carried him, and wave to the public who stood on both sides of the carpet leading to the large theatre, as if listening to the song “Shahenshah” (king of kings) by his lovers.

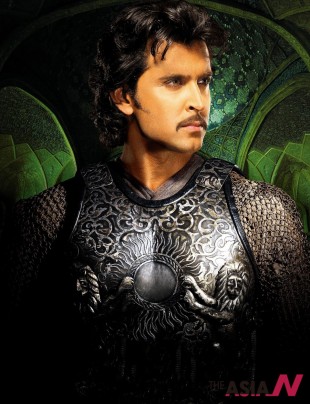

I looked closely at the man who revived the character of Sultan Akbar 400 years after his death: actor Hrithik Roshan, who had come to present his film Jodhaa Akbar at the ‘International Golden Minbar Festival of the Muslim World’s Cinema’ (renamed Kazan International Muslim World’s Cinema Festival). He comes from a family of artists; his parents were film producers. He appeared in a Bollywood film as a child, worked as an assistant director for many years and married an actress, before the Jodhaa Akbar film, he played the starring role with his Indian compatriot, Miss World actress Aishwarya Rai, making him achieve stardom and immense popularity, but the historical film was such a blockbuster in India and abroad that Roshan, a few days after we first met him, was awarded the best actor prize for his role in the film in the same festival.

I did not spend much time looking for differences between the two sultans as the miniatures in the illustrated manuscripts in Akbarnameh outlined the Sultan’s personality traits which inspired the film, other than those given by the loving historians: signs of power – hunting and taming wild animals and fighting and defeating persons stronger than him, in addition to qualities of mercy and religious tolerance.

We were now in Delhi (or the old name, Dehli) and would proceed to another place which bears the marks of Jalaluddin, such as his capital Fatehpur Sikri in Rajasthan, then Surat in Gujarat up to Agra, the site of Taj Mahal.

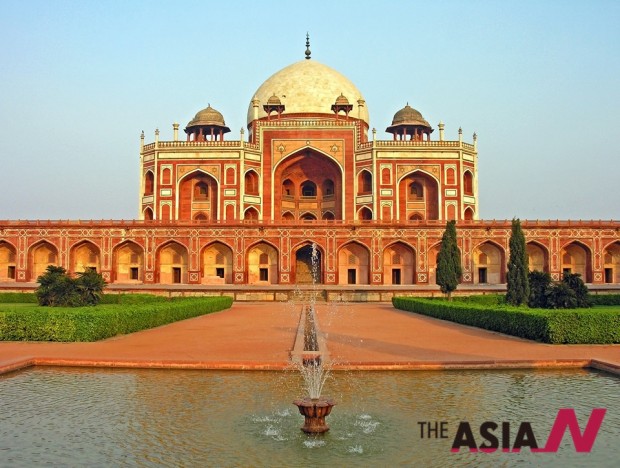

In front of Humayun’s mausoleum

A large geographical area reflects the expanse of the Sultan’s rule, which witnessed military activities, as well as his court which attracted historians, writers and thinkers. It was the base of beliefs and sects and the seat of scholars, some of whom were among his favorites in his private assembly called “place of worship”. We are here in Delhi, which represents with its sultans, the seat of the Hindus and the end of the class of its sultans.

Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar’s father, Sultan Humayun (17 March 1508-7 March 1556) was a grandson of two of the most famous conquerors in Asian battles: Amir Timur (Tamerlane “Timur the Lame”) and the Mongol king Genghis Khan, from whom came Omar Sheikh Mirza, the ruler of Ferghana, father of Sultan Muhammad Babur, the conqueror of India and the grandfather of Sultan Jalaluddin. I found a manuscript by Shaikh Yassin Al-Ajlouni describing his former and later ancestry.

I stood in front of the mausoleum (1530) in Delhi which retains all features of Mogul architecture whose models are seen in Muslim India today: (present-day) India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Kashmir, a style which is the flexible fusion of the traditions of local architecture in pre-Islam India and post-conquest civilization where stone and wood were used as basic building materials. That distinguishes it from Persian architecture in Iran, Turkestan (city in Kazakhstan) and Afghanistan, where sun-dried, baked bricks and pottery mosaic decorations were used. Instead of external decorations, Mogul architecture had inscriptions in stone, plaster marble mosaic, studding and color stone.

The Mogul buildings which we saw during our journey had ground plans – wide courtyards with galleries sometimes roofed with small domes around. The fountain in front of the mausoleum and the gardens around the castles show how they cared about gardening and water, a legacy of the Safavids in Iran. Persian pointed arches (concave upper part) and Fatimid ones (straight upper arch) were common, so were domes with pointed and circular arches, mostly of two layers with a wide space in between, which makes its upper part look like an upside down glass. Galleries were shaded or otherwise, surmounted by a dome or arch, with prominent ledges in the façade, on galleries or below the dome made of large stone boards or marble supported by stone. Supports rather than columns were usually used.

Mogul minarets were made of stone; palm–like ribbed or conically cylindrical, and wall decorations included chevrons, niches and inscriptions. Stone was mixed with a different colored marble such as white marble was a common basic building material. Stone or marble mosaic or precious stones were also commonly used, and pieces of color glass were mixed to reflect sunlight. Color murals, ceilings and supports were used instead of studding to ensure speed and less costs. Color decorations were put on a white lime, plaster or shell paste floor to look like snow-white marble, the masterpiece being the mausoleum of his grandson Shah Jahan and his beloved wife, known as Taj Mahal. That is where our journey, following in the footsteps of Sultan Akbar, came to an end.

Jalaluddin’s rule began at Nouruz, the start of the lunar calendar, mainly a Persian religious occasion (Aries – 21 March). It also marks the start of spring in India. Moguls used to celebrate it for 19 days (12 in Iran).

The sultan’s influence extended in later years through war, siege or peace pacts, and Gwalior, Ranthambore, Terindah, Sikandra, and other castles fell. He used to tame his elephants in Malwa and hunt monkeys in Fairuza, subjugate several areas and provinces and bestow titles upon his allies, including Safavid Shah Tahmasp.

However, just as the Sultan treated his favorites in such a friendly manner, he treated traitors extremely harshly, as he did with Adham Khan Kokaltash, who killed Ataga Khan (Akbar’s vizier) out of arrogance and enticement and rushed to the Sultan Akbar’s inner apartment where the sultan caught him and ordered him to be thrown alive from the palace roof. But as after being thrown once, he was still alive, the soldiers threw him again. This scene in the film Jodhaa Akbar was brutal, but it reveals an important aspect of the character of the ruler, who runs out of patience in situations which do not require such patience.

But the real test of the history of Jalaluddin Akbar is clearly shown in his relationship, as a Muslim sultan, with other religions, which rose in India or came from the east and west.

An encounter with the Portuguese

In the 16th century, the first presence of European Catholics in India was recorded, and Sultan Akbar sent letters to the Catholic missionaries in the port and city of Goa. They came with the Portuguese fleet which arrived at the coast of Goa, Diu and Daman in western India in AH 916/AD 1510 before extending to the rest of the Indian shores and reached the upper Bay of Bengal in AH 944/AD 1537. The Sultan asked the mission to send an envoy to introduce their religion, as reported by Dr. Saad Alghamdi, Professor of Islamic History and Oriental Studies in a paper presented at a conference organized by Faculty of Dr. Al-Olum, Minia University (Egypt) in 2008 (the year the film was screened).

The religious delegation arrived at the Sultan’s court in Fatehpur Sikri in AH 986/AD 1578 representing St. Paul’s Organization. The Sultan was so affected by the delegation’s explanation that he asked a tutor of them to teach his son Murad Portuguese and also wanted someone to teach him the language (though he was illiterate).

The Sultan provided the Catholic rituals as well as those of other religions of his citizens, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Tibetan Buddhism, Sind Shamanism and Brahmanism considerable protection. In addition, he allowed the building of a church in Fatehpur Sikri and another one in Lahore, and afforded the Catholics and other citizens’ freedom of worship and shared in events they organized in Fatehpur Sikri, but refused their request to convert to Christianity.