Kalilah wa-Dimnah: Ancient Asian Folk Tales with Modern Insight

I was almost 13 years when I read some of Kalilah wa-Dimnah’s fables for the first time. Touched by the animal characters in those folk tales, I used to find an equal personification of those animals in real life. For my surprise, I learnt many years later, that the author of those imaginary stories was doing exactly the opposite; he was writing Kalilah wa-Dimnah with kings, ministers and certain people in mind, so, instead of directing those elite, he wrote his wise stories to teach them politely and indirectly.

This was not the only amazing aspect about Kalilah wa-Dimnah, as the well-known Arabic literary classic (8th century collection of fables) that puts wisdom fables into the mouths of animals for the edification of humans was originated around 200 BC in a Sanskrit collection of animal stories. The Arabic translation (Kalila wa Dimna) was originally rendered in the 8th century by Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa in Baghdad, the nowadays capital of Iraq.

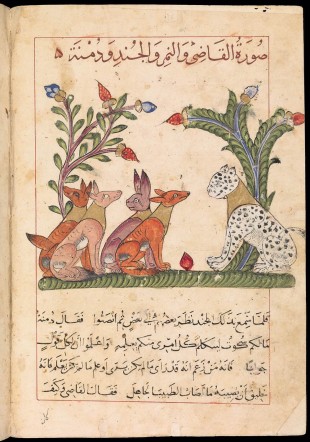

Kalilah wa-Dimnah is considered a translation and expansion of a popular Indian collection of stories called the Panchatantra, also known as The Fables of Bidpai. The translation was made via Persian in AD 750 by ‘Abd Allah ibn al-Muqaffa‘, and was frequently copied. I attach a page of the original book in Arabic, where two scheming jackals that feature in the main story of the work. The caption above the picture shown here reads: ‘Image of the judge, the tiger, the soldiers and Dimnah.’ It illustrates the trial of Dimnah, and teaches the lesson that crime does not pay. Dimnah had been put on trial, and is subsequently jailed and executed, for plotting to kill the king’s faithful servant, the bull Shanzabih.

The origin of Kalila wa Dimna is the ancient Indian book called ‘Panchatantra’ which was first translated by a young Indian physician called Borzoyeh Tabib (Doctor) Marwazi commissioned by Anu Sharwān Khosrow the son of Qabād the Sāsāni king but Borzoyeh did add more tales most of them from other Indian legends.

After the islamization of Iran, Ibn al Muqaffa translated the book into Arabic and called it the Kalila wa Dimna that was based upon the original Farsi and this Arabic rendition. Out of this translation, the legends were translated into many other languages. During the reign of the Sāmānian, ‘Abu ‘Abdallah Roodaki translated (320 HQ or 900 CE) the Ibn al Muqaffa’s version into versed Farsi poetry. And during the reign of the Bahrām Shah Ghaznavi a writer called Manshā’ again translated the Ibn al Muqaffa’s version into Farsi prose (not versed one). Kalila wa Dimna were taught from the king’s courts down to the grammar schools indeed as a manual for teaching wisdom and conduct in the society.

Like Arabian Nights, this literary work has penetrated so deeply in many cultures encompassing almost every continent of the World. During last 1500 years there are more than 200 translations of Panchatantra in around 60 languages of the world. ‘Aesop fables’, La fountain’s tales, and great many of Western nursery rhymes and ballads have their origin in Panchatantra and Jataka stories.

In European countries there is so much of migration and borrowing of stories over many centuries, making it difficult to finalize their origin at one location in Europe. However, mostly, their Indian origins are not disputable. Traditionally in India it is believed that Panchatantra was composed around 3rd century BC. Modern scholars depending on references to earlier Sanskrit works in Panchatantra assign the period of 3rd to 5th Century CE for its composition in today’s form. The author of Panchatantra is not known.

Panchatantra folk literature migrated to Iran in the 6th century CE. The story is well known. Burzoe, a physician at the court of Sassanian king Anushirvan (531-571 c.CA), was sent to India in search of Sanjivani herb. In search of this medicine he traveled a lot in India and brought Panchatantra to Iran, which he translated into Pahlavi and entitled it Kalilah wa Dimnah. This is the first known translation of Panchatantra into any foreign language. It is not available now but translation done into old Syrian language in 570 CE made by a Nestorian Christian called Bud, was discovered in a monastery in Mardin, Turkey in 1870 CA. The title of this book is Kalilag andDamanag, which is the Syrian version of Karataka and Damanaka, of the two jackals in the first Tantra of Sanskrit Panchatantra.

This Syrian version was edited and translated into German in 1876 CE by Bickell and then again by Schulthess in 1911CE. Syrian translation is very close to Tantrakhyayika in many respects. The next important translation of Panchatantra was done two centuries later in Baghdad, in 750 CE. Abdallah ibn al-Moquaffa a Zoroastrian converted to Islam, working in the court of Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur translated it from Pahlavi. Moquaffa is credited with intellectual and literary development of Arabic prose.

His Panchatantra translation enjoyed great popularity and is considered as master piece of Arabic narrative literature. Almost all pre-modern translations of Panchatantra in Europe have their roots in his Arabic translation. From Arabic it was translated again into Syrian language in 10th/11th century CE and into Greek in the 11th century CE. 12th century CE Hebrew translation made by Rabbi Joel was translated into Latin by John of Capua around 1263-1278 CE which got printed in 1480 CE. From this Latin translation Doni translated it into Italian.

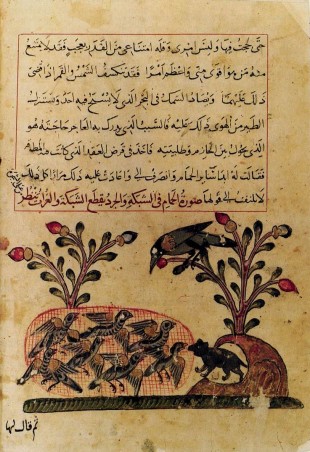

Kalilah wa-Dimnah has inspired many artists and there are many Persian and Arabic miniatures, wall paintings and Vases decorated with stories from Kalilah wa-Dimnah. In Sri-Lanka, a fragment of second or third century CE Indian red polished ware exhibiting crocodile-monkey story has been unearthed. 7th century CE Mamallapuram rock relief has Panchatantra stories and tenth century Bengal Temple has them on molded terra cotta plaques. A 12th century CE Vishnu temple ceiling at Mandapur also is decorated with Panchatantra stories. In Central Asia, at Panjikent 7th and 8th century CE Soghdian artists have decorated walls of their houses with Panchatantra and Aesop’s fables. The artistic penetration of Jataka/Panchatantra tales and their translated versions are fascinating and textual and artistic expressions which should be studied together. In the preface of Kalila wa Dimnah, Ibn al Muqaffa mentions that the reasons for paintings in his text was to provide pleasure to the reader and also to make the reader more aware of the book’s value. Another artwork which became very popular was created by Husain bin ‘Ali-al-Waiz al Kashifi, titled Anwar-i-suhaili at Herat in 1504 CE. This work was very popular in Persian intellectual circle then. For some time this Text was taught to British officials of the East India Company at the East India College, Haileybury during the second half of the 19th century. Abul Fazl in 1588 CE under the instructions of Mughal Emperor Akabar produced another Persian version entitled, Iyar-i-Danish (Criterion of Knowledge. 12th century CE Shuka Saptati, another artwork of Katha literature written in classical Sanskrit was adapted into Persian in 1329 CE. Author Ziya al-din Nakhshabi entitled his translation as Tutinamah. It was translated into German in 1822 CE and subsequently into many other European languages including English by F.Gladwin. Cleveland Museum of Art has some of the best paintings of Tutinama manuscript. In India, Panchatantra stories have become the part of temple architecture along with Ramayana and Mahabharata stories.

Today, any reader refers to Kalilah wa-Dimnah will discover how much it is suitable to match its wise and meanings to the modern lives of our societies, and this is the case of all great folk tales, that were born in Asia to live in the four corners of the world.