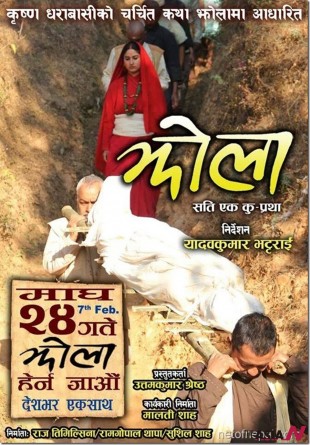

Jhola: A Tale Of Cruelty Against Hindu Women

A movie revealing wicked custom of Nepali suttee

Jhola(Bag), a Nepali movie based on the cruel Sati system that was abolished 95 years ago from Nepal, became the first hit of 2014 in the movie theatres across Nepal. Released in the first week of February, the movie was drawing a huge crowd of movie-goers by the time this article was written. Many aspirant viewers had to return home without watching it as they failed to get tickets. Sati is a cruel system prevalent until 100 years ago among the so-called high class Hindus of Nepal and India. Under this system, the wives had to die with their husband by burning themselves alive in the pyre of their husband. At that time in Nepali society, polygamy was popular among the rulers and dozens of young wives had to burn themselves alive when their powerful husband died.

Based on the story Jhola, written by Krishna Dharabasi, one of the prominent prose and story writers of Nepal, the film is however not about the plights of the wives of powerful men, but of the wives of simple husbands of rural Nepal. The film takes the name Jhola, a Nepali word for bag, as the handwritten script of the story is found in a bag left by an unknown man in the house of the story writer. The plots of the film develop in flashbacks as the writer begins to read the manuscript.

The film opens by showing an ailing old man in his early 70s and his wife in her late 20s in a village located in the hilly region. They have a son who has a deep desire to read and write. But, there was no school in Nepal at that time and the main task of children was to graze the cattle. Popular actress Garima Pant plays the role of the young wife of the ailing man. The old man (Deepak Kshetri) had married her after his first wife died. The poor wife has a tremendous workload from dawn to dusk feeding and taking care of the son and ailing husband, cooking meals, washing dishes, working in the farm, husking rice in the traditional wooden mill, and collecting fodder and firewood.

The list of work she does everyday is beyond the imagination of many city women today. However, the bitter fact is that many women in remote villages of Nepal still live similar lives.

One afternoon, the old husband dies and the real pain of his young wife begins. She is not allowed to speak with anyone and not even allowed to touch her young son. She is told to be ready to become a sati (to burn alive in the pyre with her husband’s body) for a better after-death life. The crying son is kept away from her. The women are unable to control their tears seeing the fate of their young neighbor. Filmmaker Yadav Kumar Bhattarai has presented the pains and pathos successfully in this scene. Finally, the body of her husband is taken to the crematory site and the young wife attired in her bridal clothes follows the body. Instruments are played so that no one hears the cries of the poor wife.

Before reaching the crematory site, she is told to take off her clothes and get naked. She then follows the body of her deceased husband down to the riverbank silently. It is evening and she climbs up the burning pyre and sits crossed-leg next to the lying body of her husband. The small son who follows the funeral procession secretly witnesses all cruelty meted out against her mother by the society in the name of tradition. Yes, some women and men oppose the tradition, but they cannot revolt against the deep-rooted tradition of Nepal in the 1910s.

Now their son starts living with his step brother by looking after his brother’s and his own cattle. He occasionally visits the crematory site where his mother was burnt alive with the body of his father. One day, he happens to see his mother living in a cave of the jungle. She had been hiding in the jungle after she had secretly jumped into the river from the burning pyre by taking advantage of the dark night. However, she was terrified because she knew well that she could be killed anytime if the villagers saw her. She had seen how brutally the widows used to be killed then. Finally, the boy, with the help of his kind uncle (Desh Bhakta Khanal) and auntie (Laxmi Giri), manages to flee the village only to keep his mom alive. On the day of their departure, the poor widow happens to see another young woman being stoned to death in a crematory when she tries to run away. It was the son who had left the manuscript in the home of the writer when he became old.

While watching the movie, the audience could not control their tears. Filmmaker Bhattarai surely deserves kudos for making Jhola, which looks a perfect combination of the story and the movie. Moreover, Dharabashi himself has been a crew member of the beautiful movie that reflects life of rural Nepal in the early 20th century.

Although it is all about the inhuman Sati practice in which the wives have to die with their husbands by burning themselves alive in the pyre of their husband, the movie also portrays the social, cultural and economic aspects of Nepali society at the time as well as the status of women in the fore in a chronological order. For men, women 100 years ago were only machines to produce babies and work for them. Filmmaker Bhattarai has presented this beautifully in the two-hour movie.

As said above, the film mirrors the conditions of the Nepali women in particular and the society in general prior to the abolition of the sati practice by Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher in 1920.

Movie shows many evil social practices

Director Bhattari has tried his best to include all evil practices of the society back then although his focus was on the sati system. He has even shown how the slaves used to be treated then.

All the characters are shown in the attire popular in Nepali society at the time. They walk barefoot and light the house by burning figs.

Senior actors of the Nepali movie industry including Deepak Kshetri, Desh Bhakta Khanal and Laxmi Giri acted in this film. It held the audience spellbound for two hours. It is free of scattered ideas, which has been a common problem in Nepali movies.

The setting and cinematography looks perfect. A non-Nepali audience can also enjoy the movie as it has English subtitles. When the debate of man or machine is rife in Hollywood, Jhola, which has presented women as machines, is indeed a movie worth watching. After a long interval, the fans of Nepali movies have a beautiful film based entirely on the Nepali society of a hundred years ago to enjoy while sitting together with their family members.

Excited by the success of the movie, story writer Dharabasi has taken the movie to the U.S. for its screening there on April 13.