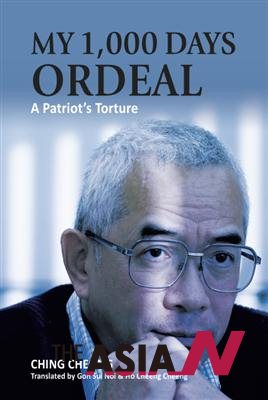

Father of Singaporean nature conservationists

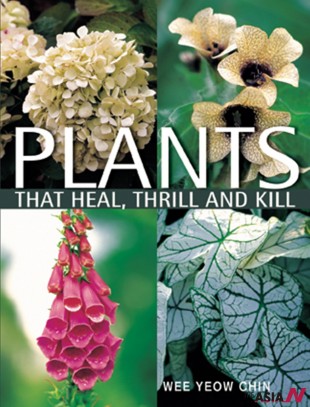

Profile: “Eco-Warror” Dr. Wee Yeow Chin

As a botanist, Professor Wee Yeow Chin was wont to talk to people about plants and animals, if not about birds and bees. His lectures on ferns, mushrooms, lichens and algae, the non-flowering plants that were his specialty, were serious stuff. Yet, the most-frequently-asked question from the lips of listeners was “Can eat or not?” he said in a smattering of Singlish.

Why this fetish of food? My elderly friend Edwin Netto believes this was a legacy of Japanese Occupation days (1942~45) when “Singaporeans had little to eat and had to grow our own sweet potatoes and tapioca.”

After the War, Singaporeans were in the throes of making a living under difficult economic circumstances. In those nation-building days of the 1960s, the Republic fared lowly on the ecological totem pole. As a conservationist, Dr. Wee might be ahead of the times, but he was not against development per se. In his case, after graduating from the University of Singapore in 1964, he found a job at the Malayan Pineapple Industry Board as agronomist and chief research officer at Pekan Nanas in the state of Johor.

“I worked on a flowering mechanism to stimulate pineapple growth and improve the fruit’s yield.”

With this path-breaking research, Mr. Wee went on to earn a PhD and a teaching post at his alma mater. Yet more than a job, his life-long academic career was to thrust him into the unsolicited role of a green advocate.

Up till the 80s, environment was in the backburner in the economically-driven city-state. An indication of this was when the authorities cleared up a habitat of migratory birds in Serangoon estuarine, there was hardly any public reaction. A journalist Ilsa Sharp, however, did bemoan the loss to nature-lovers by her report published in the national daily The Straits Times.

Green advocate Wee

Singapore’s push to achieve a first-world economy continued to nibble away at the edges of the 716.1㎢(276.5 sq mi) today, city-state’s diminishing forest coverage, a mere 5% of its pristine past. Prof. Wee watched with alarm when road and housing construction began to creep up on the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. The nearby hillside quarrying was a threat to the forest ecology.

Using the media platform, the intrepid academic called for a halt to the quarrying. To protect the forest, he also urged the authorities to set up reforested buffer zones that years later enhanced the nature reserve. Then again way-side trees in the city would have been stripped of their festoons of ferns were it not for the passionate naturalist’s timely intervention.

Earlier, zealous park custodians of the trees had been trimming the staghorn ferns from the trees out of concern the fern clusters would collect rainwater and breed mosquitoes or cause branches to rot – reasons that Prof. Wee dismissed as misguided.

Taking on public authorities on such issues led some people to see him as as Don Quixote tilting at windmills. Enthusiastic tree-huggers there might be, but contradicting the authorities was still sensitive. But, someone had to speak out for the conservation cause in the face of on-going encroachments into the lowland forest areas, especially while expanding the network of expressways were expanding.

In 1986, a six-lane road linked to the Pan-Island Expressways (PIE) that sliced through the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve completed, without public consultation. “It was a fait accompli,” said Prof. Wee.

It was to be left to the then Singapore Branch of the Malayan Nature Society (MNS), of which he was secretary and later chairman, to point to the deleterious effects of the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE) – especially the prevention of inter-breeding of plant and animal species. Motorists were soon to witness the killing of monkeys, pangolins and other creatures trying to cross the two expressways at night.

Beyond expressing outrage at the carnage, the public discourse helped crystalline the idea of an ecological bridge to link the Bukit Timah and the Central Catchment nature reserves. In 2013 the hourglass-shaped eco-link, 50 meters wide, was completed, thereby allowing animals and plants to migrate across the two forest zones.

The authorities did not take kindly to open criticism of its development policies. Officials would lean on the local chapter of MNS for allegedly being unduly influenced by outsiders, said Wee.

To assert its independence, the Singapore Branch severed ties with MNS and established itself as the Nature Society of Singapore (NSS) in 1991. Prof. Wee was elected its first president, taking the helm of the non-government organisation that would, in its own right, act as a kind of green conscience and spearhead NGO efforts to protect the environment.

And he was able to show that responsible and constructive, not necessary confrontational, action could achieve good outcomes. Indeed, in 1986 the government was won over by the society’s case for conserving a mangrove swamp teeming with migratory birds in Sungei Buloh in the north-east of Singapore. It had been slated for an agro-technology park.

“You see something is worthy of conservation, you fight for it; not fighting for everything. It is not worth it,” was how Prof Wee described the selective approach to lobbying that worked. He alluded to two conservation bids that were turned down by the government because they were deemed not to be unique eco-systems.

Following up on its achievement in Sungei Buloh, the NSS in 1990 pro-actively drew up a master plan that listed potential sites for conservation. It helped shape the state’s policies on environmental protection and set the pace for the green master plan Singapore submitted for the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The plan was hailed for the government’s pledge to apportion 5 % of its land area, up from the original 3 %, for nature conservation.

The Nature Society’s collaborative efforts won it a Greenleaf Award, annually handed out by the government as a badge of recognition for institutions and individuals that made a difference in environmental protection. Prof. Wee later received the prestigious award as NSS president.

Don Quixote tilting at windmills?

Relations turned sour, however, when the government unveiled a plan for a 36-hole golf course in the Lower Peirce nature reserve. The proposed putting green would have displaced 40,000 trees and disrupted the resident flora and fauna.

Never mind that he was in the good books of the government, the project had to be stopped for the sake of the ecology and for posterity. No self-interest came into play. “I don’t play golf but even as a golfer I wouldn’t support it,” he was later to say. “It was just that golf courses are pollutive in nature.”

Reflecting on the urgency of the task, Prof. Wee and his team feverishly churned out an 80-page report for the government to argue why the golf range must not be. The authorities refused to be drawn. Fearing their appeal had fallen on deaf ears, they took their case to the media. Joining the cause, The Straits Times gave the issue intensive coverage, and quickly created a popular buzz.

Unbeknown to Prof. Wee, a petition against the golf course was circulated and signed by members of the public. “I knew the government would not take kindly to NGOs resorting to petitions,” said the astute academic. Soon two officers from the Internal Security Department came a-calling.

“They asked me about my plans and aspirations for the society. I told them that my interest was in educating the public on conservation and work with government to preserve Nature,” he said. “I offered to put them on the mailing list of our publication Nature but they declined.”

“The meeting was cordial, but I got the sense of its subtle message to me.” He soon noticed, however, that The Straits Times began to tone down its coverage of conservation issues, disclosing that he found out that conservation was then regarded as a dirty word in official circles.

Wee’s teaching and writing legacy

But nature lobbyists were vindicated. In the face of adverse public opinion, the government put off the golf course. The saving of Lower Peirce nature haven marked a high point in the soft-spoken professor’s mission to save Singapore’s precious little nature. The hard-fought success had come at some expense to his personal university career though; he retired in 1997.

But, Dr. Wee’s achievements were not confined to high-profile lobbying cases. Away from the limelight, it was the don’s teachings and writings that had a deeper and lasting impact in lifting the level of environmental awareness and participation. Some have credited him with nurturing citizen-scientists through his series of nature guidebooks for laypersons.

With his more serious works on endangered species and ecology in an urban setting, the teacher-mentor had challenged every concerned citizen to take ownership of their natural heritage.

Indeed, the paternalistic eco-warrior’s enduring legacy was his pivotal role in speeding the bloom of a new breed of environmentally-conscious and caring Singaporeans. In his days, he had dared to walk the talk.

In December 2000, a botanist Joseph Lai on a beach outing on the rustic islet of Pulau Ubin made a fascinating discovery as the tide receded. The sandy shore was coming alive and his trained eyes enabled him to spot marine creatures from anemones, star fish, sponges, molluscs to otopus, cuttlefish, squids, crabs and prawns.

He had chanced upon a rare mix of eco-systems that range from mangrove, coral to forest and seagrass lagoons, the latter a haunt of the elusive dugong or sea cows that many lonesome sailors mistook for mermaids.

News of this jewel of a hidden marine haven at Chek Jawa that only shows itself at low tide thrilled nature-lovers. Unbeknown to them, however, was that the dream habitat had been earmarked in 1992 for reclamation and work was to begin in six months.

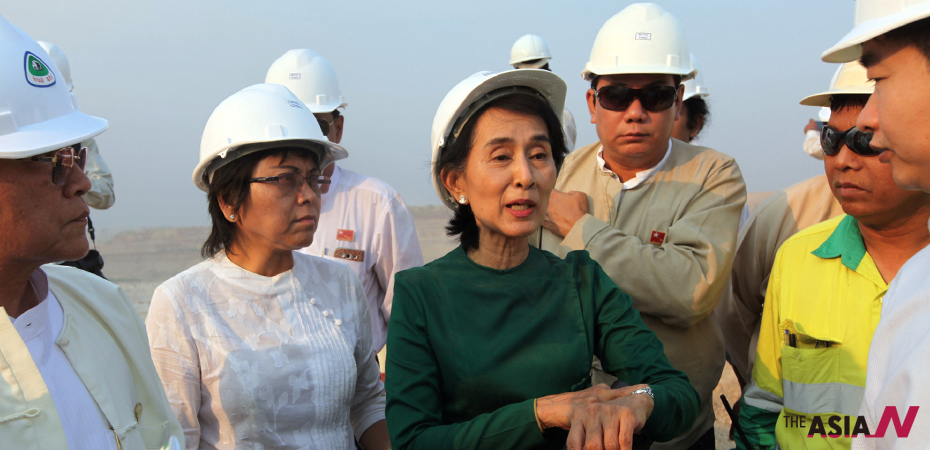

Time was running out. Botanist Joseph sounded the call for urgent action to stop the bulldozers. Thanks to social media, amateur scientists, members of the Nature Society and other volunteers rallied en masse to the cause. Flocking to the site, they helped identify and collect samples of marine animal and plant species. Their well-documented report made for a winning case for preservation. It moved then Minister for National Development Mah Bow Tan to visit Chek Jawa and assess its merits for himself. Giving the government’s nod soon after, Minister Mah added a rider that the haven would be untouched for as long as it is not needed for development.

A worthy case a la Prof. Wee had been fought and won, if temporarily. But, the man who continued to be regarded as an inspiration to nature conservationists in Singapore claimed no direct credit for it.

Nevertheless, Singapore’s foremost green pioneer accolade is deservedly his for posterity. “No lah. I just do what I’ve to do,” Dr. Wee said in his trade-mark Singlish. Always passing frontiers of nature study, the septuagenarian now helms a Bird Ecology Study Group blog he founded in 2005, especially to shed new light on puzzling bird behaviour.