“See you in Pyeong Chang!” Russia closes costly Sochi Olympics

Flushed with pride after its athletes’ spectacular showing at the costliest Olympics ever, Russia celebrated Sunday night with a visually stunning finale that handed off a smooth but politically charged Winter Games to their next host, Pyeongchang in South Korea.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, these Olympics’ political architect and booster-in-chief, watched and smiled as Sochi gave itself a giant pat on the back for a Winter Games that IOC President Thomas Bach declared an “extraordinary success.”

The crowd that partied in Fisht Olympic Stadium, in high spirits after the high-security games passed safely without feared terror attacks, hooted with delight when Bach said Russia delivered on promises of “excellent” venues, “outstanding” accommodation for the 2,856 athletes and “impeccable organization.

” The spectators let out an audibly sad moan when Bach declared the 17-day Winter Games closed. “We leave as friends of the Russian people,” Bach said.

The nation’s $51 billion investment – topping even Beijing’s estimated $40 billion layout for the 2008 Summer Games – transformed a decaying resort town on the Black Sea into a household name.

All-new facilities, unthinkable in the Soviet era of drab shoddiness, showcased how far Russia has come in the two decades since it turned its back on communism. But the Olympic show didn’t win over critics of Russia’s backsliding on democracy and human rights under Putin and its institutionalized intolerance of gays.

Despite the bumps along the way, Bach was unrelentingly upbeat about his first games as IOC president and the nation that hosted it. One of Sochi’s big successes was security. Feared attacks by Islamic militants who threatened to target the games didn’t materialize.

“It’s amazing what has happened here,” Bach said a few hours before the ceremony. He recalled that Sochi was an “old, Stalinist-style sanatorium city” when he visited for the IOC in the 1990s.

Dmitry Chernyshenko, head of the Sochi organizing committee, called the games “a moment to cherish and pass on to the next generations.”

“This,” he said, “is the new face of Russia – our Russia.” His nation celebrated its rich gifts to the worlds of music and literature in the ceremony, which started at 20:14 local time – a nod to the year that Putin seized upon to remake Russia’s image with the Olympics’ power to wow and concentrate global attention and massive resources.

Performers in smart tails and puffy white wigs performed a ballet of grand pianos, pushing 62 of them around the stadium floor while soloist Denis Matsuev played thunderous bars from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No.2.

There was, of course, also ballet, with dancers from the Bolshoi and the Mariinsky, among the world’s oldest ballet companies. The faces of Russian authors through the ages were projected onto enormous screens, and a pile of books transformed into a swirling tornado of loose pages.

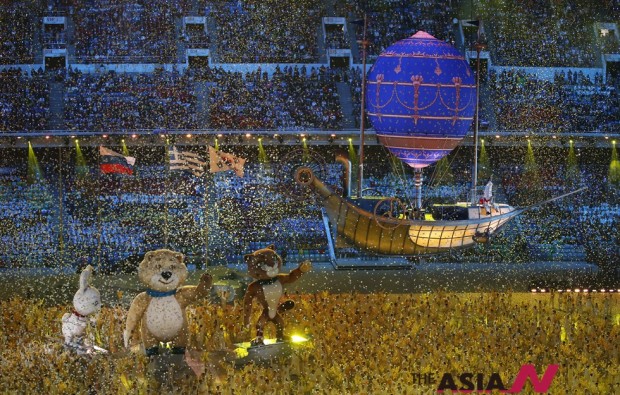

There was pomp and there was kitsch. The games’ polar bear mascot – standing tall as a tree – shed a fake tear as he blew out a cauldron of flames, extinguishing the Olympic torch that burned outside the stadium. Day and night, the flame had become a favorite backdrop for “Sochi selfies,” a buzzword born at these games for the fad of athletes and spectators taking DIY souvenir photos of themselves.

“Now we can see our country is very friendly,” said Boris Kozikov of St. Petersburg, Russia. “This is very important for other countries around the world to see.”

And in a charming touch, Sochi organizers poked fun at themselves. In the center of the stadium, dancers in shimmering silver costumes formed themselves into four rings and a clump. That was a wink to a globally noticed technical glitch in the Feb. 7 opening ceremony, when one of the five Olympic rings in a wintry opening scene failed to open. The rings were supposed to join together and erupt in fireworks.

This time, it worked: As Putin watched from the stands, the dancers in the clump waited a few seconds and then formed a ring of their own, making five, drawing laughs from the crowd.

Raucous spectators chanted “Ro-ssi-ya! Ro-ssi-ya!” – “Russia! Russia!” They got their own Olympic keepsakes – medals of plastic with embedded lights that flashed in unison, creating pulsating waves of color across the stadium.

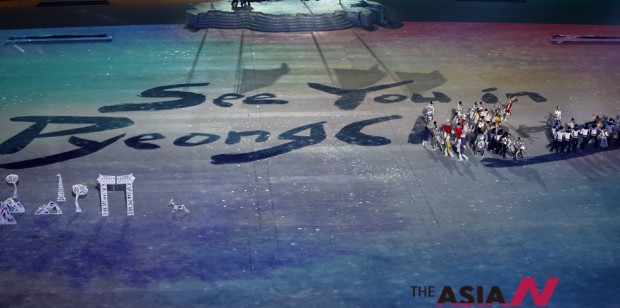

Athletes said goodbye to rivals-turned-friends from far off places, savoring their achievements or lamenting what might have been – and, for some, looking ahead to 2018. The city where they will compete, Pyeongchang, offered in its segment of the show a teaser of what to expect in four years with video of venues, Korean music and delightful dancers in glowing bird suits.

Winners of Russia’s record 13 gold medals marched into the stadium carrying the country’s white, blue and red flag. With a 3-0 victory over Sweden in the men’s hockey final Sunday, Canada claimed the last gold from the 98 medal events.

Absent were six competitors caught by what was the most extensive anti-doping program in Winter Olympic history, with the IOC conducting a record 2,631 tests – nearly 200 more than originally planned.

Russia’s leader had reason to be pleased as the Olympics dubbed the “Putin Games” ended. His nation’s athletes topped the Sochi medals table, both in golds and total – 33. That represented a stunning turnaround from the 2010 Vancouver Games. There, a meager three golds and 15 total for Russia seemed proof of its gradual decline as a winter sports power since Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Russia’s bag of Sochi gold was the biggest-ever haul by a non-Soviet team.

Russia’s last gold came Sunday in four-man bobsled. The games’ signature moment for home fans was Adelina Sotnikova, cool as ice at 17, becoming Russia’s first gold medalist in women’s Olympic figure skating.

Not every headline out of Sochi was about sport. Going in, organizers faced criticism about Russia’s strict policies toward gays, though once they started sliding and skiing and skating, most every athlete chose not to use the Olympic spotlight to campaign for the cause. An activist musical group and movement, Pussy Riot, appeared in public and was horsewhipped by Cossack militiamen, drawing international scrutiny.

And during the last days of competition, Sochi competed for attention with violence in Ukraine, Russia’s neighbor and considered a vital sphere of influence by the Kremlin.

Bach singled out Ukraine’s victory in women’s biathlon relay as “really an emotional moment” of the games, praising Ukrainian athletes for staying to compete despite the scores dead in protests back home.

“Mourning on the one hand, but knowing what really is going on in your country, seeing your capital burning, and feeling this responsibility, and then winning the gold medal,” he said, “this really stands out for me.”