China’s conditions to accept a ‘unified Korea’

Recent months have seen an unusual amount of noise and a sense of crisis in Northeast Asia, a region in which nationalist passions have not run this high for decades. Sino-Japanese relations have hit a nadir, while US commitments to Japan have been strongly confirmed.

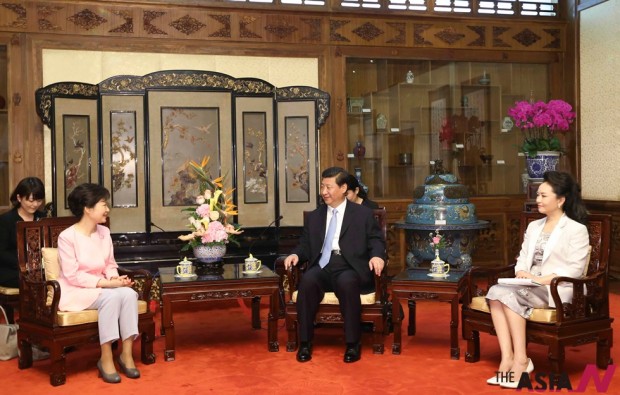

While South Korea’s President Park Geun-hye comes from the political right and therefore has impeccable pro-American credentials, her actual policy seems to indicate that Seoul would like to have better relations with China – at the expense of its relations with Japan, if necessary. It also appears that South Korea wishes to stay out of disputes between its ally the United States and China as much as possible.

This is quite understandable: it is Seoul who is likely to get it in the neck if relations between Washington and Beijing take a turn for the worse. What is of especial importance in all of this though, is the role that China may play if a crisis erupts north of the DMZ.

To be frank, there is little doubt that there is only one likely scenario for unification: that of Germany. A domestic crisis in North Korea, followed by the collapse of the Kim dynasty remains a distinct possibility. Of course, no one knows when it will happen – and whether it will happen at all, but the recent developments in Pyongyang make many observers wonder how stable the North Korean regime really is.

If the government in Pyongyang disintegrates, the likely outcome is the absorption of the North by the South. Such a possibility can only be actualized so long as the Heavenly Kingdom remains neutral; if Beijing decides to intervene and create a puppet entity in the North, South Korea can do little but grin and bear what is imposed on their northern neighbors.

It is therefore important for Seoul to ameliorate Chinese fears about a unified Korea – such fears are indeed widespread in Chinese foreign policy circles, as the present author has confirmed in talks with his Chinese colleagues.

Right now, most of my Chinese contacts, while not ruling out the possibility of regime implosion in North Korea, do not see such a scenario as highly likely (at least for the next few years). I have frequently heard that there is widespread dissatisfaction with the government inside North Korea, but I was frequently assured that in the absence of organized opposition, such dissatisfaction is unlikely to translate into political activities.

In case of N. Korean regime collapse

This might indeed be the case, but I am not sure, neither are the Chinese. Therefore, they are discussing the possibility of regime collapse in the North and what is to be done in such an eventuality.

It appears that such discussions have yet to produce a consensus amongst Chinese analysts and diplomats. Indeed, the issue of Korean unification is frequently seen through the lenses of steadily worsening Sino-US relations. I have been told a number of times that a unilateral American intervention in North Korea, especially if it is done without prior warning, is not acceptable to the Chinese side.

If this were to happen, China would retaliate, either by indirectly supporting what will be left of the North Korean regime (arms shipments, financial transfers and the like), or by establishing direct control over North Korean territory adjacent to the Sino-North Korean border. Such a response is likely to lead to a potentially dangerous confrontation. We can only hope that Washington and Beijing will discuss matters before it is too late. There is some room for optimism, though: most Chinese analysts believe that a South Korean intervention in the North is acceptable to China (especially if the Chinese are informed ahead of time).

There is little doubt that the unification of Korea will have a generally negative impact on the geopolitical position of China. However, it seems that the emergence of a unified Korean state still might be acceptable to the Chinese side if certain conditions are met.

I have heard for many years from the Chinese about a set of conditions that will make Korean unification permissible for the Chinese government.

First, the Chinese stress that a unified North Korea should not become an ‘American aircraft carrier’ placed on China’s borders. For unification to be acceptable, the Chinese will expect the US presence on the Korean peninsula to be frozen or reduced. Most likely, they will accept an agreement by the United States not to place any forces north of the current DMZ, as well as an assurance that the United States will not increase its forces on the Korean peninsula. This is important because in Beijing, US forces in Korea are seen as a serious potential threat.

Second, the Chinese are likely to insist that the government of a unified Korean state accept (unequivocally) the existent Sino-Korean border. This is important because some Korean nationalists have laid rather wild claims to chunks of Northeast China. The talks about alleged “Korean historic rights over Manchuria” do not remain unnoticed in China.

Worsening Sino-US relations

Third, the government of China also would like to make sure that the post-unification government of Korea will honor the Sino-North Korean agreements pertaining to mining rights, port usage rights and other concessions. In recent years, the Chinese government concluded a number of such agreements with Pyongyang.

If such demands (in my humble opinion by no means excessive or irrational), China is likely to remain quiet in the case of a major crisis on the Korean peninsula.

The current situation is rather uncertain, though. Chinese decision makers continue to see North Korea as being part of its relations with the United States, though the denuclearization issue is taken more seriously than it used to be. Therefore, in order to alleviate Chinese worries, it is quite important for South Korea to demonstrate that it will not merely follow Washington automatically and uncritically.

The current South Korean line is seemingly moving Seoul somewhat closer to Beijing – even though the recent Chinese claims about the Air Defense Identification Zone (CADIZ) have made Seoul rather uneasy. Surprising though it may seem, Washington should also encourage such an equidistant line because it creates the conditions required to solve the perennial North Korean problem. Needless to say, such a solution is more advantageous to the United States than all the strategic gains that can be reaped by clinging to all the minor strategic benefits created by the current situation in Northeast Asia.