NK nuclear issue: No early solution

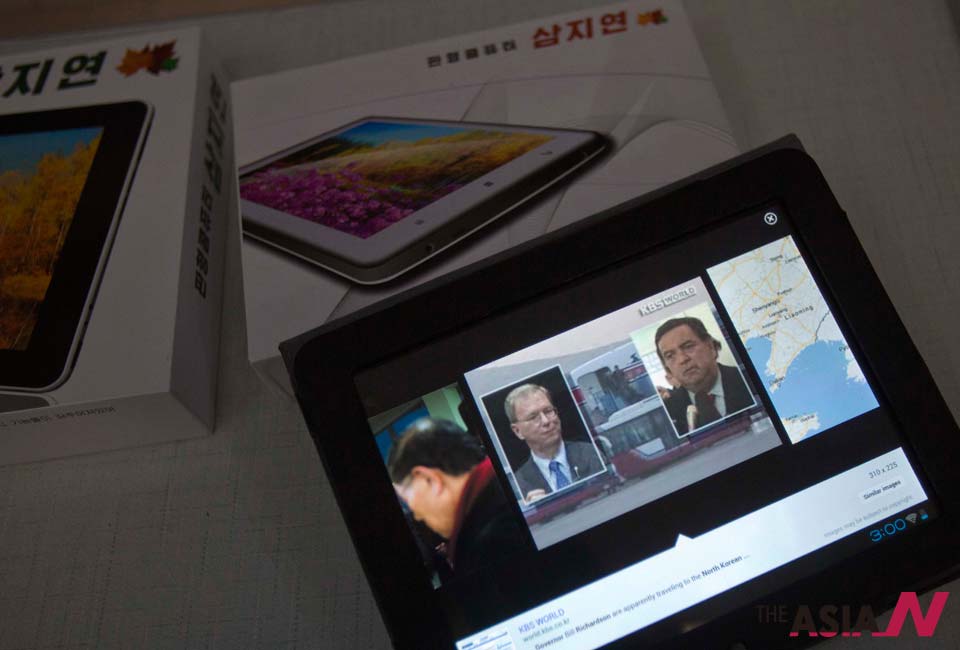

It seems that, after few months of hibernation, something is happening again in regard to the North Korean nuclear issue. The officials from the United States and North Korea met in Beijing Friday to discuss, citing a press report, a probability of restarting nuclear disarmament in return for aid.

We have heard this many times, have we? The first talks of this kind took place almost two decades ago. Since then North Korea has developed a working nuclear devise, produced between 30 and 50kg of weapon-grade plutonium and now is busy producing highly enriched uranium – all this against the background of almost continuous talks and negotiations.

This makes people skeptical – and increasingly so. People wonder whether the North Korean nuclear issue have a solution? Well, it largely depends on what you mean by the word ‘solution’.

On one hand, one might choose to follow the official position of the US government which holds that the only acceptable solution is “verifiable and irreversible dismantlement of North Korea’s nuclear program”. If this is how we define the ‘solution’, we should not be optimistic about the likelihood of its implementation. The North Korean regime does not have any reason to surrender its nuclear program (and a lot of reasons to keep it). In the long run, nuclear weapons could be surrendered by a new, post-Kim North Korean regime, but it might take decades for such a government to emerge.

Indeed, the North Korean regime has virtually nothing to gain from the proposed denuclearization. It needs its nuclear weapons for two main reasons – for deterrence and diplomatic leverage.

Deterrence is an important goal for North Korea’s leaders, who see themselves as being encircled and threated by the outside world. We should not be too quick to reject these fears are mere paranoia. We have seen recently how Washington used military force to replace governments not to its liking – and there is little doubt that Kim Jong Il is even less popular in Washington than Saddam Hussein.

Recent events in Libya have merely confirmed long-standing North Korean suspicions. A decade ago, Colonel Gaddafi did exactly what North Korean leaders are now asked to do – he surrendered his nuclear weapons program in exchange for economic cooperation. The deal backfired and Gaddafi would pay for his mistake with his life.

North Korea’s decision makers will have seen what happened to Gaddafi as another confirmation of their own correctness when it comes to the nuclear issue. They believe that as long as they have nuclear weapons, no foreign power will ever attack them. They also believe that as a nuclear state, they can do whatever necessary to suppress internal dissent or even rebellion, without the risk of falling victim to another ‘humanitarian intervention’.

Important as a deterrent nuclear weapons might be, they are even more useful as a tool of diplomatic blackmail. Objectively speaking, North Korea is a tiny country, whose population and economy is roughly equal to that of Ghana or Mozambique. It is also stuck with an outdated and inefficient economic system it cannot reform. Therefore, in order to stay afloat, North Korea will have to attract foreign aid. This aid ideally should be generous and unconditional – in other words, donors should not ask too many questions about its distribution.

The major tool the North Korean government can use to extract such aid is its nuclear program. In order to receive aid payments, the North Korean rulers have no choice but to appear dangerous and unpredictable, so that the outside world would give them what they want, lest they cause even more trouble. This policy has worked for at least two decades and is likely to succeed in the future as well. But, the existence of the nuclear issue is the basic condition which makes such blackmail diplomacy successful. Without nuclear weapons, North Korea would immediately become a ‘Turkmenistan without gas’. This not a nice position for a regime whose stability depends upon the regular influx of foreign aid.

Therefore, nuclear negotiations have long become reminiscent of a soap opera, with recurrent topics, predictable twists of the plot and all-too-well-known protagonists. It is likely that, sooner or later, the Six-party talks will resume. Actually, this is good news since the Six-party talks help to keep tensions down and also serve a number of laudable purposes. That said, however, one has to be naive to expect that North Korea can be persuaded or bribed into surrendering their nuclear weapons.

At the same time though, this does not mean that the North Korean nuclear program cannot be managed or even ‘solved’, if one redefines the meaning of the word ‘solution’. North Korean leaders will never accept denuclearization, but they seem to be willing to talk about the freezing of their nuclear program. In other words, they will not talk about unilateral nuclear disarmament but they might be happy to talk about unilateral nuclear arms restrictions.

Indeed, even under the best imaginable conditions, North Korean scientists cannot outproduce Los Alamos. By now they have produced 5-10 crude nuclear devices; if they increase the number of these devices to 50 or even 100, their diplomatic leverage will not increase tenfold – actually, it will probably not increase at all. North Koreans might therefore agree to freeze their nuclear program if, in exchange, they will receive generous and regular payments from the international community.

Concurrently, they will expect that the existent nuclear devices will be tolerated. For them this will mean that protection against foreign invasion (or foreign support for a local insurgency) will be guaranteed and that they can continue to engage in diplomatic blackmail, when need be.

At present, this idea seems to be a non-starter in Washington and Seoul. There are good reasons for such apparent lack of enthusiasm. Indeed, such a compromise deal would indeed amount to rewarding blackmail. North Korea is the world’s only country to have walked away from the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), and subsequently developed nuclear weapons. Merely accepting it as a nuclear power, let alone providing it with rewards for such behavior, would create a dangerous precedent. The opposition to such a compromise is therefore likely to be large.

All these arguments are reasonable and a possible compromise with the North is indeed fraught with problems. However, in the world of politics one often has to make not a choice between good and bad, but rather between bad and disastrous. Unfortunately, one cannot find positive alternatives to the conditional acceptance of North Korea as a nuclear state.

Without such a compromise, North Korea will continue to develop its nuclear program. Sooner or later, the North will produce enough enriched uranium to compliment their earlier plutonium program – and uranium-based weapons are much more difficult to control in terms of proliferation. Furthermore, the North Korean engineers will eventually weaponize the nuclear devices and due time they may even be able to develop a long-range missile delivery system, which will be capable of delivering a nuclear-armed warhead to the US (or, for that matter, many other countries).

They are also likely to start military provocations – among other reasons, just to remind the world that they should not be neglected.

So it seems to be likely that, sooner or later, decision makers in the United States and elsewhere will realize that a frozen North Korean nuclear program is clearly a lesser evil compared to a steadily growing North Korean nuclear program, combined with proliferation activities. This realization is not going to happen any time soon, of course. Quite likely it will take another nuclear test or a successful missile launch or a couple of proliferation attempts before US politicians realize that occasionally it might indeed be a lesser evil to reward a blackmailer.

Of course, the compromise solution is imperfect. As soon as this deal is made, the North will try to cheat, as they always do. It goes without say that such a compromise will only work so long as the US government is willing to pay.

Nonetheless, if North Korea continues to exist for another decade or so though (this is not unlikely), such a patently imperfect deal will have to at least be considered seriously. This is a bad idea, to be sure, but the alternative is worse.

One thought on “NK nuclear issue: No early solution”

“In the long run, nuclear weapons could be surrendered by a new, post-Kim North Korean regime, but it might take decades for such a government to emerge.”

– Post-Kim North Korea is nonsense. DPRK exists only to maintain the Kims’ dynasty and the surrounding elites alive and happy. Once the “revolutionary bloodline” of Kims is interrupted the country will plunge into chaos the only exit from which will be unification with the South. Peaceful co-existence of North and South Korea cannot be lengthy for economic reasons. Surely, the post-Kim North Korea won’t last long.