Russia’s interests on the Korean Peninsula

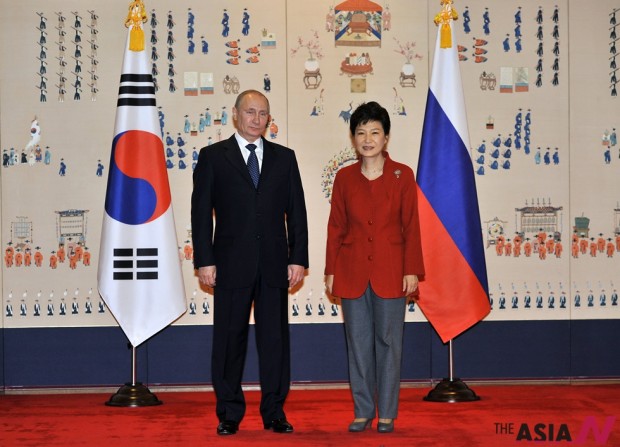

The summit between South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Russian President Vladimir Putin has attracted much attention to Russia’s attitude toward the problems of the Korean peninsula.

When it comes to Russia’s attitude to South Korea, there is surprisingly little to discuss. In spite of some misunderstandings and minor frictions, relations between Moscow and Seoul are devoid of intrigue. Both sides’ main interest is economic and these relations are mutually complimentary: South Korea needs Russian raw materials and technology, while Russia has a large appetite for the consumer goods coming from the Land of the Morning Calm. On top of that, there is a modest but respectable level of interpersonal and tourist exchanges, as well as flourishing cultural interactions between the two countries.

Things are rather different when it comes to North Korea. While Russia’s relations with South Korea are principally economic, such considerations are for all intents and purposes absent from its relations with North Korea.

Though this is not widely understood in the south of the DMZ, Russo-North Korean trade is essentially absent. To put things in perspective, in 2012 the volume of Sino-North Korean trade hit $6.1 billion, having increased nearly 10-fold over the last decade. Meanwhile, Russian trade with North Korea remained a paltry $90 million, and has been stagnant since the late 1990s. In other words, Russo-North Korean trade is now some 60 times less of Sino-North Korean trade.

It is also important to remember that while, over the last decade, the total North Korean foreign trade was increasing, its trade with Russia actually declined somewhat. Occasionally, in the list of North Korea’s trade partners, Russia ranked alongside the Netherlands and Thailand. Indeed, a trade volume of around $100 million means that the two countries are not engaged in any meaningful economic interaction.

Russo-N. Korean trade in decline

One should not be overly surprised about this fact: the economies of Russia and North Korea are not in the least bit complimentary in their structure. North Korea has nothing of much interest to Russian businesses, and has no money to pay for what Russia can sell it. At present, North Korea has a certain amount of competitive advantage in three areas – mineral resources, fishing and cheap labour. None of these areas are however of much interest to Russian businesspersons.

Mineral resources constitute a considerable and fast growing part of North Korean exports. However, Russia, with all the riches of Siberia at its disposal, is not all that interested. Some Russian companies have indeed been approached by North Korean government agencies, which sought Russian investment in North Korean mining (obviously such an investment is seen as politically desirable, in order to counteract China’s growing dominance). Russian companies were not impressed by what they saw in the North: the mines in question were in very bad shape, and lacked even basic infrastructure. The quality of the deposits themselves also left much to be desired. So Russian business decided that the projects would not be worth the efforts required, especially given the volatile political situation in the region.

Seafood is also of limited interest for Russian business. North Korean fishermen happily sell their catch to the Chinese, whose appetite for seafood is well known. In some cases, seafood ends up being resold to South Korea and Japan (two other countries also well known for their legendary appetite for such delicacies). Russians, however have never been known for their appetite for fish, let alone sea cucumbers or whelks. On top of that, Russia has a large and efficient fishing fleet, which is quite capable in satisfying the moderate domestic demand for fish.

Cheap labour might be of some limited interest to Russian business, especially when they have the opportunity to use North Korean workers on construction sites in Russia proper. However, Russian businesspersons – unlike their Chinese colleagues – are not in the slightest bit interested in building factories within North Korea proper. Chinese and even South Korean companies have begun to seriously consider outsourcing their production to the North (it is after all a country where $35-40 is considered to be a good salary). Russia’s economic model does not require cheap factory labour, and therefore the demand is quite limited. There are some 10,000 North Korean workers employed in Russia at present, but this number is unlikely to increase significantly.

Recently, great expectations were pinned upon the construction of a trans-Korean railway and gas pipeline. These projects are often described as being possible cases of cooperation between Russia and North Korea. In actual fact, though, both projects will have little impact on North Korea’s actual economy; rather, the projects are designed to traverse North Korea for the minimum cost, while providing Russian business with faster and cheaper access to lucrative South Korean and Japanese markets. If constructed, neither project will have much to do with the actual North Korean economy.

Barely from an economic motive

Indeed, had North Korea been an uninhabited desert or jungle the differences would not be that large economically. It appears unlikely at the present time that these projects will ever see the light of day. The putative trans-Korean railway project has been in the offing for some fifteen years. At the time when it was first proposed, in the late 1990s, there was no shortage of government declarations as to the project’s economic benefits. There has yet to any work though on this project.

Russia’s recent construction of a railway between Hasan (the railway station on the Russo-North Korean border) and the North Korean port of Rason has been seen by many as the first stage of the creation of the trans-Korean railway. However, this is not the case, since this short, some 54 km long, railway link connects the port of Rason – partially leased by the Russians – with the Russian railway system, thus making the port facilities accessible to Russian businesses. It would be built anyway, and has little if any connection with the trans-Korean railway plan.

The fact that either pipeline or railways projects have begun so far is not surprising. A trans-Korean railway is likely to be very expensive: costs running into the billions of US dollars (the current estimate is $3.5 billion). Russia’s state railway company is not particularly interested in investing such a colossal amount of money into such a politically unstable area. Any crisis on the Korean peninsula may interrupt construction or stop the operations of the finished railway. If this were to happen, already invested resources will be lost, and nobody will compensate the company for such losses.

The same is applicable to the much discussed natural gas pipeline project. A pipeline is as expensive to construct as a railway, and its construction and operation is similarly premised upon relative political stability. Unfortunately, the Korean peninsula is not known for such stability, and it is therefore not surprising that Russian business is very skeptical about such a project. They show interest, but they are in no hurry to start the actual digging.

Thus, unlike relations between Russia and South Korea, relations between Moscow and Pyongyang are driven not by economics but by geopolitics. Russia wants a stable Korean peninsula, and it also does not want the influence of the United States or China to increase markedly. This is the reason behind Russia’s willingness to be relatively active in dealing with the North. However, such diplomatic efforts have virtually no economic motive.