Clash of values over Bukit Brown, Singapore’s ‘Angkor’

In 1860, the jungles of Cambodia yielded a hidden secret when French naturalist Henri Mouhot stumbled upon the ruins of Angkor Thom. Intriguing wall figures and building architecture had led him to the long-lost Bagon at Kampong Thom in the deep forests of the Tonle Sap Lake, of whose grandeur and legend farmers, and monks had long whispered about. Mouhot was to be followed in 1866 by a French archaeological expedition that marked the beginning of restoration and preservation of Angkor Wat.

Singapore experienced its Angkor moment when the hills in its central catchment area were re-discovered to be hosting 100,000 historic tombs and artifacts dating back to the era of Chinese Diaspora – the migration and settlement in South-east Asia, then known as Nanyang (South Seas). Covering an area of 200 acres, Bukit Brown Cemetery is on record as the largest Chinese burial site outside of China, but put on fallow in 1975.

What resonated with many Singaporeans were the tombstones of pioneers, for whom roads, hospitals and schools have been named after. One of them was the great grandson of philanthropist Tan Tock Seng, honoured with a hospital in his name. Tan Boon Liat, who died in the 1930s, had a headstone distinguished by its “12 rays of sunlight, showing his longtime association with Sun Yat Sen’s Kuomintang whose logo is a white sun with twelve rays on a blue background.”

What has also seized many young Singaporeans’ imagination is the light shed on the Singapore connection to the 1911 revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty in China. History had it that chiefs of clan associations and officials of chambers of commerce hosted Sun Yat Sen’s eighth visit to Singapore to raise funds for his revolutionary cause, and also for full measure of rival Kang Yu Wei’s reforms.

“Few would know that 20 members of the Tong Meng Hui (Chinese Revolutionary Alliance) members who supported Dr. Sun Yat Sun and 15 members of the early Chinese Republic Party formed at that time is actually at Bukit Brown,” said amateur historian Raymond Goh in his blog.

“More than a century of transition of power and change in China can be reflected in the tombstones of Bukit Brown, from the Qing dynasties of (Emperors) Daoguang, Xianfeng, Tongzhi, Guangxu, Xuantong, the period where great changes take place like the Taiping rebellion, the remnants of the Qing dynasty after the Republic is formed, the Mingguo Years, followed by the Japanese conquest of Koki Years, Syonan Years.”

Chinese diaspora tomb relics

History aside, Bukit Brown is prized for its potential as an outdoor natural museum where visitors can learn about Chinese and Peranakan burial rites, geomancy practices and mythical deities as well as the unique craftsmanship of tomb artefacts and construction materials.

A case in study is the iconic bow-shaped tomb of comprador Ong Sam Leong, sited on a hill facing south in line with Feng Shui principles, allowing rain water to flow downwards and be channeled via the spouts of fish statuettes into the surrounding moat. It is adorned with panels of carvings depicting Chinese filial piety lores and on opposite sides with a pair of lion statues and two uniformed Sepoy guards holding rifles on each side.

In the eyes of ardent advocates, this historic heritage and cultural place is good enough to be a United Nations-recognised world heritage site. However, the authorities are not seeking such global honour.

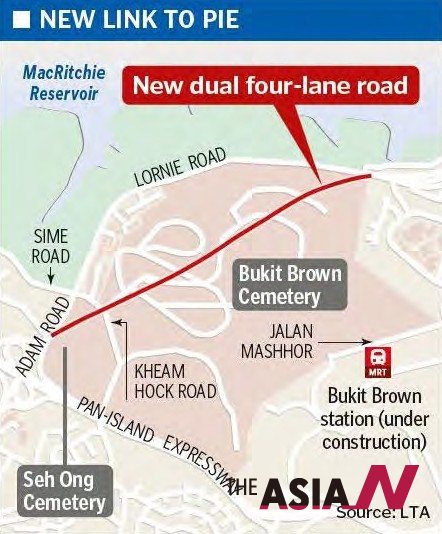

Instead the Land Transport Authority (LTA) is pushing ahead with plans, first announced in 2011, to put an eight-lane carriage-way through Bukit Brown. More than 4,000 graves will be exhumed later this year for the 2 km highway to help ease peak-hour congestion on two adjoining roads. Smooth-flowing traffic is seen here as vital for the economy.

The inroads into Bukit Brown were to dash the heritage and nature groups’ hopes in its representations to the government to keep the cemetery intact as a national heritage park.

A Singapore Heritage Society spokesman Dr Chua Ai Lin described the government’s move as “a missed opportunity for us to prevent irreversible impact on the environment and heritage.”

However, the LTA did make a concession: it will throw a 600m-long bridge instead of laying a road flat across the valley of the cemetery. This is to enable wildlife to cross below the expressway that will be up in 2017.

Even so, the Save Bukit Brown lobby groups have expressed regret that the government had not tried hard enough to look for viable alternative solutions to deal with the traffic problem.

Nor do they believe the authorities had given due and serious regard for their grounds of appeal from history, culture and war for keeping Bukit Brown intact. Military historians are trying to figure out Bukit Brown’s international dimension as a war cemetery.

“Thousands of unidentified bodies were buried in communal trenches which so far lay undiscovered. World War II battles were also fought on the hills of Bukit Brown,” said Raymond Goh of the Brownies as volunteer guides of the cemetery are known.

Collaborating this account, British archaeologist Jon Cooper, had given a specific account of a “Dante’s Inferno” battle at the hills of Bukit Brown on the evening of 14 Feb 1942 where British and local forces engaged invading Japanese troops. Singapore fell to the Japanese the following day. Cooper is working on the Adam Park Project to retrace the battles and find the resting places of the fallen soldiers. Adam Park is located near the cemetery.

Ecologically, the Nature Society of Singapore (NSS) hails Bukit Brown’s global significance as a carbon sink. “Together with the other large patches of wooded areas, it contributes to the sequestration of carbon in Singapore,” said Dr. Ho Hua Chew, chairman of the NSS conservation panel.

He pointed out that the city-state’s eco footprint of consumption person is 5.34 global hectares, higher than that of Germany (5.08), UK (4.89), South Korea (4.87), and Japan (4.73) according to a study on 153 countries by the Global Footprint Network.

Domestically, Bukit Brown acts as a rainfall sponge that would help prevent or reduce flooding of the city. In 2010, the popular Orchard road shopping belt was hit by flash floods that were attributed to unseasonal heavy downpour and the drainage canals’ inability to channel run-off water to the seas, a situation made worse by the highly built-up environment.

Incidentally, the island-state is also concerned with how potential rise in sea-levels from global warming will affect its beachfronts and has been studying the Dutch dyke systems as a preventive measure.

But alas, all the cogent arguments for preserving Bukit Brown have run smack into the hard reality of a 714.3 sq m (275.8 sq miles) metropolis that is set to upsize its current population of 5.46 million.

Historically, development priorities have always trumped nature and heritage concerns. As many as 21 cemeteries had been cleared, and 120,000 graves since 1975 had been exhumed by the state for housing and roads.

The high hopes for Bukit Brown, including its potential listing as a UNESCO World Heritage site, have been dampened, if not dashed. The integrity of this “mausoleum” may be breached by the expressway across its flank. But the larger threat of plans to turn the sprawling graveyard into housing estates would only materialise in 10 to 20 years. So the heart of Bukit Brown will still be there for now.

Tradition vs. modernity

Turning the burial site into a public park would fulfill such aspirations, said botanist Wee Yeow Chin, a past NSS president who recalled making a night visit there to study nocturnal birds. Indeed, 90 resident and migrant species have been spotted in Bukit Brown, making up one-quarter of the total bird species recorded in Singapore.

Bukit Brown is no Angkor Wat by any stretch of the imagination. As such, its fortune has taken a different turn. And its fate may be sealed. Even so, the mother of all cemeteries will always remain in the hearts and minds of the many who seek to keep it as a national treasure. Already, it has kindled in Singaporeans a keen awareness of a misty but nevertheless rich and proud era to which they seek to connect and relate. A final choice will be made reflecting an ongoing clash of values: between development/modernity and conservation/tradition.

“The decision we as a society make about the future of Bukit Brown will reflect the values we place on our roots, our collective identity and the sense of belonging we wish to inculcate in future generations of an increasingly globalised Singapore,” said the Heritage Society.