Muslim Brothers: No End Game!

The story the Society of Muslim Brothers is related to the life and death of many people, but the most adequate start could be the story of its founder and supreme guide; Hassan AL-Banna (1906~1949).

Hassan AL-Banna was born in Mahmudiyya, a village near the northern Egyptian city of Alexandria, where he was trained as a teacher at Dar al-Ulum School. He taught principles of Islam in various cities, but especially Ismailia (another Egyptian city on the banks of Sues Canal). At first he followed the teachings of Muslim reformer Mohammed Rashid Rida, but later, in 1928 Hassan AL-Banna founded his own organization; the Society of Muslim Brothers.

At the beginning, Muslim Brothers was an association for religious teaching, but, with the removal of its headquarters from Ismailia to Cairo in 1932, it evolved into a political society aiming at the purification of Islam and calling for the transformation of Egypt into an Islamic state.

Hassan AL-Banna’s simple doctrine won widespread support among urban workers and some younger intellectuals, and his charisma won him sympathy among Muslims in many Arab countries. He founded a daily newspaper, al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun, to propagate his ideas, and he secretly ran candidates for the Chamber of Deputies.

After the United Nations voted to partition Palestine, the Muslim Brothers were among the leading advocates of open resistance, and they formed volunteer brigades to fight against the Zionists. As his society grew more radical and prone to terrorism, the government tried to suppress it by seizing its funds, closing its branches, and interning some of its leaders while Egypt was under martial law during the Palestine War. After Prime Minister Mahmud Fahmi al-Nuqrashi was assassinated in December 1948 by a student attached to the Brotherhood, Banna was murdered by government agents in February 1949.

There was some famous trial called the “Jeep Case”. It was the trial of Muslim Brothers who were Egyptian army officers. The incident takes its name from the discovery in November 1948 of an army jeep filled with papers that provided the first proof that the brothers had a secret apparatus using terrorism to undermine public order, giving the government grounds to dissolve the Society on 6 December 1948. The trial of the arrested brothers was delayed for two years; some of the evidence proved to be tainted, and half of the defendants were acquitted.

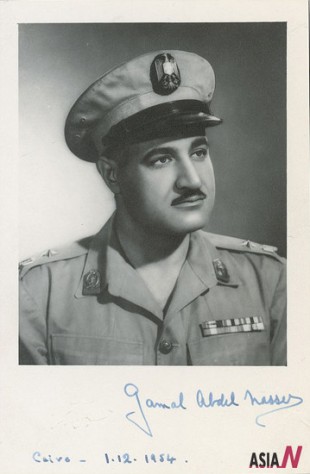

Muslim Brothers contained a secret wing, al-Jihaz al-Sirri, which was often accused of using terrorist methods against its enemies and of assassinating political leaders such as Nuqrashi in 1948. After Banna was killed by government agents in February 1949, Hasan al-Hudaybi was chosen to succeed him as supreme guide. Some Free Officers had ties with the Society, which remained influential just after the 1952 Revolution, but its support for Muhammad Najib in 1954 estranged it from Jamal Abd al-Nasir.

Several collections of Banna’s speeches and articles have been published, as have his memoirs, Mudhakkirat al-da’wa wa al-di’aya. A highly articulate speaker and writer, he was personally incorruptible in an era dominated by corrupt politicians, but his ideological rigidity blunted his political impact. One of his voices after death was AL-DA’WA (The Lights) weekly magazine of the Society of Muslim Brothers, edited by Hasan al-Ashmawi, from 1951 to 1954, when it was outlawed by Jamal Abd al-Nasir (then the minister of interior). After the Society was allowed to revive, it was edited by Umar al-Tilmisani from 1976 until Anwar al-Sadat banned it in September 1981.

Some historical moments are also related to, or connected with Muslim Brothers.The Black Saturday was one of them. It was the 26 January 1952 when riots of Egyptians burnt buildings in the heart of the Egyptian capital, especially those owned by Europeans or popularly associated with Western influence, in central Cairo, following the killing by British troops of 50 Egyptian auxiliary policemen in Ismailia a day earlier.

The heavy destruction of property and loss of European and Egyptian lives were widely construed at the time as evidence of the Egyptian government’s inability to maintain order. Consequently, King Faruq dismissed the Wafd Party government of Mustafa al-Nahhas and appointed a series of Palace cabinets that failed to restore public confidence in the monarchy, which was toppled by a military coup six months later. It has never been determined who started Black Saturday; popular theories at the time implicated the Society of Muslim Brothers or the Egyptian Socialist Party, formerly Misr al-Fatat.

Being in Cairo, Muslim Brothers involved themselves in every type of life. They even raised their objection against the fine arts, and cinema. Historically the motion picture shows in Egypt began in 1904, if not earlier, and cinema halls were erected in Alexandria and Cairo before World War I. The influx of British imperial troops during that war did much to introduce Egyptians to cinema productions from Europe and North America. Egyptian film production began in Alexandria in 1917. A full-length silent film, al-Bahr byidhaq leh (Why Does the Nile Laugh?) soon followed, and in 1925 serious efforts at film production began, leading to the appearance of four movies two years later. The first sound film, Awlad al-dhawat (Children of the Upper Class) was synchronized in Paris soon after the talking pictures began in the West. A large Arabic film company, Studio Misr, owned by Bank Misr, was founded in 1934. Cinema halls proliferated in the cities and towns of Egypt and the rest of the Arab world, to which Egyptian films were often exported. Egyptian films competed in the Venice Film Festival as early as 1936. Muslim Brothers and other conservative Muslims, notably al-Azhar, al-Shubban al-Muslimin tried hard to censor films, and that what the state did later for the sake of moral, political, and religious grounds.

When the Free Officers (Secret Egyptian army organization, led by Colonel Jamal Abd al-Nasir, that conspired successfully to overthrow King Faruq in July 1952) was formed, its members were aware of the influence of the Muslim Brothers, and that is why there were members to communicate with them to make sure of the success of the revolutionary movement. The founding members the Free Officers included Nasir, Hasan Ibrahim, Khalid Muhyi al-Din, Kamal al-Din Husayn, and Abd al-Mun’im Abd al-Rauf. They were joined later by Abd al-Latif Baghdadi, Anwar al-Sadat, Abd al-Hakim Amir, the brothers Jamal and Salah Salim, Husayn al-Shafi’i, and Zakariyya Muhyi al-Din. Their internal structure was pyramidal, with each officer responsible for developing cells within his own military unit. Many served as liaisons with other political groups: Khalid with Hadeto, Kamal al-Din Husayn and Abd al-Rauf with the Muslim Brothers, Sadat with Abdin Palace, and Nasir with several groups.

The 1952 Revolution led to the independence of lawyer’s association members, where many members of them were Muslim Brothers. Law was a “receding profession” under president Nasir, but president Anwar al-Sadat began admitting more lawyers to the cabinet, but later the lawyer’s association became a forum for opposition to his policies, including the peace treaty with Israel; he locked up half the members of its elected Bar Council in his September 1981 roundup. Under previous president Husni Mubarak, the Association resisted his regime’s efforts to curb its activities, and its often-reelected leader, Ahmad Khawaja, received much press coverage for his criticisms of government policies. A slate of Muslim Brothers was elected to its Council in 1992. They were ousted by the government in 1996 as part of its crackdown on Islamists. Elections scheduled for 2000 were cancelled by the government at the last minute, out of fear that the Muslim Brothers would win.

The Muslim Brothers secret wing’s attempt to kill president Nasir in November 1954 led to its suppression. Some of its leaders were put to death, and many served long prison terms at hard labor. Nasir briefly eased his persecution of the Society in 1964, only to revert to more arrests, trials, jail sentences, and executions, notably of Sayyid Qutb

Under the Emergency Law (1958) president Jamal Abd al-Nasir’s government, authorized the judicial system to detain suspects without charging them or guaranteeing them due process during an investigation. After 30 days, a detainee may petition the State Security Court to review the case. If the court orders the detainee’s release, the interior minister has 15 days to overrule the court, but the detainee may after 30 days petition again for release.

Even if the detainee is released, however, the interior minister may rearrest the suspect. The government has often used this law against Islamists, leftists suspected of political violence, drug smugglers, illegal currency dealers, and even striking workers, pro-Palestinian student demonstrators, and relatives of fugitives. As of 1990 the government admitted to holding 2,411 individuals, 813 of them on political charges. The estimated number of detainees in 2002 was 15 thousand, mainly members of the Jama’at or the Muslim Brothers. Although some civilian suspects are tried by the military courts, in most cases detainees have been released after interrogation and without trial. This law has been stopped last month only!

After paving the road in every aspect of life, whether in lawyer’s association, and many other associations, and after being given the chance to collect funds from the Islamist states in the Arabian Peninsula, the Muslim Brothers went into the game of elections. It seemed that they were able to and accept being allied with any other different political group! As elections in 1984 marked the first People’s Assembly elected under the 1983 law introducing proportional representation and during the presidency of Husni Mubarak, the New Wafd Party, allied with the outlawed Muslim Brothers, won 58 seats, against the 303 won by the ruling National Democratic Party. The assembly was dissolved in 1986.

The election in 1987 produced the largest number of deputies opposed to the ruling NDP. The Islamic Alliance, a coalition of the outlawed Muslim Brothers, Liberal Party, and Socialist Labor Party (SLP) won 60 seats, compared with 30 for the New Wafd Party and 390 for the NDP. This Parliament was ruled unconstitutional and was dissolved. In 2000 elections, and owing to the reports and suits filed by human rights organizations against the 1995 Elections, these elections took place under judicial supervision in the polling places. In some cases, however, police impeded the entrance of would-be voters.

The election occurred against a backdrop of issues over dual nationality, constraints imposed on opposition parties by the government, the contest for control of the New Wafd after the death of Fuad Siraj al-Din, and the high profile arrest of Sa’d al-Din Ibrahim. Fourteen legal political parties took part: the Arab Democratic Nasirist Party, the Green Party, the Liberal Party, the Misr Arab Socialist Party, Misr al-Fatat, the NDP, the NPUP, the New Wafd Party, the SLP, al-Takaful Party, al-Umma Party, the Unionist Democratic Party, al-Wasat (Islamist) Party, and al-Wifaq al-Qawmiyya Party.

The results of the three-stage elections showed the voters’ disaffection with both the ruling and opposition parties and their growing support for independent candidates. The ruling NDP lost 22 seats, some of which had been held by party leaders, and won 388. The New Wafd won 7 seats, the NPUP 6, the Arab Democratic Nasirists 2, and the Liberals 1. Seventeen seats were taken by independents who acknowledged support for the outlawed Muslim Brothers; 21 were won by actual independents.

Of the NDP’s 388 seats, 218 of the winners ran as independents, often opposing candidates selected by the NDP, but later joined the ruling party. Some analysts believe that the strong support shown for Muslim Brothers may lead to their legalization before the next election.

The new form of Muslim Brothers started with Quranic teaching at the Martyrs Mosque in Suez and the Nur Mosque in Cairo’s Abbasiyya district. The organization openly opposed Anwar al-Sadat’s peace policies in the 1970s and agitated strongly in 1985 for the immediate application of the Shari’a to Egypt. The government responded by putting all private (ahli) mosques under the awqaf ministry’s supervision, hoping to curb Islamism.

Another famous name to be connected with Muslim Brothers is Sayyid Qutb (1903–66). He was a thinker and writer. Born in Musha (near Asyut in Upper Egypt), the son of a respected farmer who belonged to the National Party, he was educated at his village kuttab, where he memorized the Quran by the age of 10; at a Cairo secondary school; and at Dar al-Ulum (the same school where the founder of Muslim Brothers studied), where he fell under the influence of the Egyptian writer Abbas Al-Aqqad and became interested in English literature. After graduating in 1934, he worked for al-Ahram newspaper, wrote literary articles for al-Risala and al-Thaqafa magazines, taught Arabic, and served as an education inspector in Qina (another city in Upper Egypt).

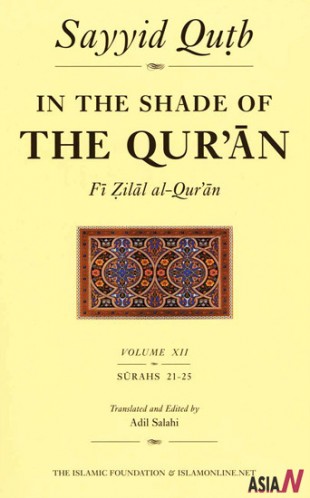

He was sent to study educational administration in the United States from 1948 to 1951, during which time he grew disenchanted with the West as he observed the moral corruption of American society, its racial prejudice, and its strong anti-Arab bias caused by the Palestine War. Upon returning, he criticized Egypt’s educational programs for their British influence and called for a more Islamic curriculum. He developed close ties to some of the Free Officers, notably Kamal al-Din Husayn, who wanted to make him education minister, and he served as the first secretary-general of the Liberation Rally. He resigned from the government in 1953 and joined the Muslim Brothers, taking charge of their instructional program and editing their newspaper. Imprisoned with the others after their failed attempt to assassinate Jamal Abd al-Nasir, he began writing books that were smuggled out of Egypt and published abroad, notably al-Adala al-ijtima’iyya fi al-Islam (translated into English as Social Justice in Islam), Fi zalal al-Quran (translated as In the Shade of the Quran), and Ma’alim fi al-tariq (Signposts along the Way).

Qutb became bitterly disillusioned with the Nasir government and argued that every person is an arena in the battle between godly and satanic forces. He called for a small community of good people to expel evil and establish righteousness in the world. Drawing on Quranic passages, he taught that Jews and Christians will always be implacably opposed to Islam and that Muslims must be prepared to combat Zionism, “Crusaderism,” and Communism to protect their community and its values.

His 30-volume interpretation of the Quran has become a standard reference work in mosques and homes throughout the Muslim world. Released in 1964, he was imprisoned again in 1965 and vilified by the press before being hanged for treason in August 1966. Since his death his ideas have inspired many Muslim individuals and groups, notably al-Takfir wa al-Hijra, Muslim Brothers and al-Jama’a al-Islamiyya in Egypt and abroad.

The third – and final – name to conclude shaping the history of Muslim Brothers is Umar Al-Tilmisany (1904–86) who had been the Supreme guide of the revived Society of Muslim Brothers and editor of its weekly magazine, al-Da’wa.

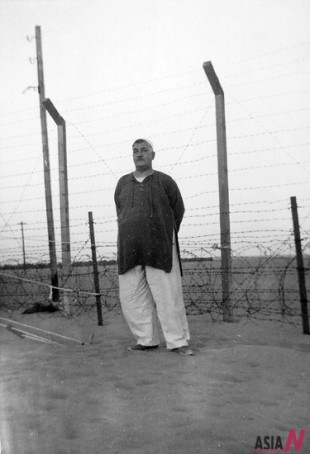

A graduate of the government Law School in 1931, he joined the Muslim Brothers Society two years later. He was one of the Brothers jailed following the abortive assassination attempt on Jamal Abd al-Nasir in 1954, serving a 15-year term. Tilmisani began publishing al-Da’wa in 1976; in it he inveighed against secularism and the power of the Jews, even ascribing Atatürk’s reforms to his alleged Jewish background, and the “Crusaders,” alluding to both the predominantly Christian West and Egypt’s Copts. He blamed the riots in al-Zawiya al-Hamra on a “Crusader conspiracy” against Islam. He was one of the 1,600 political and religious leaders whom Anwar al-Sadat jailed in September 1981, but Husni Mubarak later freed him. Tilmisani called for the gradual application of the Shari’a to Egypt’s laws, but opposed violence and terrorism. He wrote Dhikrayat la mudhakkirat (Recollections, not Memoirs).

Al-Banna, Qutb, and Umar Al-Tilmisany have shaped the history of the Muslim Brothers Society with their writings, but the new ‘leadership” of the Society are currently depending on those who have spent most of their lives in the States of Oil (An expression to describe the Arab Gulf States), and that is the reason why their calls and voices are more related to the fanatic Islam teachings, not the tolerant ones that have been the image of Islam in Egypt for 14 centuries.