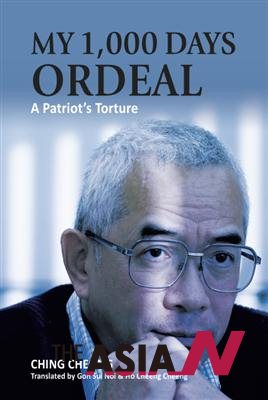

‘Uncrowned king’ throws book back at China’s judicial system

He might be hailed an “uncrowned king” in media circles but the Chinese authorities had him by their book. Hong Kong correspondent Ching Cheong, whose perspectives are greatly influenced by the Chinese traditional portrayal of a journalist, found himself labeled a spy by the Communist government in Beijing.

He was convicted in 2005 of leaking state secrets to Taiwan – deemed by the mainland as a renegade province for its aspirations for independence – after a closed-door trial and sentenced to five years imprisonment.

That is now history. The story of the trial and tribulations of the 63-year-old China watcher, who was released after serving half his term in 2008, is related in his book, My 1,000 Days Ordeal – A Patriot’s Torture. Ching Cheong said he wanted “to bring attention to China’s judicial system, so that we can together build a country that respects and protects the rights of the people.” “Otherwise, my time in jail would have been in vain.”

Chinese prison ordeal

It is ironic for the self-proclaimed patriot who had made personal sacrifices in his desire to help publicise China’s modernisation reforms under Deng Xiaoping to be imprisoned. “In the 30 years from 1974 to 2004, I had used my pen continually to explore the path towards progress for my country,” he said.

In 1974, the graduate teacher took a pay cut to be a journalist for Wen Wei Po, a pro-Beijing newspaper in Hong Kong. As the paper’s correspondent in Beijing in 1980 and deputy chief editor in 1988, he enjoyed privilege access. He was often invited to state banquets and also covered the Chinese Communist Party leaders’ annual retreat at Beidaihe resort.

Ching Cheong was even touted a potential Hong Kong delegate to the National People’s Congress after the colony’s return to China in 1997 as a Special Administrative Region under the one-country, two-systems formula.

But things took a sour turn with the military crackdown on pro-democracy student demonstrations at Tiananmen on June 4, 1989. Wen Wei Po, which earlier had criticised the move, was ordered to change tack and backed the repression.

Ching Cheong resigned in protest from the paper. He shared the students’ democratic aspirations, having grown up in a democratic milieu in Hong Kong under British colonial administration.

His severing of ties with the Chinese Communist Party authorities was a fateful decision. The veteran newsman’s subsequent fall from grace was linked to his writing a monthly situational analysis for Taiwan’s Foundation for International Cross-straits Studies (FICS). The Chinese authorities had regarded FICS as a spy outfit and saw Ching Cheong’s work as supplying intelligence that they deemed state secrets.

They took him in when he travelled to the southern city of Shenzhen to see a manuscript of the late Chinese leader Zhao Ziyang’s memoirs. Zhao was deposed as party general secretary after losing out in a behind- the-scene power tussle over the handling of the Tiananmen Incident. Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and other party elders had felt he was soft on the pro-democracy student demonstrators.

Revisiting his traumatic days under solitary confinement, the detainee No. 5022 said he was almost driven to take his life.

“I suffered indescribable mental anguish that grew out of a deep sense of frustration, regret and loss. I was frustrated because my loyalty to China and my honesty had sold me out.”

While under investigation, Ching Cheong had written a 20,000-word statement detailing his writings for the Taiwanese think-tank and the fees he received. He candidly said if the Foundation for Cross-straits Studies was indeed a spy agency, then his work would be tantamount to spying and detrimental to China’s security.

He added, “Then I expressed my regrets and would be willing to accept legal responsibility for it.” This was seized upon by the court as a confession of crime. It was good enough for it to hand down a guilty verdict against the defendant.

Avoiding legal pitfalls

Ching Cheong’s case underscored a professional pitfall for journalists. China’s wide definition of “state secrets” shows that “this is the easiest way to incriminate a journalist,” he said. “(For) journalists are in the business of finding out information that may be sensitive, whether it is already in the public domain or not.”

Besides inadvertently crossing the information/ intelligence boundary, the Straits Times correspondent also said he mixed up his “reporter and political participant” roles.

For while stationed in Taipei, he had also through his writings engaged in bridging differences between China and Taiwan. In 1995, cross-straits relations were rocked by the then Taiwan president Lee Teng-hui’s visit to the United States. Beijing saw Washington’s approval of the visit as violating the one-China policy, infringing upon China’s sovereignty and detrimental to efforts for peaceful reunification.

There has been precedence, he noted, citing a study by Professor Lee Chin-chuan of the City University of Hong Kong, that showed that Chinese journalists were not contented to be “purely professionals.” Instead, “given that Chinese newspapers were closely inter-linked with politics, journalists sometimes went beyond their responsibilities as journalists. This was the difference between Chinese and Western journalists.”

The Ching Cheong saga also highlighted an instance of professional indiscretion: under pressure, a journalist might compromise his/her contacts. To show he had nothing to hide, he had instructed his secretary to bring his laptop from Hong Kong and handed it over to the investigators in Shenzhen.

“I had voluntarily handed over my laptop, forgetting the professional ethic of protecting my sources,” he said. This had earned him stiff criticism from the Hong Kong Journalists Association chairperson Mak Yin-ting.

Ching Cheong said he accepted the criticism, including the comment by the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club convener of press freedom Francis Moriarty that “the professional standards of journalists in Hong Kong were behind that of Western societies, leading to a lack of clarity of professional boundaries.”

A humbler but wiser Ching Cheong hopes journalists would not only cull lessons from his mistakes, but also know about their rights and deal with difficult situations professionally. A couplet he composed under detention reflects his comeback: a scholar serves his country with nothing, other than his pen and a fiery heart.

“Until my imprisonment, I had never felt its great force, especially when combined with a journalist’s conscience,” he said. True to the adage of the “uncrowned emperor” Ching Cheong has the last word.