Which comes first – democracy or economic development?

Myanmar’s momentous make-over efforts have raised a partisan poser: which comes first – democracy or economic development?

The complementary yet competitive approaches to change-making adopted by President Thein Sein and opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi have called into question their different priorities.

The military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party in power have said economic development must take precedence over political progress. But the opposition National League of Democracy led by Daw Suu Kyi wants to see democratic institutions in place to steer economic growth.

To be sure, both Thein Sein, a general-turned politician, and Daw Suu Kyi, daughter of independence leader General Aung San, want to turn the stagnant economy around. Officially, the poor nation is aiming for a 7.7 per cent growth this year. The Asian Development Bank forecast is 6.5 per cent. Both leaders have been urging the United States to remove political and economic sanctions imposed on the previous Ne Win military regime for its repressive rule.

On his latest tour of the United States, President Thein Sein had coupled a well-timed release of political detainees, with pledges of continuing reforms. In particular, he emphasised that economic growth would help nurture political liberalisation.

This foreign policy line of commitment to change is calculated largely to win international support for trade and investment according to Ms. Moe Thuzar, co-ordinator of Myanmar Studies Group at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) in Singapore.

In contrast, Daw Suu Kyi has been winning Western backing for her quasi-civilian government to move faster towards democratic norms of transparency and accountability. “I do not see their agenda as contradictory,” said Dr. Tin, a member of the Myanmar Studies Group. “Thein Sein is doing what he could for political reforms, but he is not likely to go the way of Western liberal democracy.”

However, there is baggage from the past: opposition MPs tend to see military as those who clamp down on democracy. As it is now, the constitution reserves 25 per cent of the seats in Parliament to the military. The Army-approved charter also disqualifies Daw Suu Kyi from contesting for the post of President in 2015 for having foreign-born children and not having stayed in Myanmar for 20 years.

“Thein Sein has said, ‘it is not up to me’ to amend the Charter,” said Dr. Tin. The Nobel Peace laureate’s riposte appears to be that “If you can’t do it, I will do it my way’,” he added.

A positive aspect of parliamentary performance, Ms. Thuzar said was that lawmakers from the government and opposition were able to debate some issues along policy rather than partisan lines. In particular, the floating of the national currency(Kyat) and freeing up of rules on foreign joint ventures have led to a big jump in foreign investments.

But jobs are still scarce, especially for the unskilled and semi-skilled, said Dr Tin. As many as 60,000 of senior civil service employees were also retired to make way for Army personnel, said Prof Robert Taylor, another member of the Myanmar Studies Group. While people may not be richer they are no longer fearful, politically speaking, said Dr Tin.

Indeed, the easing of censorship laws has emboldened journalists to test the limits of reporting government corruption. The Voice Daily, for example, had dared to expose alleged misuse of funds by several ministries. The government sued for defamation. The freedom to form trade unions had led to a spate of strikes by factory workers seeking higher wages and adjustment in cost of living allowances.

No democracy, no development

The outbreak of civilian protests stemmed from the belief that if people “demonstrate peacefully, the Army won’t touch you,” said Dr. Tin. Yet, the government ordered a crackdown on the demonstrators at a copper mine protest last November with police using smoke bombs laced with phosphorus, injuring more than 100 protesters, including monks. This episode sparked fears that the military would not hesitate to use violent means to remove any challenge to its business concerns.

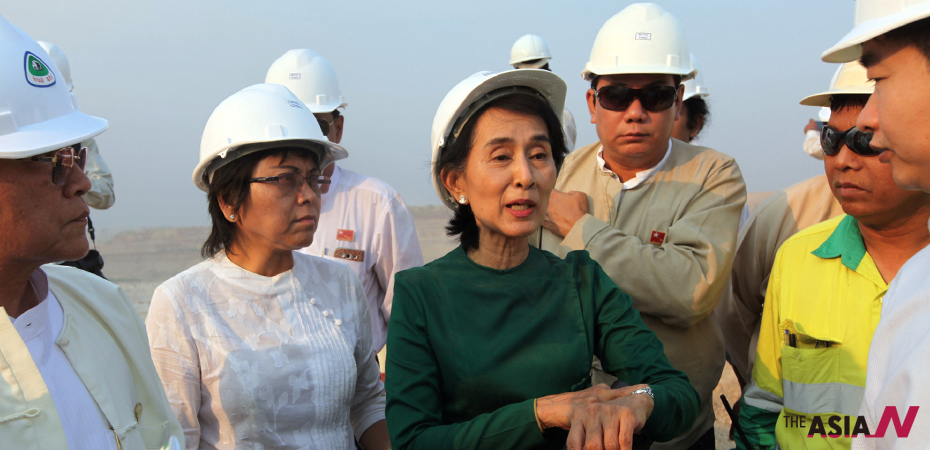

Fortunately, Daw Suu Kyi intervened in time to defuse the tension. She chaired a parliamentary commission that looked into the villagers’ grievances and the mine operators’ interests. It recommended return of some farm land, higher compensation for affected villagers and measures to protect the environment.

At the risk of alienating her supporters, Daw Suu Kyi also agreed to allow the mine to resume operations. This, she told villagers, was to honour a business deal and not send the wrong message to the outside world that Myanmar is welcoming foreign investments. She also had to take into account the general’s stake.

But the villagers and other protesters rejected her recommendations and wanted to stop the mine operations. “People have to restrain themselves. You just can’t go to the streets to air your grievances or resort to attacking your opponents. Instead, they need to develop habits…of accommodation.”

Daw Suu Kyi has shown what Ms.Thuzar called the “democratic frame of mind” to settle differences through dialogue and conciliation in her adroit handling of the copper mine dispute. “The country has reached a point where critical moves will make or break its efforts to find its place in the modern community of nations,” she said.

“If politicians messed things up, then the military will come back,” said Dr. Tin. Another red line not to be crossed is for the politicians to demand the Army to privatise their business enterprises.

Daw Suu Kyi’s arbitrating the copper mine dispute showed a sophisticated appreciation of such a risky scenario. More significantly, she has taken a new tack in pushing her political agenda that stays in tandem with economic demands of the moment.

In the new Myanmar, it does not really matter whether the chicken or the egg comes first. This is because in practice, one cannot do without the other.