N. Korea: player in the Gwangju Democratic Uprising?

Korean history as seen in South Korea is deeply contentious. It is not incidental that many school textbooks prefer to stop their narrative around 1960, quietly assuming that what happened after is too controversial for anything resembling an impartial judgment to emerge. Most of the prominent historical events and figures of the post-1945 period are deeply polarizing, so in modern Korea one person’s hero is almost certainly another person’s villain.

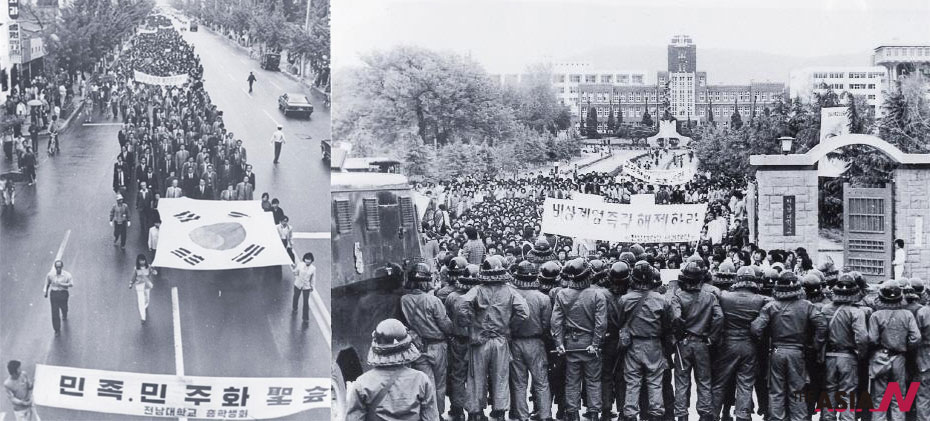

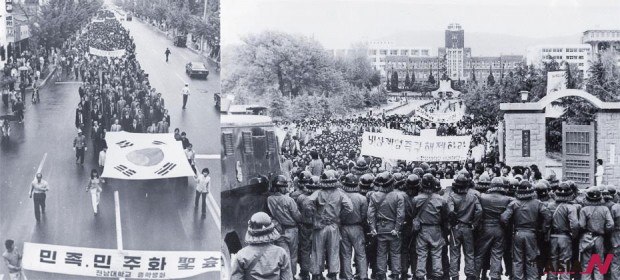

One of the events, which has been of little controversy up until now, was the Gwangju uprising of May 1980. Korean ‘progressives’ (this is how the Korean nationalist left likes to style itself) perceive this movement as a great expression of freedom and democracy directed against the then emerging military regime of General Chun Doo Hwan, and to some extent against his (alleged) American backers. A significant part of the right has come to agree with such an appraisal, and as a result only a relatively small faction of South Korea’s paleocons – often themselves former enthusiastic supporters of General Chun and his clique – have remained suspicious or hostile.

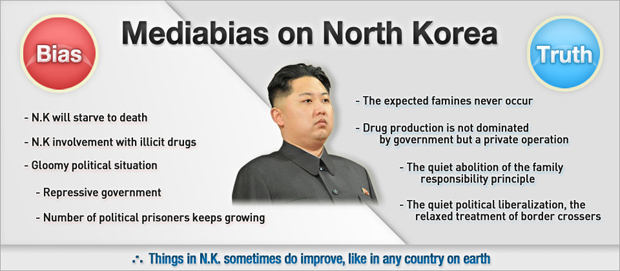

This seems to be changing though. In mid-May, two South Korean TV stations (both associated with right-wing media conglomerates, but quite respectable) aired what they said were sensational revelations. They insisted that new evidence indicates that a number of North Korean agents and Special Forces were secretly dispatched to Gwangju in 1980, whereupon they took part in the bloody street fighting between the pro-democracy revolutionaries and the forces of the new military dictatorship in Seoul. A recent defector from North Korea who claims to have been a Special Forces solider was interviewed by Channel A and TV Chosun – and said that he himself was on the special mission in Gwangju.

The immediate reaction of the South Korean left was a complete rejection of these claims, which were presented as a conspiracy by dictatorship-loving elements of the right to try to destroy the greatest and most tragic events in South Korea’s tortuous history on the road to democratization.

The left might actually turn out to be right. The evidence presented thus far does not appear to be all that persuasive, and it is not incidental that the channels received an official warning from the South Korean Broadcast Ethics Commission. Nevertheless, the left’s reaction is also rather unhelpful in a number of regards.

First, North Korean involvement with events in Gwangju cannot be ruled out – as we’ll see later. Second, even if North Korean forces were present, it does not change the meaning of the Gwangju movement. Regardless of whether a few dozen North Korean spies were present – or even fighting –on the streets of Gwangju, we cannot question the fact that the Gwangju uprising itself remains a seminal event in the history of South Korea’s democratic movement. Furthermore, the personal bravery and sacrifice of the people of Gwangju will not be undermined or forgotten by the fact that some North Korean spies happened to be in the city at the same time.

It would be helpful if South Korea’s leftist journalists were more careful in how they dealt with such accusations. The American experience is instructive: since the 1950s, the leftist intellectuals have vehemently denied all accusations of Soviet involvement with and support for the radical American left.

The partial opening of the Soviet archives in the 1990s, though, has substantiated many (but by no means all) of these accusations. Now we know that Alger Hiss, long presented as an innocent victim of a rightist conspiracy, was indeed on the KGB payroll (and worth every dollar spent on him). The Rosenbergs, the belief in whose innocence has long been an article of faith for every good American progressive, were indeed secretly working for the Soviets with great enthusiasm (but with few actual results).

But is this that significant? Soviet government was doing what all governments do, they were spying on other countries in order to learn as much about their political plans and technological advantages. Sometimes the Soviet agents managed to recruit people from the American left (or cooperate with them) – unsurprisingly, taking into account pro-Communist and even Stalinist sympathies of many American ‘progressives’ of the era. However, this fact does not make the witch hunt of Senator McCarthy less odious.

At the time, there is no doubt that the Gwangju uprising was welcome news in Pyongyang. North Korean leaders never made a secret of the fact that they wished to see South Korea’s military dictators overthrown by a popular rebellion. As a matter of fact, they also did not disguise their willingness to support anti-government movements in South Korea.

When, in 1960, the Syngman Rhee dictatorship was suddenly toppled in a popular uprising, the leadership of North Korea was shocked. Kim Il Sung stated that next time the South Koreans overthrow their leadership, the North should be ready to exploit political opportunities.

In the late 1960s, the North Korean government even sent Special Forces to organize a guerilla movement to launch a people’s insurrection against the South Korean state.

When the South Korean strongman Park Chung Hee was assassinated in October 1979, the pro-democracy movement in the South strengthened greatly, culminating in the Gwangju uprising. It seems all too logical to expect the North to have closely monitored the situation, and even tried to infiltrate the movement (and this is what we should expect of any government given the circumstances). All this does not mean that North Korean agents were necessarily present at Gwangju, but their presence is not implausible – regardless of what South Korea’s left-wing dailies now want their readers to believe.

However, the significance of these alleged revelations seems to be blown out of all proportions. Even if these accusations are proven to be correct, it should have no impact on our understanding of the Gwangju uprising. As every historian knows, there are indeed some very strange bed fellows in history, and in many cases independence and pro-democracy movements often receive significant assistance from forces of highly dubious repute.

It is worth remembering that Stalin’s Soviet Union was perhaps the most active and generous foreign supporter of the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. This support was motivated both by geopolitical considerations, but also by a desire to steer a future state in the direction of communism. Nonetheless, Soviet guns do not tarnish the reputation of the many democrats who lost their lives in the Spanish Civil War.

Similarly, Sun Yat-sen, the father of Chinese democracy, received support from a number of foreign powers – including, at times, Imperialist Japan, but no one would see him and his supporters as Japanese agents or even victims of evil Japanese manipulation.

As a matter of fact, the Japanese also provided support to a number of independence movements in Southeast and Southern Asia, but it would be completely dishonest to describe the emergence of independent Indonesia as a result of some Japanese machinations.

There are hundreds of such examples throughout history. Therefore, while there is a chance that the North Korean government did intervene in order to help the pro-democracy movement in South Korea, no sane person would use this fact (if it is indeed proven to be case) to argue that the pro-democracy movement was the result of North Korean intervention itself. The reports of North Korean involvement seem to imply that it is only thanks to a dastardly scheme on the part of the North Korean leaders that South Korea is today a democracy. Furthermore, the implication is that had the North Koreans left their Southern brothers alone, they would still be living very happily under the loving care of military dictators. Fortunately, both implications are deadly wrong.