NK’s effort to block defectors pays off

Where have all the NK refugees gone?

In late February, I was travelling in an area which should be frequently visited by any serious North Korean watcher – the parts of China in the vicinity of the North Korean border, the Yanbian autonomous region in particular.

In the past many people, including myself, visited the area in order to meet and interview the numerous North Korean refugees who were hiding there. While no exact estimates are available, it is widely believed that around 1999 the number of North Korean illegal migrants in the area peaked at 150,000-200,000. When I was in the area about four years ago, refugees had become relatively few in number, and as of today it is now possible to say that for all practical purposes refugees have all but disappeared.

I spoke with a number of knowledgeable locals, including representatives of international aid agencies and groups who of course spoke on the condition of anonymity. All of these sources agreed that the number of illegal North Korean refugees currently hiding in Yanbian does not exceed 10,000. Actually the estimates ranged between 2,000 and 8,000 people, with 4,000-5,000 seemingly perceived as the closed to the actual number. It is well below earlier levels of few ten thousand, even though these outdated estimates are still routinely cited by the world media.

Admittedly, these figures do not include North Korean women who have moved to the area in the last 15-20 years and entered de-facto marriages with local Chinese men. An unknown number of such women – perhaps a few thousand, or even more – have managed to acquire fake Chinese ID cards and have learnt how to pass for a PRC citizen. However, due exactly to the nature of their situation, these women try to maintain a distance from the refugee community, and work hard to assimilate into mainstream Chinese society.

So, even if the highest estimates are to be believed, there has been a 95 percent drop in the number of refugees in the area over the past 15 years. Why has this happened? The first reason is highly visible, intensification of border security has been dramatic.

From 1949 until very recently, the long border between China and North Korea remained all but unprotected. Both China under Mao and North Korea under Kim Il-sung were remarkably efficient police states, and illegal migrants had little chance of remaining unnoticed. In accordance with agreements between the two governments, border-crossers were extradited and faced harsh punishments as enemies of the Great Helmsman or Ever-victorious Iron-Willed General, as Mao and Kim were known in the official media at the time.

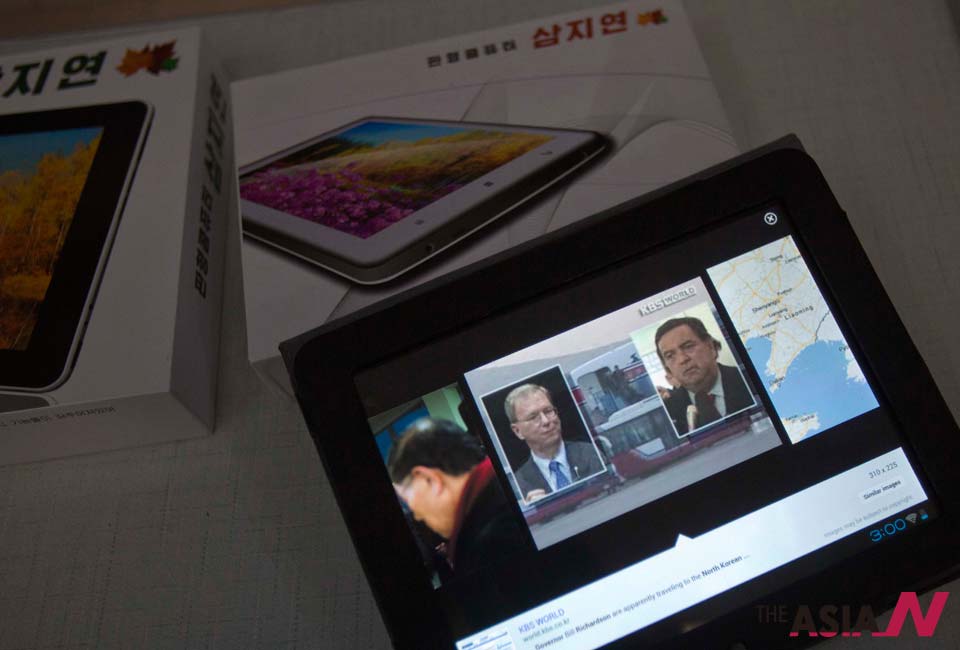

Social and political changes in China in the 1980s made the lives of North Korean border-crossers much easier. The new circumstances of China’s cutthroat capitalism made it easier for migrants to find job and shelter without too many questions being asked. The North Korean authorities also greatly softened its approach to refugees and began to see illegal border crossing as a relatively minor offense, to be punished only by a short-term imprisonment.

At the same time, the border remained poorly protected on the North Korean side and almost unprotected by the Chinese, so crossing itself was therefore a relatively easy task. The numbers of refugees in China would therefore swell to the above-mentioned 150,000-200,000 levels.

However, things have begun to change in recent years. From 2008-9, the North Korean authorities began to beef up security, with the number of patrols increasing significantly, and also began to frequently rotate the border guard personnel – a good idea, considering the fact border guards could easily be bribed to turn a blind eye at a smuggler or migrant.

Pyongyang did not limit itself to propaganda alone. Over the last year or so, the North Korean authorities have also started a rather noisy propaganda campaign in the media which attempts to persuade North Korea people that going to South Korea is not a good idea. In this campaign, South Korea is no longer presented as a ‘hell on earth’, they instead grudgingly admit that South Korea is quite rich, but still emphasize that North Korean migrants to the South have little chance of partaking in South Korean prosperity and are bound to remain second-rate citizens. The North Korean media even staged some press conferences with returned former refugees, who having had bitter experiences in the South chose to return to the tender embrace of the Great Leaders.

Therefore North Korea has begun to take the issue of refugees, hitherto neglected, rather seriously, employing both policing and persuasion to discourage its citizens from leaving. This new attitude has contributed greatly to the above mentioned decrease in the number of refugees.

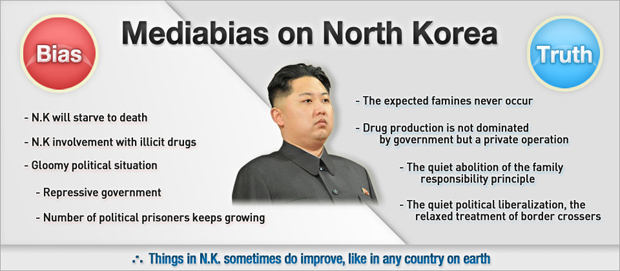

Changes can also be seen on the Chinese side of the border. In the past, the international media (generally speaking, US-dominated, and thus frequently biased against China) has on numerous occasions insisted that the Chinese authorities were beefing up their border security and even telling border guards to shoot at border crossers. From my own experience (as well as those of my trusted contacts in the area), I know that until recently such reports were largely or completely unfounded. The Chinese authorities did not bother to protect or even control the border. Apart from major cities, there were no fences, little real security measures, and patrols were a rare sight on the border itself.

This is no longer the case. In 2010-12, the Chinese authorizes have been busy constructing a barbed wire fence that extends across almost the entire Sino-North Korean border. In addition to the fence, CCTV and motion detectors have also been added, and the number of patrols has also been dramatically ramped up. As a result, an aspiring defector now faces far higher risks than a few years ago.

It is still possible to bribe the border guards to ensure a safe, even comfortable, passage, but the amounts involved have increased dramatically. In 2005, the going rate for an individual crosser was about $50 (smugglers and groups of course had to pay more), but now this figure is well above $1,000 and might reach $3-4,000. This is understandable: the guards need compensation for the considerable risks they are now taking.

The internal situation in North Korea also deserves some attention. The economy has improved significantly in the last 15 years, and as a result there is far less need to defect or seek employment in China for the average person. Malnourishment is still very common, but people do not starve to death in any significant number anymore. People can make a living at home and therefore they are less likely to consider the increasingly risky option of cross border migration.

Some changes in Chinese society are also quite important. In most cases, North Korean migrants have found assistance, shelter and jobs within the Chinese Korean community, which makes up about 30 percent of the population of Yanbian – they are concentrated in the vicinity of the border itself. Many of these people have begun to experience what is often called ‘donor fatigue’; they are less enthusiastic about providing their distant relatives with food and assistance. Additionally, a generational shift in this community is also working against North Korean refugees. Mass migration between North Korea and China stopped in the early 1960s, and the people who have firsthand memories of their relatives in North Korea are now getting old and dying out. The next generation of Chinese Koreans are understandably more reluctant to part with their money and resources in order to help their third and fourth cousins of whom they know little or nothing.

Whatever the reason, it now seems that the era of mass illegal migration from North Korea to China is over – for the time being, at least.

One thought on “NK’s effort to block defectors pays off”