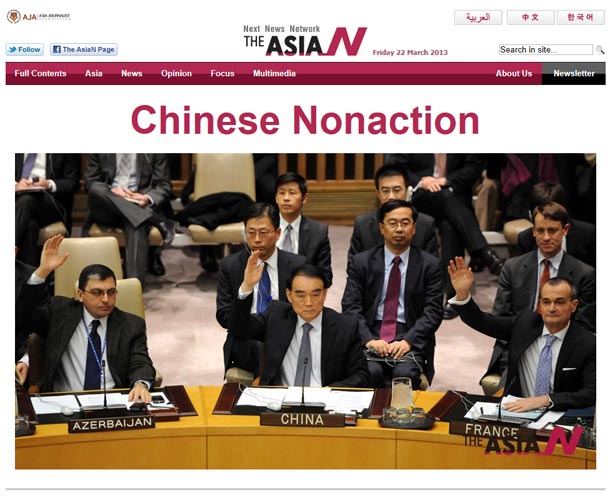

Chinese Non-action

Despite sanction, China remains staunch NK supporter

On the 9th of March, the Chinese foreign minister, Yang Jiechi held a news conference in Beijing. Predictably, one of the questions was about North Korea – after all, China just recently supported another tough resolution of the UN Security Council which condemns the North Korean nuclear test. Encouraged by this Chinese support and other news, for a brief while some people in Washington (and elsewhere) entertained the hope against hope that China will come to the rescue and will find new and efficient ways to deal with North Korea’s dangerous international behavior.

However, these people got a rude awakening. At the news conference, Jang Jiechi said: “We always believe that sanctions are not the end of the Security Council actions, nor are sanctions the fundamental way to resolve the relevant issues.” To translate from the diplomatese, “we voted for sanctions, but not going to be serious about it, and not going to press North Korea too hard.”

This statement was important and predictable. Chinese attitude to North Korea is somewhat controversial, and China does not like many actions by Pyongyang, but it still wish it to stay afloat.

The world media frequently describes China as North Korea’s ‘major ally’. This description is clearly a simplification of rather complex and uneasy relations that have existed between Pyongyang and Beijing for decades.

In spite of the usual rhetoric, and frequent professions of the ‘unbreakable Sino-Korean friendship’, China’s perception of the North was that of an arrogant, unpredictable and reckless neighbor that nonetheless has to be tolerated and occasionally coddled due to vital geostrategic considerations. Therefore, while both sides went to great lengths to demonstrate the amorous nature of relations, actual relations were often full of mistrust and tension – and have always been.

Nonetheless, China remains by far the most important provider of foreign aid to North Korea, and is also North Korea’s most important foreign trade partner (it controls some three quarters of North Korea’s external trade). China has occasionally expressed open disapproval of North Korea’s nuclear program, but it has usually been quite careful to not actually apply real pressure in the form of comprehensive sanctions. China’s stubborn reluctance to push North Korea hard enough is a major reason why the international sanctions regime has failed to influence North Korea’s behavior.

However, over the last year or so, there have been a number of signs that China’s attitude to North Korea has begun to change. In August 2012, the Chinese side chose to make public a dispute between Xiyang Group – a major Chinese mining company – and its North Korean state counterparts. Judging by what is known publically, Xiyang was cheated by its North Koreans. After the Chinese company built a mine in the North, the North Korean authorities proceeded to unilaterally change the conditions of the contract and went so far as to kick out the Chinese personnel, essentially taking full control over the mine.

This incident is not all that exceptional. As many foreigners who have dealt with North Korea are painfully aware, such ‘hostile takeovers’ are rather typical of North Korea’s particular style of vulture capitalism. However, this time the Chinese decided not silence the aggrieved party. Xiyang Group was allowed to publish a highly critical statement, and there is little doubt that this unusual act was approved by Beijing in advance.

In August 2012 another important event also occurred. A North Korean delegation led by Chang Song-taek – the uncle of the current Kim, and arguably the most important courtier in the realm – visited China to ask for additional assistance. They returned empty-handed, aside from assurances that the current levels of assistance would be maintained.

In January 2013, to the surprise of American and Russian diplomats, China’s UN ambassador decided to support a resolution of the UN Security Council that condemned North Korea’s rocket launch of December 2012. North Korea’s reaction was to threaten to conduct a third nuclear test.

This time the Chinese response was remarkably hostile. At one point, the Chinese official media even hinted that China would significantly cut its aid to North Korea if Pyongyang dares to test another nuclear device. A number of well-connected Chinese academics also aired their dissatisfaction with North Korea’s international behavior.

China’s ambivalence towards North Korea

Nonetheless, in spite of China’s protests and veiled threats, the third nuclear test took place on 12 February. For a brief while, many observers in Washington and elsewhere were hopeful that the final moment has come, and that Beijing will finally punish its supposed ally in an unspecified but meaningful way.

In a sense, such hopes are indicative of the current state of mind in the US political establishment. Events of the last two decades have indeed demonstrated that neither sanctions nor engagement has produced the desired changes in North Korean behaviour. Therefore, a growing sense of impotence has led US officials to look for alternative solutions and help from elsewhere. Of course China, with its seemingly immense leverage over North Korea, seems to be the possible savior.

However, events that followed the third nuclear test have vividly demonstrated that such expectations are misplaced. Even though the Chinese Foreign ministry expressed its indignation, and while it China will supported another Security Council Resolution, it is unlikely that Beijing will take measures necessary to have a significant impact on North Korean behavior. It is telling that the Xinhua news agency (the official mouthpiece of the Chinese government) immediately after the test issued a statement where it described the situation as resulting from imperialist pressure – i.e., pressure from Japan and the United States – which left the North Korean government little alternative but to go nuclear.

People may be disappointed with such a turn of events, but it is not particularly surprising and makes good sense from China’s perspective. There is little doubt that China is genuinely annoyed by North Korea’s actions, but great powers in general, and especially those run by an oligarchy, seldom-let emotions dictate foreign policy.

Contrary to what some China-bashers in the US sometimes say, China by no means condones North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. China is one of the five officially recognized nuclear powers, a privileged member of a very exclusive club. Naturally enough, China does not want new members to join the club, and it is also worried about the possible strategic consequences of North Korea’s nuclearisation (a nuclear Japan would be a nightmare for China) as well as about proliferation in general.

It is also true that China has significant leverage over the North Korean economy. If China wishes, it can essentially shut down the North Korean economy in a matter of weeks. This would push the North into economic collapse and perhaps another famine. But what would be the point of this? Such a dramatic step may indeed lead to North Korea’s denuclearization, but it is equally likely to lead to the disintegration of society, breakdown in law and order, anarchy and potentially revolution. This is clearly not what China now wants.

An imploding North Korea would send millions of refugees – some of them well armed and well trained military personnel – across the border to China. The crisis could potentially also lead to the private smuggling of nuclear technologies and materials. It might also result in the necessity of Chinese military intervention or, alternatively, lead to the reunification of the North with South, followed by the emergence of a pro-American, nationalist and democratic state on China’s borders. China can probably live with the latter, but it is clear that the status quo remains infinitely preferable.

If China were able to fine-tune its pressure on North Korea, hitting Pyongyang in a way to make it consider denuclearization but also not damage political stability, there is little doubt that Beijing would follow this path. However, fine-tuning seems impossible: the North Korean leadership is impervious to small pressures, and excessive heat might have dangerous consequences. As a senior South Korean diplomat put it in a private author with the present author a few years ago: ‘China does not have a lever when comes to dealing with North Korea, it has a hammer. It can hit North Korea unconscious if it wants to, but it cannot fine-tune North Korean behavior.’

China faces an unpleasant choice between a nuclear, adventurous but relatively stable North Korea on a divided peninsula, or a non-nuclear but unstable North Korea on a possibly unifying Korean peninsula. Both are unattractive to Beijing, but the latter appears infinitely more so for now. No doubt, China’s decision makers have again made the rational choice, opting for the lesser of two evils. This time, however, they did it rather grudgingly.