Pervasion of mobile phone in NK will eventually change it to a new country

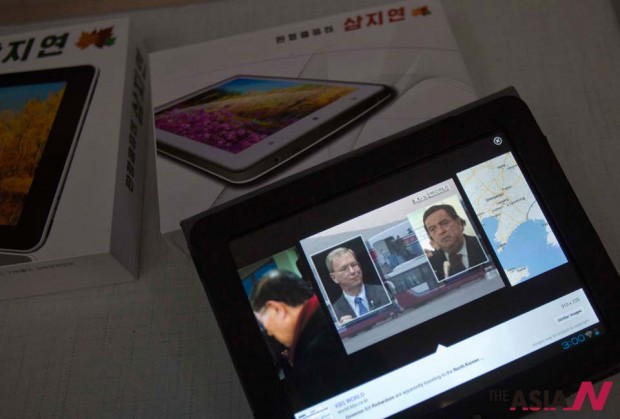

An image from a South Korean television website, showing photographs of Executive Chairman of Google, Eric Schmidt, and former Governor of New Mexico Bill Richardson, appear on the screen of a tablet computer running North Korean-developed software at the Korean Computer Center in Pyongyang, North Korea on Wednesday, Jan. 9, 2013. Schmidt and Richardson toured the facility to see demonstrations of North Korean computer technology. (Photo : AP/NEWSis)

In recent weeks, North Korea has frequently been in the headlines. Of course, the successful launch of a satellite attracted much attention. The large-scale purges of the military, the pregnancy of Kim Jong-un’s wife, Kim Jong-un’s New Year address and other news were widely discussed in the international media. However, foreign journalists have overlooked what might be the single most important piece of news to have emerged from North Korea in the last couple of months – according to official reports, the number of mobile users has exceeded 1.5 million.

It is not widely known, but the last decade has been a time of profound revolution in North Korea’s telecommunications industry. North Korea nowadays is not yet a wired nation, but North Koreans are still far better connected than they ever have been before.

Until the late 1990s, North Korea’s telecoms infrastructure was in an abysmally bad state. You would be laughed at if you asked a North Korean if he or she had a phone at home. Until ten years ago, a home phone was a rare privilege available only to handful of high-level bureaucrats.

Until the late 1990s, North Korea had no automatic inter-city dialling. In order to make a call to another city or province, you had to lodge a formal application at your local post-office and usually you could talk only at the allocated time. With the exception of Pyongyang and other major cities, there were no automatic exchanges, in the countryside a call would be put through by a ‘phone girl’ – essentially a technology from the dawn of the telephone industry, from the early 1900s.

These things began to change fast in the early 2000s. The North Korean government began first by rolling out a new and relatively modern phone network. Automatic exchanges became universal some ten years ago, and it also became possible to dial other cities as well (no overseas calls, though).

The number of people with phones increased dramatically within a few short years. As is usually the case with North Korea, no reliable statistics are available, but one can surmise that there must be a few million landlines in the country right now. My North Korean interlocutors usually claim that in the small towns around one third of all households have landlines nowadays while in Pyongyang this share may exceed 50%. Just 15 years ago, such things would have been unthinkable.

You can actually buy phone access by paying your local phone office. The amount – the equivalent of some $200-300 – is prohibitively expensive for the average North Korean, but can be easily paid even by a moderately successful market vendor. It seems that any self-respecting market vender would want to have a phone installed in his/her house.

Of course, the technology still leaves much to be desired. Intercity calls remain difficult or restricted. It is very common for two households to be connected to the same line and share the same number – this way of economizing was also common in the Soviet Union of the author’s youth, back in the 1960s and 1970s. Nonetheless, the phones are very much there in numbers that would have been unthinkable until very recently.

In addition, of course, there are mobile phones, whose recent proliferation has attracted so much attention overseas. This attention may to some extent be unwarranted, after all, landlines are every bit as important in many regards.

The first attempt to introduce a mobile service into North Korea began in the early 2000s. This ended abruptly in 2004, when mobiles were suddenly outlawed for all except a few hundred officials in the regime. The reason for the ban remain unclear to this day, though rumour has it that it is connected to the massive explosion at Ryongchon station. According to rumours, the Ryongchon explosion was an attempt to assassinate Marshall Kim Jong-il, whose armoured train happened to pass the station shortly before the explosion. Allegedly, the explosive device was triggered by a mobile phone. Personally, the present author is highly sceptical about these rumours, but the fact remains that in 2004 mobile phones were suddenly outlawed in North Korea.

They came back with a vengeance in late 2008, when the Egyptian telecoms company Orascom agreed to invest in the creation of a mass market North Korean mobile phone network (as a part of the deal, they also agreed to glass the massive pyramid of the Ryugyong Hotel, which had remained unfinished since the late 1980s).

At the time, this appeared to be a risky business decision, but it has turned out to be a remarkable success. Even though handsets are expensive by North Korean standards and it usually takes about a month to have an application processed, North Koreans began to sign up with great abandon. Nowadays it seems that an overwhelming majority of Pyongyang families have a handset. Mobiles have also spread to all major cities of North Korea. It has been reported by an Orascom CEO that “Coverage includes the capital Pyongyang in addition to 15 main cities, more than 100 small cities, and some highways and railways.”

This is politically significant because the new availability of phone links gives North Koreans numerous opportunities to talk amongst themselves, exchanging views and gossiping. Merchants (and North Korea is a country with a booming black market) use phones to receive up-to-date price information, to manage shipments, to arrange long-distance money transfers and the like. Without phones, such things would be far more difficult to do.

It also means that people can talk among themselves. In the past, the North Korean authorities worked hard to stop the emergence of horizontal connections between their subjects. North Korean society was extremely compartmentalised even by the standards of its communist societies in general. Intercity travel was heavily controlled and often not allowed. Mostly people interacted only with their immediate neighbours and co-workers. They had to be careful in what they said, secret police informers were omnipresent and this was widely known.

Things began to change in the late 1990s thanks to the growth of the market place. The market became a place not only for the exchange of goods and services, but also rumours. The emergence of mobile phones means that North Koreans will start talking among themselves with hitherto unthinkable frequency.

This does not mean that everyone is going to use a newly available phone to talk politics and other dangerous topics. The North Koreans are not so naive, and they understand all too well that the authorities are likely to eavesdrop on their conversations. Their fears may be exaggerated, however, since it is impossible to effectively monitor such a large and fast expanding network. It might have been possible to eavesdrop on conversations when there were 100,000 phones in the country. Now as the number stands between 4 and 5 million, this is a far more difficult task. One cannot increase the staff of secret policemen that fast.

Of course, there is modern voice recognition equipment which can concentrate on talks where dangerous keywords are mentioned and such equipment will be of some help to the secret police. However, as known by everybody with experience of life in an authoritarian system, such keywords can be easily avoided or replaced with some code phrases. There is little doubt that North Koreans will soon master such simple technique as well.

This is not to say that North Koreans will immediately start using the newly available technology and connections to plan a revolution. Most phone owners belong to the North Korean elite and have a vested interest in perpetuating the system. Nonetheless, the ability to communicate, to stay in contact with people far away is very important in itself.

We do not even have a proto-civil society in North Korea yet. Nevertheless, growing connections and easing access to the lines of communication as well as the resulting ‘de-compartmentalisation of the North Korean society’ (as a fashionable academic would probably put it) is an important first step in the creation of a new North Korea, whose people will be able to formulate and pursue their demands and arrange collective political and social actions.