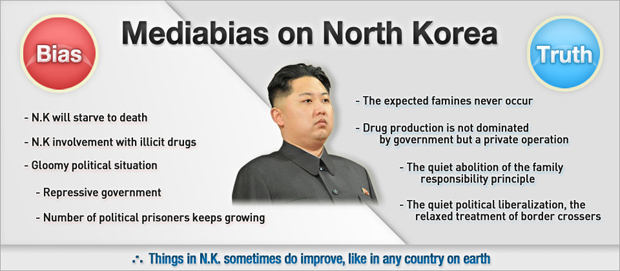

Mediabias On North Korea

North Korea does not get much good press in the global media. Its image is that of a bizarre, irrational and dangerously unpredictable place which is run by control freaks who ensure that every North Korean is a master of goose stepping and grenade throwing. If these stories are to be believed, the country lives in a state of permanent economic and social disaster. In this unlucky place, things can change only from bad to worse.

This unflattering picture is not completely unfounded. North Korea is a brutal dictatorship whose population is impoverished (generally) and whose main ideology is militarism (somewhat euphemistically known as ‘military-first politics’). Such features lead people to overlook some changes which have occurred in the North though. It is a bad place to be, but in many regards the situation is improving, even though these improvements are neglected by the media.

Every autumn the international media begins to run stories about the looming threat of disastrous famine which is about to descend on North Korea. Reputable media outlets cite assorted ‘authorities’ on the issue, and the said authorities assure us that by the end of the coming winter, a few ten or even hundred thousand North Koreans will starve to death.

These gloomy predictions are usually forgotten by the end of the winter, and for good reason: the expected famines never occur. But it does not stop the world media from running the same predictions the following fall once again.

Actually the economic situation in North Korea has been improving, on and off, for the last decade; of course a majority of North Koreans are still malnourished, but few if any have starved to death over the last few years. The Bank of Korea (the central bank of South Korea) estimates that over the last decade, economic growth in North Korea averaged 1.4% a year. Not spectacular, but also surely not a sign of deepening crisis.

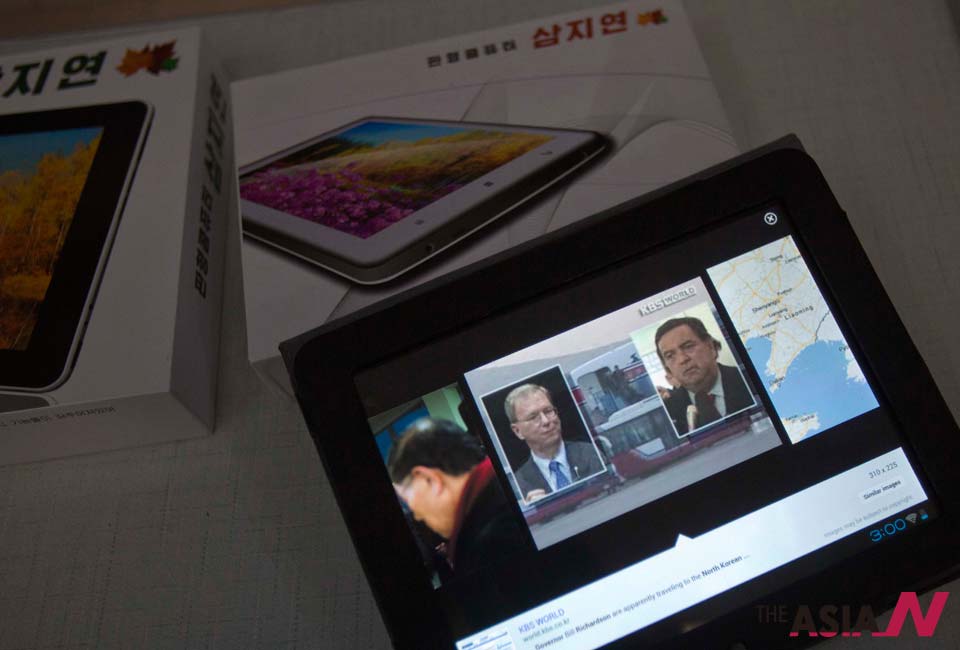

Indeed, North Koreans are not merely better fed and dressed nowadays. Landline telephones, once available only to a handful of top officials, can now be found in many urban households. And the number of mobile phone subscribers is well over half a million. Used computers are becoming more common and motorbikes can be found in many affluent families.

However, these signs of moderate improvement are seldom reported by the mainstream global media. Maybe it does not make for good news, but it is also equally possible that these developments do not agree with well-established stereotypes, and hence are neglected.

Of course there are also a small number of pro-Pyongyang media outlets, but they are equally reluctant to report these changes. They are usually run by the supports of Leninist socialism (the few who survived the near total extinction in the late 1980s) or some fringe groups of the nationalist left in South Korea. They tend to present the North as a surviving socialist paradise and hence cannot possibly admit that the triumph of consumer aspiration in this paradise is a fridge in the kitchen (now available to a steadily growing minority of North Korean families).

Reports pertaining to the political situation are equally gloomy. From time to time we are told that, in recent years, the North Korean government has become more repressive, that the number of political prisoners keeps growing. This narrative, however, appears to be quite misleading. The available information is incomplete and rather murky, but does nonetheless seemingly indicate that over the last two decades, the North Korean state has become less willing to imprison or kill its citizens (it still remains arguably the world’s most repressive society nonetheless).

One of the most interesting – and underreported– examples is the quiet abolition of the family responsibility principle, which might have been the single most infamous part of the North Korean repression apparatus. Since around 1960 and until the mid-1990s, the entire immediate family of a political prisoner, all people who were registered under the same address,had to be dispatched to a concentration camp. This is not the case anymore. Sometimes, immediate family members still suffer such a fate, but now this has become the exception rather than the rule.

Another example of quiet political liberalization is the relaxed treatment of border crossers – North Koreans who have illegally travelled in China in search of work, food and better income and then were extradited by the Chinese authorities (or intercepted on their way to China). The media sometimes reports the long-term prison termsof such people, but harsh treatment is reserved only for a few special cases – largely for North Koreans who have been in close contact with foreigners, especially foreign missionaries. The average border crosser if extradited from China, usually spends a few weeks in detention and then is released. This may sound harsh but this is nonetheless a major improvement, because until the mid-1990s, border crossing would lead to several years of imprisonment followed by lifelong discrimination.

If the above mentioned changes are not improvements in the human rights situation, it is not clear what is. These changes remain unreported though. The human rights advocacy groups either cannot bring themselves to admit that something has improved in North Korea or are afraid that such an admission might lead to a let up in pressure on the North Korean regime. Likewise, pro-Pyongyang groups cannot report such improvements because they cannot admit that for decades the allegedly ‘misunderstood’ and ‘vilified’ North Korean regime until recently sent completely innocent people – including children – to concentration camps only because of a real or alleged wrongdoing of their family member. Therefore, this type of news remains unreported because does fit either of the two dominant narratives that surround North Korea.

Another noteworthy example of the same bias is the way the media deals with North Korea’s involvement with illicit drugs. From the mid-1970s, North Korean stateagencies produced drugs for overseas sale. This was an unprecedented breach of international law, not to mention human decency, but the actual financial gains for Pyongyang were never very large. At any rate, the damage that such activities inflicted on North Korea’s international image far outweighed all possible monetary gains. It seems therefore that four or five years ago, the North Korean state finally made a good decision, either dramatically downsizing or ending it’s decades long involvement with illicit drugs production.

Decision makers in Pyongyang may have been driven not by late bout of guilt but by Machiavellian considerations: at the end of the day, the entire program probably did more harm than good to the North Korean elite. However, this change passed unnoticed by the mainstream media. When the present author was interviewed by a major American weekly a few months ago, I spoke about my research into this issue emphasizing that drug production in the North is no longer dominated by government programs but instead is now a private operation, done by individual drug dealers, whose actions are seen domestically as illegal (unlike the state agencies, who traded in opium, the individuals deal with methamphetamine). My findings were not quoted though and the story run by this weekly repeated old accusations aimed at North Korea’s ‘Soprano state’.

Fortunately I found have myself in good company: the same silence has surrounded the most recent report by the US State Department which also recently stated that the North Korean state either halted or has dramatically downsized its involvement in narcotics production and trade. These findings were published in March 2011, but only a handful of the major media outlets found this information to be newsworthy.

Does this mean that the North Korean state is the innocent victim of international media bias? By no means: it is a brutal, impoverished and at times a plainly bizarre place. That said though, one should keep in mind that things in North Korea, like in any country on earth, sometimes do improve, even though such improvements tend to go unnoticed or underreported when they do not fit the established picture or the prevailing narrative.

2 comments

This article makes some important points. As an American and an amateur DPRK observer, I can no longer put any credibility whatsoever into western media reports about DPRK. I don’t know whether it is sensationalism, intellectual laziness, or something more sinister, but Western “news” about DPRK is simply not reliable.

I can’t see the novelty of this. Home dvereliy in Argentina has been available from all major supermarkets for the past 10 years You do your shopping on their websites (from any device with Internet access), you account can store your past purchases, your usually preferred products, and it makes it a lot easier because you can customize the online supermarket to show only the products you like or usually purchase. We never ever go to a supermarket.