Memory of Kim Jong-il on the occasion of the first anniversary of his demise

One year has passed since the untimely demise of Marshall (posthumously promoted to Generalissimo) Kim Jong-il. Thus it is probably an appropriate time to say a few words about the deceased dictator, and perhaps to focus less on his shortcomings and focus more on the nicer parts of his personality and politics (and as we will see below, he had his brighter side too).

The present author talks to North Korean defectors regularly – a couple of times per week, perhaps. One striking thing that often comes up in conversation is the sincere respect that most refugees have for the late Generalissimo Kim Il-sung (the founder of the country and its leader until 1994). This contrasts markedly with the average North Korean refugee’s view of Kim Jong-il, a person held largely responsible for the country’s famine and economic collapse in the late 1990s, as well as for its continued economic crisis. In the popular imagination, Kim Il Sung tends to be seen as a great man, the true founding father of the nation and protector of the people, whose son was not worthy of his name.

This popular perception is dead wrong, but it is also quite easy to understand. In Kim Il Sung era (1953-1994), North Korea first, in the 1950s, experienced a short but rapid economic expansion which was soon followed by stagnation and then slow-motion decline. However, Kim Il-sung’s skillful diplomacy allowed the country to squeeze aid from the Soviet Union and China, and this aid was used to plaster over the emerging cracks in the increasingly dysfunctional system.

For the average North Korean, Kim Il-sung’s era was a time of predictability and iron-clad, if very moderate, social guarantees. It is true that this was also an era of massive state terror, when a near perfect police state was born and nurtured under the loving care of the Fatherly Leader. But this is now conveniently forgotten by the majority who still remember that back then at least everybody was given enough food to subsist (and not much more than that).

This dramatically changed in the early 1990s, and public opinion in the North clearly blames Kim Jong-il for this change for the worse. However, objectively speaking, Kim Jong-il has little actual responsibility for the economic disaster of the early 1990s and ensuing famine, which in the years 1996-1999 killed between half a million and one million North Koreans.

This famine was almost entirely the result of Kim Il Sung’s policies. It was Kim Il-sung who took Stalinist agricultural policy to its logical extremes – he did not merely put all farmers in state-managed ‘collectives’, but he even deprived them of all but the tiniest private plots of land. It was Kim Il-sung who created an agriculture which depended on massive inputs of chemical fertilisers which could be produced in sufficient quantities only so long as Moscow and Beijing were willing to foot the bill. It was also Kim Il-sung who insisted on electricity intensive pump-driven irrigation systems which instantly became unviable without foreign aid money. With all this, the famine was inescapable, and it clearly was not Kim Jong-il’s fault that the inescapable happened.

It is true that Kim Jong Il had some ways to stop the famine once it had begun in 1996. The solution was well known from the experiences of China and Vietnam (the latter country also experienced a famine in the mid-1980s, only to become the world’s third largest exporter of rice 10 years later). One had to disband the state-managed farms, and at the same time allow farmers to work on their own plots and dispose of their harvest as they like.

Kim Jong-il did not apply this solution because he believed, rightly or wrongly, that such reforms in a divided Korea would be politically dangerous and might put the domestic stabilities under threat. Marshal Kim did not want to be overthrown, and in this regard he was not different from every single state leader. Therefore, he chose not to continue with his father’s agricultural policies, ensuring political stability, but also sacrificing the lives of common people. This policy decision might indeed be reprehensible, but it still was not Kim Jong Il who brought about the famine.

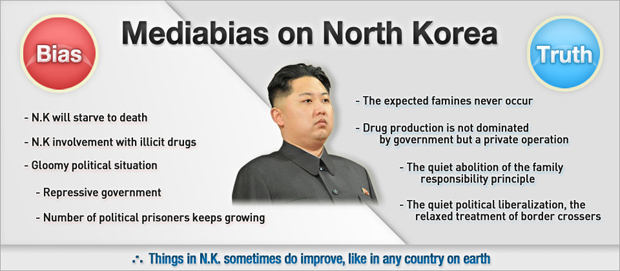

To give Kim Jong-il his due, once the disaster struck, he showed some measure of flexibility, even though the regime’s survival has clearly remained the bottom line. He was usually willing to turn a blind eye to the booming black markets, as well as to the spontaneous growth of illegal and semi-legal private agriculture. He also swallowed his pride and broke with the decades-old propaganda tradition of presenting North Korea as an earthly paradise where nothing could possibly be wrong. Under his watch, North Korea admitted that it had massive and devastating food problems, and explicitly asked for foreign aid (it did not hurt that Kim Jong Il also skillfully used a nuclear program and missiles to attract foreign attention to the sorry state of his kingdom and blackmail them into providing more aid).

The relative tolerance towards spontaneous marketization and the arrival of large-scale foreign aid made it possible for North Korea to overcome famine. So from the early 2000s the average North Korean frequently remains malnourished, but seldom faces the real possibility of starvation.

Another unnoticed and unsung achievement of late Marshall Kim Jong-il was the considerable relaxation of domestic political terror. Under his watch, North Korea has arguably remained the world’s most repressive police state, with some 150,000 people being imprisoned in huge labour camps for political crimes. Nevertheless, the level of repressiveness declined if compared to the times of Generalissimo Kim Il Sung. Partially this relaxations was a result of widespread official corruption (enforcers were willing to look the other way if sufficient bribes were paid), but in many cases it was clearly Marshal Kim who made laws more forgiving.

The most remarkable change was the partial rejection of the so-called ‘family responsibility system’ in the case of political crimes. In Kim Il-sung’s era, not only a political criminal, but also his/her most immediate family members (those who shared a household registration with the culprit in question) were to be shipped to prison camps. From the mid-1990s, this notorious rule ceased to be applied universally, there are still cases when family members are incarcerated along with the criminal, but in most cases, they are left alone, though they still face serious discrimination in their daily lives.

Another sign of mild political relaxation is the relatively lenient treatment of border crossers – those North Koreans who fled to China. In the Kim Il-sung era, border crossing was treated as a serious crime usually punishable by several years in prison followed by lifelong discrimination. Soon after Kim Jong-il’s ascent, official attitudes changed, and the vast majority of border crossers could get away with spending only a few weeks or months in a relatively mild incarceration centre. Such a massive shift of policy was largely necessitated in the dramatic increase in the number of border crossers, but it would have been impossible without the direct endorsement of Kim Jong-il.

Kim Jong Il did not know what to do with the booming private markets. He and his advisors vacillated between near open endorsement of the market economy (this trend culminated in the short-lived reforms of 2002) and attempts to wipe out private business (the embodiment of this approach was the disastrous 2009 currency reform). However, it seems that Marshall Kim Jong-il was usually willing to tolerate private economic activities, as long as such activities did not openly threaten political stability within his country. This might be somewhat cynical, but it would clearly have been much worse had Marshall Kim been a sincerely zealous ideologue who really believed his regime’s anti-capitalist, anti-market propaganda.

What little that is known about Kim Jong-il’s personal life also creates a favourable impression of this man. While he was certainly a serial womanizer, he took great care of his exes and their children (this “great care” often meant a few hundred extra dead farmers, but let us overlook this for the time being). He was also quite charming, in spite of his odd hairstyle and looks – this is a point stressed by many foreign dignitaries who met him.

Marshal Kim was often willing to forgive things that which his father would never have tolerated. For instance, when Kim Jong-il learnt that one of his former bodyguards was intercepted in China while attempting to flee to South Korea, and kidnapped by the North Korean agents, he ordered that the man be released from prison after merely one year of incarceration. The bodyguard after his release managed to get to the South. In another case known to the present author through personal contacts, Kim Jong-il allowed an aging engineer whose entire family was living in China to legally leave the North and move to China, even though permanent emigration is completely illegal in the North.

The late Marshall Kim Jong Il was a man who was unlucky to be born in a family of hereditary dictators. Under other circumstances he would probably have become a well-respected cinema producer (his ardent love of cinema is well known) or a mid-ranking office manager, known for his good heart and caring approach to the employees. But this was not his fate. He had to deal with a country which had been saddled with the heavy legacy of his father, a legacy that bequeathed to him economic ruin, social stagnation and police state.

One cannot say that Kim Jong-il did what he could to solve the country’s problems, largely because for him the survival of the regime (and, by extension, the political and perhaps even physical survival of himself and his family) remained paramount above all other things. He therefore never seriously considered policies which while beneficial for the majority would have put the regime under threat. Nonetheless, within the very narrow limits of the existing system, he often did what he could to ameliorate the sufferings of the people.

One thought on “Memory of Kim Jong-il on the occasion of the first anniversary of his demise”