Exhibit shows cartographic history of last kingdom

In Park Bum-shin’s novel “Gosanja (Man of the Mountain),” Kim Jeong-ho, a cartographer and geographer of the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910), struggles to make accurate maps despite opposition from the aristocracy. It portrays the cartographer’s difficulties in delivering the exact topographic information as the ruling class used maps to expand their ideologies.

In fact, the Joseon maps were mostly used by its ruling class for political purposes to justify their ideology. Ordinary people could not access maps. They were pictorial rather than accurate as it was feared that detailed information could reveal state secrets.

Such characteristics of the Joseon maps are on show at a special exhibition titled “Cartographic Achievements of Joseon” at the Seoul Museum of History through Feb. 28.

The exhibition displays some 50 items comprised of maps and books produced during the Joseon Kingdom donated by the late geographer Lee Chan and art historian Hur Young-hwan who had collected them throughout their lives.

The exhibition is designed to showcase the cartographic development history and geographic perceptions of that time. It includes such rare maps as “Joseon Paldoyeoji Jido” from the 16th century, the oldest extant printed map in the nation.

In general, the Joseon maps are painting-like, meaning there is more emphasis on the land and mountains rather than geographic accuracy. They show the Joseon people didn’t use maps only to navigate but to present their world of thoughts.

The first section of the exhibition introduces the 600-year history of Hanyang — what Seoul was called then— through 10 maps depicting the capital from the Joseon era to modern days. Mostly the Joseon map of Hanyang symbolically shows the dignity of the kingdom by depicting the exaggerated sizes of royal palaces, shrines and castles. The mountains are drawn like a painting, revealing the authority of the rulers.

The maps made in the 19th century when the nation opened its doors to foreign countries mark the locations of foreign legations, which represent how the nation was under foreign power.

However, under Japanese colonial rule (1910-45), the maps show that the capital lost its function. Gyeongseong (the then name of Seoul) was incorporated into Gyeonggi Province at that time and the kingdom’s symbolic structure of the capital was realigned for the interests of the Japanese colonial government, for example, demolishing the castles. After the liberation, the maps display the restored functions of the capital.

In the second part, the exhibition demonstrates the progress of cartographic skills in the Confucian state. As the rulers were deeply interested in making the maps, cartographers accumulated geographical skills such as measuring distance and altitude. However, in depicting the terrain, the northern regions were expressed very inaccurately. It was only toward the end of the Joseon period, with the development of more advanced cartographic skills such as “Baengnicheok,” a scaling measure, that the northern regions were drawn more accurately.

Despite these skills, the Joseon maps contain the exaggerated Mt. Baekdu and the long-stretched mountain range starting from Mt. Baekdu in the north to Mt. Jiri in the south with five colors like a painting. Also, the exhibition captures the intriguing points of the people’s thoughts of the world through their world maps. Particularly, “Cheonhado” reflects the imagination of the Joseon people in portraying China as the center of the world.

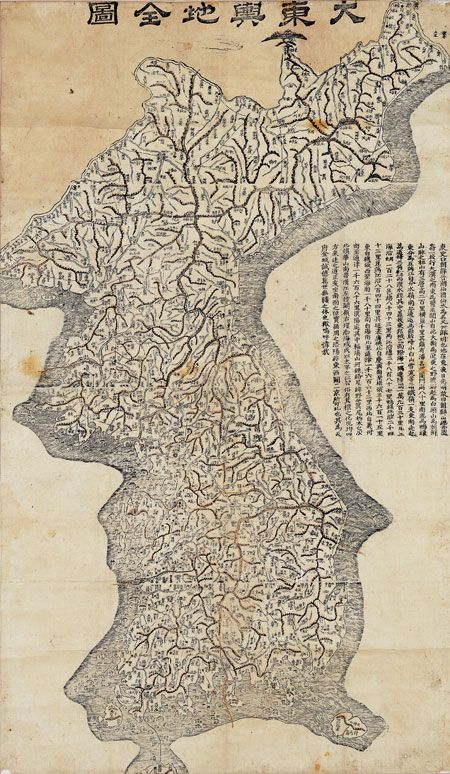

“Daedongyeojido” (Detailed Map of the Great East) from the 19th century by Kim is in that sense a great achievement which includes more detailed information with marking the mountains, rivers and roads, through dots and lines, which is close to modern maps.

The late Lee and Hur donated the collection to the museum in 2002 and 1996 respectively. The exhibition also shows an interview with them.

For more information, call (02) 724-0274-6. Admission is free. <The Korea Times/Chung Ah-young>