Elusive chaebol reform

Candidates struggle to find ways to overhaul conglomerates

This is the second in a four-part series analyzing and comparing key election pledges on economic policies promoted by the three major presidential candidates. — ED.

Desperate to massage the egos of credit-crunched voters, presidential candidates from both the left and the right are vowing to bring the fight to billionaire corporate rulers, frequently accused of monopolistic behavior and illegally stockpiling of wealth.

But while they talk the talk about taming chaebol, or the country’s mighty family-owned conglomerates, their dearth of ideas suggests they aren’t as prepared to walk the walk.

The presidential race remains a mess. About a month left until the polls, Park Geun-hye, daughter of late president Park Chung-hee and ruling Saenuri Party candidate, still doesn’t know whether she’s up against Democratic United Party (DUP) representative Moon Jae-in or independent Ahn Cheol-soo or both. It currently looks like the single candidacy talks between the two will have more false endings than the third Lord of the Rings movie.

Adding to voter confusion is that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to tell the three candidates apart by anything other than their appearance. Park insists she represents a new branch of conservatism that better defends working-class Koreans. Liberal flag bearers Moon and Ahn speechify about equality and social mobility but also vow to put economic growth before those agendas.

The sense of sameness extends to their predictable and familiar suggestions about reforming big business and “democratizing’’ the economy, all borrowing heavily from the sky-is-blue school of thought.

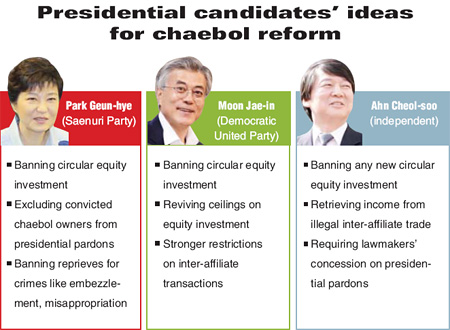

Park, Moon and Ahn are a chorus when talking about stemming the chaebol practice of “circular equity investment,’’ which has allowed them to weave a complex web of corporate ownership that accelerates the transfer of wealth to their founding families.

All three of them promise sterner punishment for corporate crimes like fraud, embezzlement and misappropriation of funds. They call for ending the tradition of lax justice for wrongdoing chaebol bosses, who have been granted reprieves or presidential pardons on crimes that cover a range of business irregularities. There are a few different wrinkles between the three candidates should one choose to look carefully.

Moon and Ahn display a stronger passion than Park on the issue of restricting inter-affiliate trading, which has touched off anti-competition disputes by accelerating the concentration of economic power to business groups atop the totem pole. The liberal candidates also represent a nearly identical voice in protecting the autonomy of financial companies against industrial capital, an area Park seems reluctant to visit.

Moon talks about reviving the ceiling on corporate equity investment to restrict how much business groups can invest in its own subsidiaries but Ahn has been vague on the issue.

It remains to be seen if any of the candidates will manage to put their money where their mouth is when they unpack at Cheong Wa Dae, when large firms continue to be the beating heart of the country’s export-dependent economy. And even if they do, it’s hard to imagine the actions having any meaningful affect on changing the influence chaebol have on Korean lives and business.

Samsung Group serves as the example of the circular equity investment. Samsung Electronics Chairman Lee Kun-hee owns 20.76 percent of Samsung Life, while Samsung Everland, essentially the holding company of the Samsung business empire, is the second-largest shareholder with a 19.34 percent stake. And the majority shareholder of Samsung Everland is Lee’s son, Jae-yong, a Samsung Electronics president.

Essentially, this means that Chairman Lee gets to maintain dominant control over his corporate empire by leveraging the assets of Samsung Life’s insurance customers.

The downside of putting so much focus on circular investment is that Samsung virtually represents the only example of it. Restricting such practices will have no affect on how businesses are run at other family-owned conglomerates like SK and LG.

Limiting companies’ investments in their subsidiaries presents the opposite problem: That would affect SK and LG, but not Samsung, the undisputed kingpin of Korea Inc.

Besides, Park and Ahn are talking about only curbing “new’’ attempts at circular investment and letting the current ones stay. Anyway, Moon promises a three-year “grace period’’ for companies to resolve their circular investment structure so the Samsung chairman probably isn’t losing any sleep.

Perhaps the most disturbing truth of this monotony is that none of the three candidates have shown an ability to attack the core of the chaebol problem. The dominant presence of a small number of elite firms has compromised the country’s ability to create jobs by eliminating competitive parity in major markets and suppressing entrepreneurship.

Since recovering from the late-1990s financial meltdown, Korea has had a succession of leaders in Kim Dae-jung, Roh Moo-hyun and Lee, whose export-supportive economic policies have consistently favored big corporations. Inequality, the inevitable result of this approach, was considered as something that should be tolerated as the cost of national prosperity.

However, the strengthening argument is that this polarization has hurt the country’s long-term growth potential and made it more vulnerable to financial downturns like the current one, where exports dip amid worsening global conditions.

Even as Korea’s growth in gross domestic product has pulled back sharply in recent years, the country’s leading business groups have been setting record on record profits. Despite sitting on piles of cash, the companies have used only a tiny proportion of this on productive investment and have been rapidly replacing their workforce with precariously employed laborers.

The household debt mountain now matches an entire year’s gross domestic product and consumer activity is in a coma, cutting off an important route of economic recovery for the country.

It will be critical for Korea’s next leader to find a way to boost incomes more broadly, especially at a time when the country is beginning to face the challenges of an increasingly top-heavy population structure. Regrettably, none of the three candidates seem intellectually prepared to do this.

Moon is at least attempting to take a stab at the issue, vowing to restrict the proportion of precariously employed laborers at chaebol and have them grant permanent status to more of their existing non-regular staff. However, he can’t say these things without expressing concern about how that would financially burden the corporate heavyweights and taxpayer money will have to be spent to compensate that.

“Those who have the most have been behaving unfairly the most and breaking this is the first step toward economic democratization,’’ Ahn said Thursday in a meeting with chaebol leaders at the Federation of Korean Industries in Seoul. Indeed. In other news, the sun came up. <The Korea Times/Kim Tong Hyung>