Tales of Korean Treasures ②

• Influences of the Silk Road

I may not be wrong when I say that Korea’s ancient kingdoms which rose along the Silk Road made their arts communicate with their neighbours. That’s why their traditional handicrafts, popular habits and even tales were influenced by such proximity. Moreover, such influences went beyond the boundaries of China to areas along the Silk Road. In Goguryeo tombs, archaeologists discovered a style of architecture similar to the one found in Afghanistan in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, especially in the tombs of the kingdom of Bactria on the Tilia Tipi plateau, northern Afghanistan.

As a matter of fact, craftsmen who travelled cross the Asian continent, looking for better job opportunities and settled in the Korean peninsula, carried their fine workmanship with them. That explains the discovery of similar earrings spread over the royal Shilla tombs. Such travels by craftsmen were common in all ages as more revealed by the paintings of high horses in Goguryeo tombs. Similar paintings were found in west Asia, indicating that entertainment and sport, whose traditions were established in foreign lands, have later become part of the lifestyle of the Koreans and the Japanese.

Influences were not attributed to immigrant workers in Korea alone, but other influences were brought by the visits of Korean Buddhist monks to India, which made the Indian sub-continent and its Buddhist arts a source of inspiration for the rock inscriptions found in the Kyong-ju area, as well as the paintings of Korean monks on a mural in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

People travelled, carrying valuable possessions, many of which settled in Korea. That’s how archaeologists unearthed jugs and glass cup probably made in Cologne or Syria.

According to a tale about King Taegu, the founder of the Koryo dysasty that on his deathbed he said, “Koreans are in no need to copy Chinese tastes with humiliation.” Therefore, workshops were set up in the Kaesong economic zone proudly exhibiting their “Made in Korea” products; despite the fact that the designs of some luxury goods, such as mirror decorations, are strikingly similar to those found in China.

• Earrings for men and women

But Korea’s exclusiveness which the king called for was found in the pair of rings registered under No. 90 among the Korean treasures in the National Museum, the closest to the arts of the kingdom of Shilla, which provided more earrings than any other cemetery in the world. This pair of earrings, together with the famous gold crown, are examples of the thousands of necklaces, rings, belts and shoes which were buried with the dead kings and queens of the kingdom of Shilla (57 BC – AD 935) in its capital Kyong-ju. The upper part is a ring; the back part consists of tortoises, a symbol of long life. To the pair of earrings 27 pieces of gold jewellery are attached, about double the number in similar earrings at he time. What explains the large number of earrings is the fact that they were worn by men and women alike. Kings and queens did not wear earrings, but crown princes did. Women’s earrings were thicker than men’s. This 8.7 cm long pair dates back to the 6th century AD.

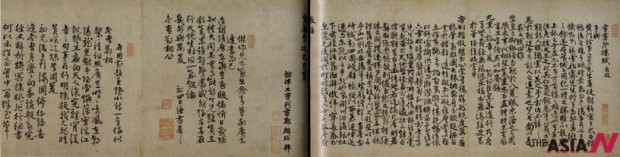

Let’s go back to life before, not after death, as a single manuscript can reveal an entire age. That’s what I felt when I read a translation of this document which dates back to AD 1401, and in which King Taegu, founder of the kingdom of Chosun, upon his abdication bequeathed his daughter Soskin, born of a mistress, a house and a plot of land. According to arrangements the daughter had to buy his prime minister’s house, slaves ordered to cut the necessary wood to repair the house, which he wished to be for his daughter and her grandchildren in the future and for ever!

It’s worth noting that many Korean manuscripts were seized and sent to museums outside Korea, such as in Japan and France during recent wars. At its insistence, the Korean government succeeded in regaining some of these documents, including the book Yugoy, which contains diaries of the protocols and celebrations of the ruling Chosun dynasty (AD 1392-1910), returned to Korea from France this year.

• Poetry has its share in Korea’s treasures

Not only does the museum house documents of selling and buying wills and royal court decrees but poetry also has a share in its treasures. In AD 1450 (the thirty second year of the reign of King Sejong) the Chinese Ming dynasty sent envoys announcing Emperor Ging-Di’s accession to the throne.

The mission was headed by the Chinese ambassador NI Gyan who exchanged poems with the scholars of the ruling Chosun dynasty, including Ingi. The museum exhibits scroll containing 35 poems, kept in a special case, with an introduction by the Chinese minister Wang Shwan.

However, all what the museum houses is something and what is related to Buddha is something else. You suddenly discover that life is entirely… Buddha. In a medium-sized room we all stared at a glass box which exhibits a ‘feminine” image manifested in Bodhistava’s contemplative statue. Buddhism entered the Korean peninsula in the 4th century AD, adding a lot to local arts and developing the country’s culture. As far as studies of Buddhist art are concerned, the origins of Buddhist sculpture during the period of the three kingdoms (57 BC – AD 668) and the united kingdom of Shilla (AD 668-935) should be considered. Buddha’s statues are therefore a key area of Korean art, providing some of the finest pieces of sculpture from the artistic point of view in East Asia and the world. There is no reference in history books to Korea’s religion, if any, before the advent of Buddhism. Therefore, as usual, religion helped art flourish. Buddha’s image was first carried by Buddhist monks from China, and other images appeared in India and central Asia. It’s as if the Korean influence had shaped all those sources and left the taste of Korean craftsmen on the Korean Buddha influenced by local artistic traditions. As I looked carefully at contemplative Buddha I found the purely Korean face surmounted by a crown similar to Sassanians’ crowns in Persia in terms of length and decorations which combine the moon and the sun! But the enigmatic smile, normal sitting posture, symmetric body and harmonius clothes, half of all of which mirroring the other half, make contemplative Buddha an extraordinary piece.

As we leave a hall we walk along a modern corridor with a huge balcony overlooking a lobby which accommodates the extremely tall pagoda (ten levels, 1350 cm high), a minaret–like building. Like the museum, the pagoda itself moved a number of times. It was first put up in Gyong Chonsa monastery in the fourth year of the reign of King Chong-mok of Goguryeo (AD1348). In 1907, it was secretly and illegally smuggled to Japan by Tanaka Kokin, a Japanese royal courtier.

The pagoda was returned to Korea in 1918, thanks to the efforts of two journalists: A. Beethill (British) and H. Hilbert (American). It was put up again in Gyong Chonsa Palace in 1960, but archaeologists found it hard to keep it intact due to weather conditions and acidic rain, and was therefore dismantled in 1995, and when the National Museum of Korea was opened in its current location, the pagoda was put up there in what is called the “Path of History”.

• Buddha … waiting for me

Because of the very many pieces of information I received from the Korean guide during my town I imagined everything round me like Buddha. From the panoramic view of Seoul from the tall window you can see some historical palaces with their pretty gardens amid modern buildings with green roofs. To my surprise, Buddha was waiting for me there, as the hotel management put a copy of The Teachings of Buddha in the desk drawer: an elegant edition in about 850 gilded pages in Korean, Chinese and English, with a golden and a red ribbons. At the beginning and end of the book there is a list of the locations of Buddha’s statues. As mentioned in the introduction, Buddha’s words are recorded in over 5,000 collections kept and circulated for more than 25 centuries ever since he left his home in the 5th century BC to go down the road to wisdom, and his words, wisdom and teachings spread all over India during the reign of King Ashoka (268-232 BC). Under a modern lamp I read the words of the “Candle of Asia”, as he is called:

“There was a king who ruled his country successfully, and in view of his wisdom he was called “the greatest light”. Explaining the secret of his success he says: The best style of rule that a king should adopt in his country is to rule himself first. A ruler must present himself to his people as a man whose heart is filled with love. Moreover, he must teach and even lead his people to clear their minds of all evils. Common happiness resulting from good commandments is better than the pleasures of worldly material things. Accordingly, the ruler’s good commandments to his country secure peace and tranquillity for his people’s minds and bodies. When a miserable person comes to him he must open his treasuries and let him take whatever he wants. He must seize the opportunity to teach his people the virtue of getting rid of what they do not need and with it they get rid of greed… Whoever has good teachings sees every beautiful light in trees; greedy persons do not possess the virtue of controlling minds, and are blind even in front of the lights of a golden palace.”

I had a deep desire to go back again to the National Museum of Korea in the morning. I wanted to thank Buddha and all good people in this world. We need to get all good words out of the museum’s heart, to make them a lifestyle and a code of tolerance towards others. That’s the journey which begins and ends with good words, where legends mix with history, and the search for mix who develops the world continues, leaving treasures in the world’s memory for the future generations.