Tales of Korean Treasures ①

As you go through the country’s National Museum, you feel as if you were passing from one age to another. In this way you leave a face which represents Seoul’s contemporary present to a space which embodies the history of the Korean nation. But in the depths of these ages you will find that there is a close connection between what man was there and what he became later. It’s the extended tales like family members passing on their genes from ancestors to descendents.

In Danyang, in the province of Chungcheong, the legend of “Ondal the Fool” is told. Ondal began his life as a foolish beggar in the northern kingdom of Goguryeo, one of three kingdoms later untied founding the Korean nation. There was then a princess who drove her father all but mad because of her continuous crying. Her father, even for fun, threatened her to stop crying or else he would marry her to “Ondal the Fool” when she had grown up.

As the young princess grew up she became a beautiful and wise girl. Her father called princes to line up so that she would choose a husband from among them, but the princess refused to see anyone of them and told her after that he should fulfil his promise and marry her to “Ondal the Fool”, which he did, meeting his daughter’s wish. After marrying the princess, the foolish man changed completely and even became the best military leader in the kingdom of Goguryeo. This story proves that honesty, faithfulness and insistence can bring considerable success out of nothing.

Is that a legend? As a matter of fact Ondal is reported in history books rather than in legends. His military achievements are documented, and there is a picture of him at the castle of Ondal mountain which he built 1,500 years ago to defend his country against the warriors of the kingdoms of Shilla and Baekje. The legend might have combined a backward past and a bright present. That’s how nations are established, as they prove that they can bring about change when they have principles, which is the essence of Korea’s revival.

• A journey to a museum

We will come down Acha mountain, where brave Ondal was buried, on our way to the Han River, which looks like the River Nile in parts of it, where the National Museum of Korea is located. Behind each piece there is a tale worth reflecting on as well as telling.

Treasures are the most precious items and objets d’art which historians and experts regard as valuable things. Valuable things today may be clothes designed by a contemporary artist for film or sport stars, the political elite or new generations’ fashion. But the treasures we will tell about derive their value from the river of eternity. They are original works from different epochs of history, with unique designs whose beauty no eye can resist and whose moral value no mind can miss.

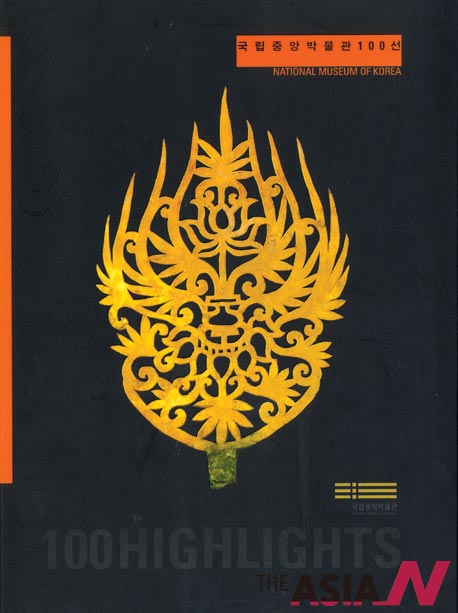

Fifty years ago, the Treasures of the National Museum of Korea album was printed for the first time, coinciding with the movement of the museum from Saeokgun in Deoksu Palace to another building in Gyeong bok Palace (which became the Museum of National Popular Arts later). In 1972 the album was printed in colour entitled 100 Treasures, though it contains 118 pages, but the publisher’s love of zeros (100) made him choose that number. An album of the collection of the Korean treasures was printed in 1986 to coincide with the museum’s movement to the Capitol. The album also contained the previous items discovered in the 1970s and 1980s and added to the museum, though may treasures of Buddhist art and manuscripts were not listed.

In 2006, a year after the museum moved to its current site in Yongsan album entitled 100 Lights was printed, which the museum invites you not to miss, out of 4,500 items housed by the archaeological section which consists of 11 historical sections. In addition to these holdings there are exhibitions of Korean and Asian arts, including a model of the first innovation in the world for metal printing on stone, and on manuscripts at the Hangul historical exhibition.

• Gifts

I start with the Gifts Exhibition, out of my genuine desire to make the principle of giving gifts to our Arab national museums something common. It is fine that someone gives their country’s museum a national treasure. The section houses a thousand items given to the museum a little before its latest opening. Since 1946, more than 200 persons have given about 22,000 items to the museum, which accounts for 10% of its total holdings.

In 1875, Germen archaeologists found a Greek helmet dating back to the 6th century BC used for the praise to God ritual following winning in the ancient Olympics. In the 1936 Berlin eleventh modern Olympic Games runner Son Kijung (1912-2002) won the gold medal in the marathon and was awarded the archaeological helmet in recognition of his achievement, but he did not receive the helmet which the Germans kept in the Berlin Museum until it was returned to him in 1986, Kijung believed that the helmet was not his property but the property of the Korean people and, therefore, donated it to the National Museum of Korea in 1987 where it is kept among its treasures under No. 904!

Before we see the museum’s holdings of Korean treasuries let’s go to another section which houses Asian arts. This means that the museum dedicates part of its memory to celebrate its neighbours. An example of this is a magnificent horse of white clay which after being formed is put in a 1100˚C. oven to be painted, then heated again to 900˚C. The colouring layer is made of lead and quartz, which makes it transparent in fire, and with oxidation it turns into its three colours: oxidized copper becoming yellow, oxidized iron yellowish brown and oxidized cobalt indigo blue. This 546 mm-high horse was returned to Korea during the age of the Chinese Tang dynasty in the early 7th century AD. From the Asian treasures also I’ve chosen from Japan a collection of boxes and furniture of an aristocratic bride of the 19th century, consisting of what women need in their daily life, such as tables, toothbrush, cosmetics and sewing boxes, tea set, mirrors, etc.

• The duck cup and the gold crown

Among the Korean treasures dating back to the 13th century AD age of the three kingdoms you will see a pair of big ducks (32.5 cm high). Tea is poured from above into the duck’s hollow body and is drunk from its rear. These and similar pottery objects were used for drinking during funerary rites and were buried with the dead body later, as ancient Koreans believed that birds, mostly ducks, would lead the dead to paradise.

Did everybody take birds to their graves? This question occurred to me as I was looking at some of the jewellery discovered in King Muryeong’s cemetery, the only one of the age of the three kingdoms which had been identified. Seventeen gold jewellery pieces were spread over the cemetery, and all these have become national treasures reflecting the real art of the kingdom of Baekje, which is completely different from the two other neighbouring kingdoms of Goguryeo and Shilla. This 226 mm crown was found in the queen head’s place.

The other crown I’ve chosen (273 mm high) from the kingdom of Shilla, dating back to the 5th century AD, was dig up in the northern cemeteries with a silver belt on which is inscribed “the Lady’s Belt”, indicating that the cemetery belonged to a lady of a royal family in view of the value of the gold find.

The crown’s design resembles tree branches or the horns of an ibex, which reflects a Korean belief that trees act as a mediator between the earth and the sky and its roots spread down far from the ground, with its branches stretching high in the sky. The ibex’s big horns symbolize a reindeer, known as “the sheriff of the forest” and is a symbol of long life. The basic structure of the crown is decorated with gold-coated, jade-studded twisted wires whose rustle is heard and scattered light seen with every movement, like tree leaves in a golden forest, with the jade like wings symbolizing abundance and fertility.

(*To be continued)