Ancient construction secrets to be shared

Asian master carpenters to meet in Suwon

History is well reflected in traditional architecture, giving awe and admiration to its beholders. But few know how the structures were built and who designed and constructed them and how they were preserved until today.

In East Asian nations with a long history of wooden architecture, construction techniques have been handed down by a handful of skillful master carpenters in charge of the whole process from design and choice of materials to finish.

However, there have been rare chances to peep into the world of the master carpenters crucial in revitalizing wooden structures in East Asian nations.

The Suwon Hwaseong Museum is hosting an exhibition and a forum to showcase the artistic features of the wooden structures and the time-tested skills of three Asian master artisans.

The exhibition will showcase some 100 relics from traditional masterpieces from Oct. 24 to Jan. 30 in 2013.

“It is the first of its kind to focus on the ancient architecture of Korea, China and Japan altogether thanks to this exhibition and the forum. Also, it’s the first time for master artisans from the three nations to get together. It will be a great opportunity for them to share the differences in their own distinctive construction styles,” said Oh Seon-hwa, curator of the museum.

“Concerning traditional architecture, there have been no human and academic exchanges among the three nations although they share similar wooden architecture traditions and history,” she said.

The museum said that it owns such rare documents as “Yeonggeon Uigwe” (Construction Reports), containing a detailed account of the intricacies of traditional construction culture. “We are proud to host such an event. Suwon is historically associated with ancient construction, especially being home to Hwaseong Fortress, a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site,” she said.

The curator explained that King Jeongjo (1752-1800) held 11 banquets to cheer up the craftsmen and carpenters, building the fortress from 1794 to 1796. “Such reports testify just how much King Jeongjo cared about the artisans,” she said. The structure was constructed to honor his ill-destined father, Crown Prince Sado, who was trapped in a large rice chest and left to die by the order of his own father King Yeongjo due to a conspiracy by his political opponents.

Korea’s master carpenter Shin Eung-soo, Li Yongge from China and Mitsuo Ogawa from Japan, will take part in the exhibition and forum.

“They all have secrets to the ancient construction story, largely because they are living custodians of the traditional skills of the royal carpenters who mentored them,” she said.

According to the museum, historically the three nations have different patterns of preserving the skills of ancient construction. Korea recorded construction techniques focusing on the structures rather than the master craftsmen during the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910). Japan has transferred secrets to its descendants through books authored by the carpenters’ families during the Edo period (1615-1868) while in China one family dominated royal construction during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Shin is one of the top carpenters who headed the restoration project of Gyeongbok Palace, Gwanghwamun (the main gate of Gyeongbok Palace) and Sungnyemun (National Treasure No. 1). He was a vice-master builder during the restoration work of Bulguk Temple in 1970. He took the helm of a master builder for the first time for the restoration work of the Jangan-mun (Perpetual Peace Gate) at Hwaseong Fortress in 1975. He currently has 30 apprentices under his tutelage.

As a representative of a third-generation palace carpenter, Li has overseen the building and renovation of the old structures at the Palace Museum in Beijing’s Forbidden City. He is the successor of Ma Jinkao, Dai Jiqiu and Zhao Congmao. He joined the restoration works in the Palace Museum in 1975. Since 2000, he has served as head of the department related to the reconstruction of traditional architecture. Li is training 14 young carpenters who recently took up an apprenticeship with him.

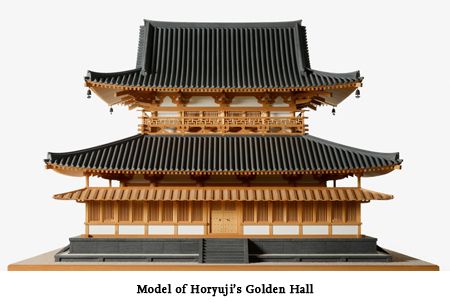

Ogawa is the only disciple that succeeded Nishioka Tsunekazu (1908-1995) who was chief carpenter of the Horyuji Temple. For the first time Ogawa has earned the reputation as an “important intangible heritage” of Japan’s wooden architectural field. He worked as an apprentice to Tsunekazu when he was 22 and subsequently gained complete mastery of the vital construction skills that spurred him to the position of chief carpenter after five years of apprenticeship. He participated in the restoration work of the three-storied pagoda of the Horinji Monastery in Nara, hit by a lightning in 1944. He also rebuilt the Golden Hall and the West Pagoda at Yakushiji Monastery. In 1977 Ogawa founded Ikaruga-Kosha, a temple carpenters’ school, where he is training young carpenters, to pass on the ancient skills learned from his mentor to the next generation.

The museum will also display “Joseon Gyeonggukjeon” (Administrative Code of Joseon) which describes the works of master carpenters of the early Joseon era.

“We hope this occasion will further boost relationship among the three nations and enhance the understanding of traditional construction,” she said.

For more information, visit hsmuseum.suwon.ne.kr. <The Korea Times/Chung Ah-young>