Asia’s Challenge: Baby Boom or Baby Bust

The Philippines stands out in Asia for its high fertility and poverty rates

As Japan’s population shrinks and China grays fast, a battle is shaping up in the Philippines, pitching its demographic and economic future against Catholic orthodoxy. The issue: Fewer babies or more?

A global demographic dichotomy is coming into focus in the Philippines where the Congress, which reconvened tis week, is to vote soon on legislation known as the Reproductive Health Bill, which would enable government clinics to provide contraceptive advice and devices. President Benigno S. Aquino III supports the bill, and for this he’s been denounced by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, representing the celibate hierarchy of a politically powerful church in this majority Catholic country. The issue of government support for contraception has been raised many times over the past four decades, and this bill has been in the works for two years already. Opinion surveys suggest that the majority of Filipinos favor the bill, and Aquino’s current high popularity should help its passage. But opposition remains formidable. The legislature’s primary mission for this session is to pass an annual budget, and the reproductive health bill may have been shifted to the back burner.

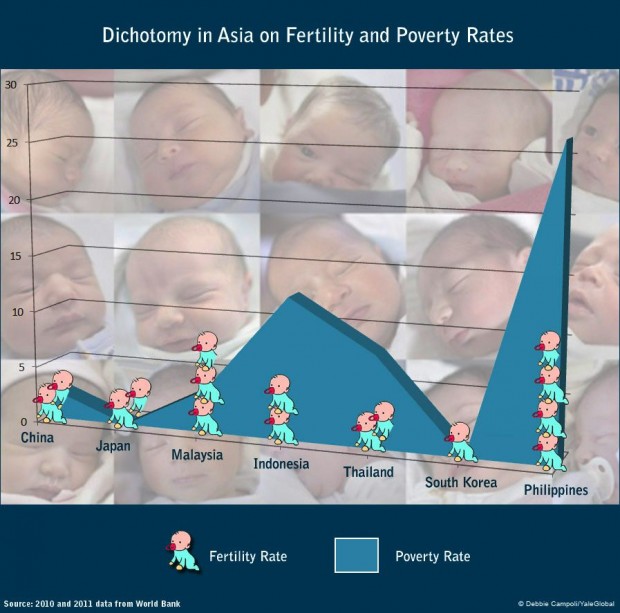

Although contraceptive devices are widely used in the Philippines, particularly by the more prosperous classes, poorer families mostly still have several children, giving the Philippines the highest fertility rate in Asia east of Afghanistan – an average of 3.1 births per woman of fertile age. High population growth – 35 percent of the population is under 15 – is often cited as the reason why per capita income growth in the Philippine has lagged far behind that of neighboring countries such as Thailand and Indonesia.

In opposing the bill Catholics have not merely resorted to papal doctrine, but suggest that easy availability of contraception would lead to a sharp fall in the birth rate similar to countries where the problem now is over-rapid aging. This is an opportunistic argument against enabling all members of society to have access to contraception. But it does have a grain of truth, indicated by the feast to famine changes in fertility elsewhere in East Asia.

All the countries in East Asia with rapid declines in fertility have benefited by enjoying high savings rates and falling dependency ratios. But that is now changing so future growth will be much harder to achieve and several countries face future aging shocks more severe even than Japan’s. The median age of Japan’s population is now 45 and despite Japanese longevity, the total population has begun to decline. South Korea and China will likely be in the same position by 2030 or earlier. Meanwhile the Philippines is struggling to keep economic growth far enough ahead of population to raise living standards significantly.

At the other end of the fertility policy spectrum from the Philippines is China, which has had three decades of its one-child policy, using penalties and forced abortions to reduce its population growth. The crudity of China’s enforcement is emphasized by the fact that its neighbors saw equally steep falls in fertility with no compulsion. For example, Thailand, once mainly rural like China at the start of the one-child policy, achieved an identical fall in fertility simply by handing out condoms and by using humorous advertising to promote sex without procreation. A similar campaign was later used to combat HIV. Indeed, for 40 years, from the 1970s ‘til today, Thailand’s fertility rate has almost exactly paralleled that of China.

China’s fertility rate is now a mere 1.6, far short of the 2.1 needed for long-term stabilization. Without a pick-up, China’s population will start falling within 20 years. As the government becomes more concerned about rapid aging, the one-child policy is likely to be abandoned before long. However, that may do little to raise the fertility rate, and China probably will continue to adhere to the East Asian model of low fertility. Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore and Japan now have levels of 1.0 to 1.4, well below the Western European average of 1.7.

China may well see further decline in fertility because of the gender imbalance – fewer than 9 women for 10 men in for the group aged 5 to 20 years old. Several years ago Shanghai eased one-child implementation, but that made scant difference for a fertility rate recently been reported at just 0.7, probably the lowest in the world.

The consequences of both too many and too few babies show up in dependency ratios – the young and old dependent on those of working age. A higher ratio of young dependents usually correlates with increased poverty. China currently has a low overall ratio of around 38 percent, but this is set to rise to 45 percent by 2030. Thailand is roughly similar. Both nations already have almost static working-age populations. At the other end of the scale, the Philippines dependency ratio is 63 percent – assuming a gradual decline in fertility that would still be 55 percent by 2030.

If there is a middle way between the baby boom and baby bust, it’s provided by Indonesia, which has seen a gradual fall in fertility, now around the long-term stabilization level. Its total population should stop growing in about 30 years.

Projections of median age reveal the challenges ahead. By 2030 the median age will be just 22 in the Philippines, half that of South Korea, 47; China’s will be 43 while Indonesia will be at 35 – the same as China and Thailand today. Thus while today’s problem is the high level of poverty in the Philippines due to high fertility, tomorrow’s problem will be avoiding a decline in living standards in countries with aging populations and declining workforces.

East Asia falls behind Western Europe in fertility rates despite government exhortations in Japan, Korea and Singapore, even some financial inducements to having children. There appears to be no easy answer, but the experience of north European countries plus Australia and New Zealand may provide a guide. France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and all of Scandinavia and the antipodean countries have rates of 1.9 and above, yet all show high female participation in the workforce – not as high as China’s, but higher than Japan and Korea – and strong gender equality laws and practices.

They have in varying degrees job protection and generous leave for pregnant and nursing mothers, government funding of nursery schools, direct child support payments and other measures to reduce the economic opportunity costs of childbearing. They see this as investment in the future workforce, not just welfare cost.

In most of East Asia not only are the opportunity costs of children high, but there’s reluctance on the part of many employed and well educated women to marry and risk submission to male assumptions of superiority. Countries in the West with high fertility rates also have high rates of birth out of wedlock. Women can choose to have babies without choosing a permanent partner. That is not yet socially acceptable in most of East Asia – except, ironically, in the Philippines where some 20 percent of births are out of wedlock, thanks in part to the Catholic Church’s opposition to contraception and a ban on abortions.

All in all, something must give in these Asia’s low-fertility societies if the Catholic bishops are not to be proved partly right on one aspect of the contraception debate. Demographic changes are unpredictable, and fertility may recover without government help or social change. But don’t count on it.

Philip Bowring is a co-founder of Asia Sentinel. This is reprinted with permission from the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization. <The Korea Times/Philip Bowring>