How far can English education go?

For decades, Koreans’ zeal for learning English has been incomparable. Parents spend more than 20 trillion won ($18 billion) each year on private education for primary and secondary school students and about a third goes to English language education, government statistics show. The amount does not include money spent on toddlers, college students and adults.

Businesses hoping to gain from the vast market have popped up and disappeared. But one company has persevered for more than five decades in catering to — and sometimes creating — the demands. It will be no exaggeration to say that the firm has become the history of Korea’s English language education and changed the way Koreans learn the foreign language forever.

Founded in 1961 as Sisa English by Chairman Min Young-bin, a former journalist at an English-language daily, YBM has a foot in every language education business one can imagine — language institutes, an e-learning website, proficiency tests and international schools.

Little known are somewhat unlikely ventures YBM tried but gave up — it used to own a mutual savings and finance company that is now Hyundai Swiss Savings Bank; a cable TV channel, currently SBS Golf; and a record label that later grew into an entertainment company operating the country’s biggest digital music site, MelOn.

Along with the advance of technology, the company was quick to explore new businesses decades before the followers did. The only thing that hampered YBM from moving even faster was the government’s tight grip on the education sector.

When asked what his management philosophy is, Min Sun-shik, the president of YBM and the founder’s son, said after taking a long pause, “I haven’t really thought about it… We try to differentiate from competitors. We do things before others do and the things they wouldn’t do. That’s how we survived.”

The company has so far succeeded in foreseeing future trends, but Min, who received a Ph.D. in business administration from Harvard Business School, is restless to see the industry in decline, without clearly knowing what the next move should be.

“That is truly our big concern,” said Min.

1960s to 1980s: blossoming of English education

In 1961, former journalist Min Young-bin found a publishing house specialized in English language study materials. He later re-named the company after his by-line, Y.B. Min.

In the 1960s when Korea was an impoverished nation just out of war, the medium of studying English was limited to printed publications including magazines, books and dictionaries.

After launching the country’s first magazine for English learners in 1961 and another entertainment-oriented periodical in 1964, YBM published in 1967 “A Handbook of Business English” in response to policies designed to drive exports.

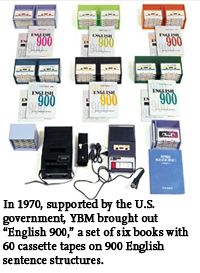

The next decade marked the use of audio and sound in language education. In 1970, supported by the U.S. government, YBM brought out English 900, a set of six books with 60 cassette tapes on 900 English sentence structures.

The popularity of the new medium led YBM to set up a record company, Seoul Record, which initially produced study materials and grew to a major music label.

Seoul Record released an album of Korea’s first dance trio Sobangcha (fire-engine in Korean, literally) and debuted hallyu (Korean wave) celebrity Rain. It was also YBM’s first affiliate to get listed on a stock exchange.

The company did not produce singers on its own and with the decline of compact disk sales, its business dwindled. In the early 2000, SK Telecom, the country’s No. 1 mobile operator, suggested investing tens of billions won for a repertoire of songs that can be played only via its digital music site MelOn.

YBM decided that for such a large sum of money, it would be better to sell the whole record label to SK, which turned it to LOEN Entertainment. LOEN not only sells records but also produces celebrities including teenage singer IU.

The 1980s saw Koreans become serious about English language education. And YBM laid a foundation for the core elements of today’s English language education — proficiency tests, foreign teachers from English-speaking countries, and studying overseas.

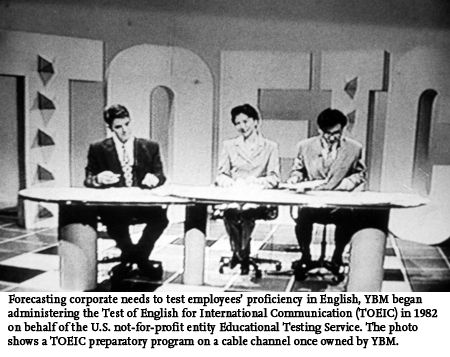

Forecasting the corporate needs to test employees’ proficiency in English, YBM began in 1982 administering the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) on behalf of the U.S. not-for-profit entity Educational Testing Service.

The test would take off nearly two decades later amid globalization efforts after the Asian Financial Crisis between 1997 and 1999. Korea now accounts for 40 percent of the people who take the test worldwide.

“In the 1990s, those who scored more than 900 would be covered by newspapers. The average score was around 430,” Min Sun-shik recalled.

In 1983, YBM opened the first English language school in southern Seoul for teaching communications skills, staffed only by American teachers. Until then the government did not allow foreigners to teach in Korea.

In a partnership with the New Jersey-based ELS Language Centers, YBM set up the institute and brought seven English teachers from the U.S. on teaching visas, the first American teachers to come to Korea on legal visas.

Native-speaking teachers now come from New Zealand and South Africa as well and are found across the country in both public and private schools. Beginning to hire native-speaking teaching assistants in 1995, public schools employed 8,465 foreigners for English language training as of 2010.

Another forward-looking venture was a center set up in 1982 to help people prepare for studying abroad. These advisory businesses would become staples in southern Seoul two decades later on which richer, younger generations relied in order to get admitted to prestigious boarding schools and colleges in English-speaking countries.

“Globalization started in the ’80s. Before that, we weren’t even allowed to hire foreign teachers. Now, anyone can study abroad, but it used to be difficult to get a passport. You had to go to the Korean Central Intelligence Agency and get some training,” said Min.

1990s: Asian financial crisis

The late ’90s marred by the Asian Financial Crisis was difficult time for YBM.

In 1990, the company launched Korea’s third English language daily, Korea Daily, but discontinued it within a year due to difficulties in distribution. And around that time, the founder’s son, Min Sun-shik, took the helm. No one probably could have a better background in business administration education — he had a Ph.D. in the subject from Harvard and a master’s from MIT Sloan School of Management.

Min recalled the financial crisis as “a very painful time” mainly because of two businesses.

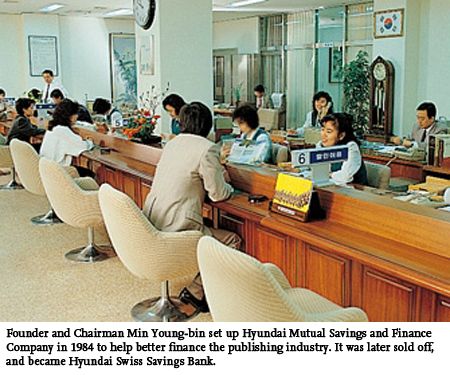

One was Hyundai Mutual Savings and Finance Company set up in 1984. Min said that the publishing business faced high risks, especially delayed the collection of charges. Several publishers hoped to run a short-term investment finance company for better financing, but the government instead recommended a mutual savings and finance company, a smaller body, because the publishing industry wasn’t big enough.

When other publishers pulled back from the plan, YBM, whose founder chaired the association of publishers then, became the sole operator of the financial company that ran well until the financial crisis.

During the crisis, Hyundai’s capital dried up, and a moneylender active in Myeongdong, downtown Seoul, showed interests in buying it. YBM ended up selling it for 1 won. Back then major shareholders had to be responsible for all deposits until three years after it was sold if the buyer couldn’t make up everything.

After the crisis, the government loosened regulations on the secondary banking sector, boosting the demand for the license to operate a savings bank and its price. Mutual savings and financing companies even got a better name “savings bank.” YBM’s mutual savings and finance company is now Hyundai Swiss Savings Bank, which became Korea’s largest savings bank by assets after a series of leading savings banks were closed down in the past couple of years.

Another headache was the cable TV channel that was bought to operate an open university for distance learning.

Because universities give degrees, YBM had to obtain a license from the government. The state-run Korea National Open University was dominating the distance learning market back then.

Considering distance learning channels by the state-run EBS has been immensely popular in the last decade, YBM did think ahead. It launched MY TV on channel 44 on March 1995, but had to be given up in three years.

Min ended up not getting the license for an open university and the TV channel was better to be sold off in the time of crisis. One suitor showed interests, and it turned out to be SK Group. A couple of days after the deal talk, however, Korea entered the bailout program by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and SK backed off, Min said.

The conglomerate later did acquire the channel but during the Kim Dae-jung administration between 1998 and 2003, it was encouraged to sell off non-core affiliates. SK sold the broadcasting company to SBS, which turned it into a popular golf channel.

Post-IMF: the boom

The financial crisis planted in Koreans’ mind a strong need to globalize, making proficiency in English one of the most sought-after skills. Small language schools closed down during the recession, so the time was ripe for YBM, the dominant survivor, to harvest on the business models developed over decades.

The biggest growth was seen in TOEIC. The number of TOEIC test-takers hit the world’s highest in 2001 at 980,000. It would more than double to 2.1 million in 2011, posing great challenges to YBM in handling so many tests.

The post-crisis era saw rapid diversification in teaching methods as well as YBM’s business portfolio.

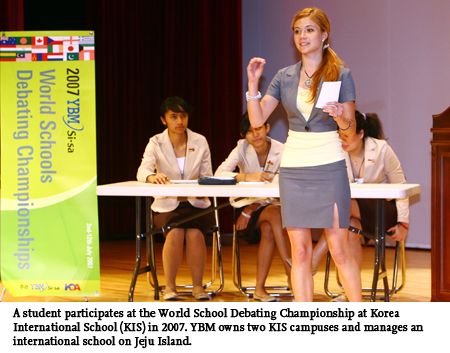

In 2000, YBM added two new significant businesses — it set up an online education affiliate, YBM Sisa.com, and opened the Korea International School (KIS) in Gaepo-dong, southern Seoul.

The school started out in a small building in the wealthy neighborhood with only two classes in each grade, but the demand exploded soon as the words of mouth spread swiftly.

YBM bought a 33,000-square-meter land near Bundang, a popular residential town in Gyeonggi Province, for a second campus. Because the land was originally intended for a foreign language high school, YBM donated two fifths of the land to the government, helping the approval process speed up. The second campus in Pangyo opened in 2006.

“When I visit the school, I feel rewarded. The class that graduated in June achieved an average score for the SAT exam of 2100. That would be within the top 30 of all American high schools,” Min said. The SAT is a critical test for college admissions in the U.S. with the perfect score of 2,400.

He adds that graduates are now at various Ivy-league schools including Harvard and Princeton, except Yale.

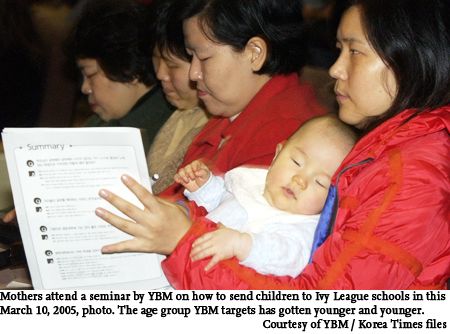

In the meantime, YBM was working on two different strategies — catering to younger learners and entering overseas markets. In 2005, the company opened Appletree, an English school for three-year-old children, some of who are still in diapers.

Unlike many of its competitors, YBM has shunned college preparatory education. While it’s the most lucrative segment, it can also be the most risky — easily swayed by changes in the government’s policies.

“To be honest, we aren’t really good at it or want to do it. We have a very different business culture. Because we didn’t enter college preparatory business, we didn’t rise or fall dramatically,” said Min.

Challenges ahead

After a prosperous decade, Min came to see the growth of the English language education market reaching a plateau.

He sees the demand for teaching to standardized tests remain stable but that for speaking skills is decreasing as most of the young generations speak decent English. And those hoping to speak better English would simply take off a year abroad.

The age group of its customers has gotten younger and younger, so the extremely low birth rate concerns Min.

The print media are gradually sinking. The company was the official distributor of Newsweek and still publishes the National Geography in Korea. Until the early 90s, it had a subscriber of some 200,000. “When I checked it a few days ago, there were some 25,000 subscribers left,” said Min.

Making matters worse, the government wants to beat TOEIC with its own developed English proficiency test, National English Ability Test (NEAT).

Despite challenges, Min wants his current revenue of around 500 billion won to double to 1 trillion won.

“In 10 years, the revenue will have to reach 1 trillion won. Considering the inflation rate in the neighborhood of 3 to 4 percent, if our revenue stays the same, it, in fact, has been chopped to a half,” Min said.

Among a few options, Min sees two possibilities — overseas markets and niche markets although admitting that the latter won’t grow much. YBM has already tried many niches including English language education for ethnic Korean children living in China and the air force.

In China, he saw many business opportunities, but found doing business there wouldn’t be easy because most need licenses from the government, leaving foreigners with little to do. The major part of YBM’s operation in China is business to business services for Korean corporations — helping them to localize by teaching Chinese to Korean expats.

YBM has two ELS-brand language schools in Canada and opened one in Philippines, which didn’t last long because of too many budget-conscious students. The company still keeps there a call center with more than 200 employees who teach Korean students English speaking skills on the telephone. The telephone English teaching program makes some 10 billion won of revenues a year, the president said.

Meanwhile Min sees some potential in Japan, an economic power with a large population that struggles with learning English probably more than Koreans do. “The major shareholders of the world’s two largest language institutes, ELS and Berlitz, are Japanese firms. I think there will be an opportunity in Japan,” said Min.

He knows now is the time that needs creativity of the market the most. Throughout the interview, Min’s frustration with the lack of market freedom in the education sector reverberated.

He had already learned a bitter lesson from the government’s rejection to give out a license for operating an open university. Min recalled that he initially thought getting one would be no problem until he realized it wasn’t possible.

“One of my friends told me that you shouldn’t fight against the government. Our chairman said he was never been in the government license business. He told me that it is extremely difficult to maintain the license, and when I was involved in it, I came to understand what he meant,” said Min.

The latest scandal involving the rich buying nationalities to get their children admitted to foreign schools is also ultimately linked to the government’s regulation. Students initially had to be foreign nationals, dual-passport holders or permanent residents in foreign countries. Or one of the parents had to be a foreign national or to have resided abroad for five years or more.

Under the Roh Moo-hyun administration, rules changed in a way that students’ nationalities do not matter but their parents’ do. In other words, foreign-national students with Korean parents no longer are guaranteed admission to international schools. In the latest scandal, those who obtained foreign nationalities from developing countries such as Guatemala weren’t the students’ but those of their mothers and fathers.

Min said that when a private sector is left alone, it will find what people want and need. “But our society isn’t ready yet for a private business to take responsibility from the beginning to the end. I wonder if under such a mindset, the free competition of the market economy could be sustained,” Min said.

“If there is a good prospect in an industry but with such heavy regulation, who would want to jump on that bandwagon? Let them be regardless they win the mare or lose the halter,” Min said. <The Korea Times/Kim Da-ye>