High-Stakes Drama: The South China Sea Disputes

*Author, Mark J. Valencia is a Research Associate with the Nautilus Institute and can be contacted at mjvalencia@gmail.com.

The latest act in the long-running saga of the South China Sea has seen China moving aggressively to enforce its claim to most of the features of the potentially oil-rich sea while the US ‘rebalanced’ its defense and foreign policy toward Asia. As a partial result of US-China rivalry, ASEAN’s unity and its centrality to security issues are facing a severe crisis. The drama is far from over, writes Mark J. Valencia, and the road to a satisfactory management of the South China Sea conflicts is fraught with peril.

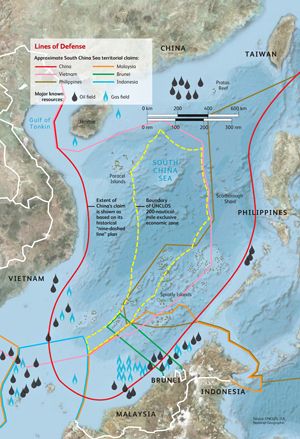

THERE HAVE BEEN numerous significant developments in the South China Sea disputes over the past year.1 At the end of 2011 there was in place a weak and leaking Declaration on Conduct (DoC) for activities in the sea as well as vague and general guidelines for its implementation. The bilateral/multilateral conundrum regarding the process of negotiations between China and ASEAN loomed large. The Philippines was mounting a campaign to get China to clarify its nine-dashed line claim (see map on page 60) and pushing a proposal for a Zone of Peace, Freedom, Friendship and Co-operation designed to separate “disputed” from “non-disputed” areas in the South China Sea. China had warned Vietnam, the Philippines and India (its national oil company ONGC was operating in the sea under license from Vietnam) against exploring for hydrocarbons within its claim line. Yet both ONGC and Forum Energy/Philex Petroleum had announced plans to drill in 2012 in areas claimed by China — the latter on Reed Bank. India had entered the mix not only via its national oil company but by insisting that it has a rightful naval interest in the South China Sea.

Most significant, the US-China rivalry in the region was intensifying, sucking ASEAN and its members into its turbulent political wake. Indeed the disputes had become a new cockpit of China-US competition, distorting and overshadowing the intra-ASEAN and ASEAN-China disputes. The US-China rivalry was driving the issues forward and creating pressure on ASEAN and China to make progress or at least put together a temporary arrangement regarding the disputes.

This paper covers developments from the November 2011 Bali summits through the July 2012 Phnom Penh ASEAN meetings and their immediate aftermath. It summarizes the current political and strategic context, significant developments and the current situation, and then sketches several alternative futures.

The Political And Strategic Context

The tectonic plates of the international political system are inexorably grinding against one another, and the US and China are on opposite sides of the divide — and perhaps history. The US is yesterday’s and today’s sole superpower, but its credibility, legitimacy and ability to enforce its will are fast eroding.2 China’s leaders believe China represents the future, not just in hard power but also in economy, culture and values. Indeed, China’s leaders believe it is China’s destiny to regain its prominence — if not pre-eminence — in the region and perhaps eventually the world.

In classic realist theory, established powers strive to preserve the status quo that assures their position at the top of the hierarchy and view emerging powers as potential threats. Rising powers feel constrained by the status quo and naturally strive to stretch the sinews of the international system. They fear that the dominant power will try to snuff them out before they become an existential threat. These are the primordial political dynamics of the US-China struggle.

Their rivalry is fast becoming a zero-sum game, and both are extremely suspicious of each other’s intentions. Indeed, both countries “see deep dangers and threatening motivations in the policies of the others.”3 It does not help that leadership transitions are under way in both countries, and no candidate for leadership in either country can afford to be seen as weak on such security issues. Some US analysts even see an incipient Chinese “Monroe Doctrine” that would attempt to push the US out of the region.4 Worse, the US and China are tacitly forcing Asian countries to choose between them.

It would appear that the region is now at several tipping points regarding regional security architecture. Key questions include:

• Can ASEAN maintain unity by resolving its internal differences on these issues or is ASEAN unity in security a myth and an impossible dream in an era of competing big power strategic concepts and capabilities?

• Will ASEAN maintain its centrality in its own creations like the East Asia Summit and the ASEAN Regional Forum?5

• Will US-China rivalry dominate these and other ASEAN “Plus” forums?

• Will the US attempt to drive the agenda of these forums and to emphasize negotiations and deliverables as opposed to ASEAN’s more laissez- faire approach?

• Will robust US participation in Asian political and military affairs survive looming defense budget cuts and the coming change of administrations or key personnel?6

The strategic goal of the US in Asia — besides spreading its values and way of life, including to China — is to maintain stability and the status quo by deterring Chinese aggression or coercion against its Asian “allies.” The conceptual intent is to encourage China to buy into existing international law and the order built by the West after World War II. US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said at the June 2012 Shangri-la Dialogue, “If both of us abide by international rules and international order, if both of us can work together to promote peace and prosperity and resolve disputes in this region, then both of us will benefit.”7

Panetta also has said that “the United States will renew its naval power across the Asia-Pacific region and stay ‘vigilant’ in the face of China’s growing military,”8 adding that “the key to that region is to develop a new era of defense co-operation between our countries, one in which our militaries share security burdens in order to advance peace in the Asia-Pacific and around the world.”

However, US reassurance of its allies and friends may have emboldened some to confront China. Further, US attempts to control regional institutions are likely to be perceived by some Southeast Asian countries as upsetting an already delicate geopolitical balance. For them, how the US behaves regarding the South China Sea disputes will say quite a bit about the future geopolitical environment.

China basically believes that Southeast Asian claimants to various islands are nibbling away at its legacy and rightful ownership of islands and resources in the South China Sea and that they are colluding with the US against China.

Moreover, China is gaining confidence as its economic and military might grow. However, China is facing a strategic dilemma in that its efforts to defend its maritime claims and interests are conflicting with its policy to improve relations with Southeast Asian countries. Its goal is to restore its “tarnished image in East Asia and to reduce the rationale for a more active US role there.” It recognizes that Western “soft power”9 has an advantage in the region and that it needs to “fight back” in kind.10

But China also continues to hint at its hard power. Indeed, Defense Ministry spokesman Geng Yansheng has said that the armed forces have vowed to “fulfill their duty” to safeguard China’s territory, rights and interests in the South China Sea.11 China is rapidly developing the unmanned aerial vehicles and littoral combat ships that it would need to confront the US Navy. Meanwhile, Chinese policy-makers “talk openly about their intent to oppose American unipolarity, revise the global order and command a greater share of global prestige and influence.”12

The current US “rebalancing” in Asia has disturbed Beijing’s military strategic planning.13 One Chinese strategic analyst sees the US balancing as a cover for “forging its alliances into the first island chain … while retreating its own military to the second island chain.” China’s leaders increasingly view the US alliance system in Asia as a relic of the Cold War,14 and they argue that the trend in Asia is toward peace and co-operation, not military alliance-building and the continuation of Cold War thinking.15

Some US conservatives argue that China is seeking to take advantage of the US preoccupation with this November’s elections to push hard in the South China Sea.16 Others say that China seeks to advance its cause incrementally, its policy-makers “extending and strengthening their influence wherever possible, while working quietly to weaken Washington’s position.”17

China clearly realizes that the US is not going to go away on its own nor reduce the pressure of its presence in the region. Indeed, contrary to China’s characterization of it as an “outside power,” the US says it is part of the Pacific family of nations and that it has a valid interest in freedom of navigation and access to the international commons in the South China Sea. The eventual result may be the pitting of China’s “denial of access” against US “assurance of access.” However, some Chinese strategists have warned their government that the South China Sea could become a trap that will divert and waste China’s economic and political capital.

One possibility — though unlikely — is the US and China agreeing to “deal with one another as equals.”18 Some suggest a grand bargain “centered around a Sino-US condominium — with the (tacit) approval of other major powers such as India, Japan and Australia.”19 Such an order would “establish principles or ‘red lines’ that the US and China would agree not to cross — most notably a guarantee not to use force without the other’s permission, or [except] in clear self-defense.” The fundamental challenge for the US is to discourage China’s aggressiveness while convincing China that the US is not its enemy — a rather delicate task. One interesting twist has been to argue that the US presence provides reassurance to smaller nations so that China can continue its rise without appearing to threaten them. Others suggest that China’s increasing dependence on raw material imports will inevitably lead it to challenge the US role in Asia, resulting in security competition.

US-China military relations are already poor and deteriorating. “The PLA is quite transparent about intentions, but opaque about their capabilities. The United States is the reverse … transparent about capabilities but ambiguous about intentions,” as one analyst put it.20 The two have been unable to agree even on an agenda for military talks. China insists that the US stop arms sales to Taiwan, cease “close-in” maritime and aerial surveillance of China, and remove restrictions on exporting American military technology to China.21 Although their May Strategic and Security Dialogue was marred by the case of rights activist Chen Guangcheng, who sought refuge in the US Embassy in Beijing and eventually was allowed to resettle in New York, the defense chiefs of the two countries subsequently met in Washington and US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta visited China.22 It was hoped that these meetings would lead to a lowering of tension between the two powers. But this appears not to have followed.

The Here And Now

The current situation raises more questions than answers. The US is telling China to play by the rules, i.e. the law of the sea, although it alone among major powers has not itself ratified the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Despite its denials and claims to neutrality, the US has taken a position on the South China Sea issues on the side of the ASEAN claimants. For example, it supports multilateral rather than bilateral negotiations, resolution of the disputes according to UNCLOS, and claims to sea areas only from land and legal islands… all contrary to China’s positions.23

The US move to station troops in Darwin in northern Australia — which some believe will also involve US warships, intelligence gathering platforms and maybe even B-52 bombers — unsettled the region. Indonesia is wary of it because it puts it geopolitically in the middle, between the US and China. In May, Panetta visited Vietnam and Cam Ranh Bay and discussed renewing an agreement on Vietnamese commercial repairs to non-combat UN Navy ships. The timing of the visit indicated that Vietnam believes the US has a legitimate interest in the maritime affairs of the South China Sea.

The Philippines publicly supported the US “pivot” or “rebalancing,” which is now Washington’s preferred term. According to US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Kurt Campbell, “We are writing a new chapter in our relationship [with the Philippines] and turning the page from a legacy of paternalism to a partnership of equals.”24 The emphasis of US military assistance will be on maritime security.25 Japan, South Korea and Australia are also helping the Philippines establish a “minimum credible defense.” Meanwhile, the position of other ASEAN members regarding the US pivot seems to be in flux.

Ratcheting up the pressure, the US told ASEAN that it must come up with a clear common position on a Code of Conduct (CoC) in the South China Sea. This will be very difficult. The main focus now is on negotiating a code. There is a lot riding on the success of the venture — such as ASEAN centrality in security paradigms for the region, ASEAN solidarity and the tone and tenor of ASEAN-China relations. A robust code would also relieve some pressure from the US on both China and ASEAN, and diminish — but certainly not eliminate — the opportunity for US-China political conflict. But first the parties have to negotiate a text that is both acceptable to all and effective in managing the conflicts — a rather tall order given the diversity of interests of the 10 ASEAN members (only Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam are claimants) and those of China. Some pressure is helpful — but too much pressure could split ASEAN. If the ASEAN claimants continue to confront China, ASEAN could divide on this issue — as became evident when the Phnom Penh ministerial meetings in July could not reach consensus over the South China Sea issue and failed to issue a communiqué for the first time in the association’s 45-year history.

Meanwhile, China continued to criticize the US and to defend its South China Sea claims and actions. China is convinced that it will result in increased US meddling in the region’s political affairs. In particular, China opposes any US attempt to intervene in the South China Sea disputes. And it denies that it is or ever will be a threat to freedom of navigation. Yi Xianliang, Deputy Director General of China’s Department of Boundary and Ocean Affairs in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, turned US statements on their head by saying, “Washington’s role and functions in the South China Sea should adhere to international law and it should play by the rules.” Strategically, China appears to be waging a soft-power war while it develops its hard-power capabilities. Demonstrating its soft power, China established a $472 million maritime co-operation fund to develop a “maritime connection network” with Southeast Asian nations. It also continued to meet with ASEAN to try to implement the DoC.

Nevertheless, one cannot completely rule out a military confrontation, particularly with Vietnam, which is more diplomatically isolated than the Philippines. The growing concern in China is that its historic claim to most of the South China Sea is weak in the context of modern international law,26 making the disputes more dangerous and subject to power politics.

China apparently lobbied with host Cambodia to keep the South China Sea off the agenda of the April ASEAN Summit. Chinese President Hu Jintao made the first state visit to Cambodia in 12 years just prior to the summit. It appeared that his efforts were successful when Cambodia reportedly removed the topic from the agenda, much to the frustration of the Philippines and Vietnam, which have borne the brunt of China’s assertiveness on this issue. “Cambodia does not want to use ASEAN to square up against another country,” said information minister Khieu Kanharith.27 Hu said that while China supported a CoC he did not want the issue pushed “too fast” or for it to be “internationalized” in a way that would threaten regional stability.28

However, after a few days the item mysteriously reappeared. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen angrily denied that there was a rift in ASEAN or that Cambodia had been influenced by any nation in setting the agenda as host and ASEAN Chair.29 A subsequent report said that China’s leadership essentially invited itself to Cambodia in an attempt to influence both Cambodia and ASEAN regarding the South China Sea.30

China declined to send senior officials to the Shangri-la Dialogue in June in Singapore, citing domestic scheduling conflicts. Others speculated that China did not want to discuss the South China Sea dispute in a multilateral setting.31 Meanwhile, China continued to promote its nine-dashed line historic claim in both word and deed. It declared its annual unilateral ban on fishing north of 12 degrees latitude in the South China Sea from May 16 to Aug. 1 and arrested Vietnamese fishing boats and crews near the disputed Paracel Islands on the first day of its ban. The 2012 ban included around Scarborough Shoal, which China disputes with the Philippines. It denied that Chinese vessels and a navy ship had “invaded” Philippine waters.32 It protested a publicly announced Philippine plan to explore for petroleum in “Areas 3 and 4,” which are near Reed Bank but well within Philippine claimed waters. And it criticized US-Philippines joint military drills near disputed areas as potentially destabilizing. It also warned Vietnam and the Philippines not to hold such military exercises and patrols in waters that it claims.

Meanwhile, the International Crisis Group blamed some of China’s assertive behavior on a lack of co-ordination and bureaucratic competition among 11 state ministries and their enforcement agencies with mandates to manage various aspects of the South China Sea.33 It concluded that China should be prodded to exert control over these agencies. The top “dragons” are the China Coast Guard (public security), the Maritime Safety Administration (transport), the Fisheries Law Enforcement Command (agriculture), the State Oceanic Administration (land and resources) and Customs. Some argue that China is using its fishing fleet as an unofficial marine auxiliary, provoking confrontation when desired.

China also advanced its capabilities to find and harvest petroleum in the South China Sea, taking delivery of a deep-water marine geophysics and geology research vessel capable of drilling 600 meters into the seabed in 3,000 meters of water. And the China National Offshore Oil Corporation began drilling its first deep-sea well in the northern South China Sea. So far China’s only deep-water find had been the Liwan gas field, 300 kilometers south of Hong Kong, discovered by Husky Oil in 2006. This was a major find and piqued the interest of China’s government and industry in the South China Sea’s deep-water potential. This proven capability also enhances the attractiveness of its joint development proposals for disputed areas.

The Role of ASEAN

ASEAN has long been dismissed by realists and skeptics as nothing but a talking shop with no political clout. But with Washington’s rebalancing and China’s rise, it has assumed new strategic importance, and there is an ongoing US-China contest for the hearts and minds of the association and its members. ASEAN has no official position on the South China Sea disputes, and even the DoC was an agreement between ASEAN member states and China, not between China and ASEAN as an entity. ASEAN’s goal is to seek consensus among its members, claimants and non-claimants alike, as well as with China on a Code of Conduct that would implement the Declaration on Conduct according to the agreed guidelines. But progress has been slow. Neither the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Siam Reap in January 2012 nor the following ASEAN-China meeting in Beijing produced significant advances. Differences between ASEAN claimants and non-claimants retarded the process.

Meanwhile, pressure on ASEAN to reach a consensus, both from within and from without, continued to grow. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called again on ASEAN and China to reach consensus on a binding CoC.34 And Joseph Yousano Yun, US Principle Deputy Assistant on Security for East Asia and the Pacific, pushed for a legally binding code at the 25th ASEAN-US Dialogue in late May.

With US backing, ASEAN claimants seem to have found new confidence in dealing with China. Indeed, some claimants may be more assertive and even take riskier actions than they otherwise would, thus increasing instability in the South China Sea. ASEAN’s tried and true method of decision-making based on consensus, consultation, and proceeding in a step-by-step manner, while previously a successful method of conflict prevention, may not be appropriate for the tasks ahead. Moreover, ASEAN claimants need to resolve their own differences in the South China Sea so they can present a united front to China.

The future of the process is uncertain given the leadership lineup in ASEAN: Cambodia (2012), Brunei (2013), Myanmar (2014) and Laos (2015). All except Brunei are non-claimants, thus this issue may not be a priority for them. Although ASEAN has become adept at hedging and balancing in this new “great game,” its diplomatic skills and style are certainly being tested.

It was little surprise that discord boiled over at the April ASEAN summit in Phnom Penh. The fireworks began when ASEAN Secretary General Surin Pitsuwan announced that China might be invited to participate in the drafting of a CoC. Philippine Foreign Minister Albert Del Rosario argued that ASEAN centrality would be lost unless ASEAN first reached a consensus on a code among its members, and then and only then, negotiated with China. Its position was supported by Thailand and Vietnam. Indonesia favored involving China at the beginning.

In any case, China poured cold water on this sequencing, repeating that it would only negotiate bilaterally with each claimant. The Philippines went so far as to threaten to block consensus on the issue if ASEAN pushed for approaching China from the beginning. Given the adamancy of the Philippines, the rest reportedly agreed to go along, although there were indications that back channels would be used to provide China an opportunity for input to the draft code as it develops. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei said that “China must take part in discussions and negotiations on the crafting of the CoC before it is finalized and presented.”35 Moreover, China wants these discussions to be solely with ASEAN claimants and not with ASEAN as a whole.

The next hurdle was the Philippines’ insistence that the code include its proposal to separate disputed from non-disputed areas, a rather formidable task. Indeed, this proposal lacks ASEAN support and thus seems dead in the water. The ASEAN countries were also divided on whether or not to include a dispute settlement mechanism in the code (or perhaps to establish a separate forum for this purpose) and an administrative structure to implement it, as the Philippines proposed. Supposedly such a mechanism was rejected due to Chinese pressure.36

Other issues that might be stumbling blocks include the geographic scope of the code — whether to encompass the Chinese-occupied, Vietnam-claimed Paracels or not — and whether to ban new construction on already occupied features. At the conclusion of the April ASEAN meeting, the ASEAN leaders were only able to issue a rather weak statement promising to intensify efforts to negotiate a code and to implement the 2002 DoC according to the 2011 agreed guidelines. Putting a positive spin on the outcome, Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa said, “The big picture is the one that must not be lost. Namely that in contrast to the recent past, now we have a situation where all are basically rushing and competing to get the Code of Conduct off the ground.”37 The meeting of the ASEAN Senior Officials’ Meeting Working Group on the code of conduct in late May supposedly produced an agreed draft outline of elements of a code to be submitted to the July ASEAN foreign ministers meeting for a final decision.38 But that meeting ended without a consensus and with deep divisions.

Some observers think China may actually support a slow process culminating in a weak CoC because it excludes the US from the negotiations and it can play for time and exploit differences within ASEAN. China proposed setting up a 10-member group of experts and prominent statesmen to help move the process forward. But Vietnam and the Philippines rejected the idea outright.39 Nevertheless, Surin said that the discussions were moving in the right direction and that “it’s very important to reassure the world that we can manage our differences.”40 ASEAN set a tentative deadline to reach an agreement among itself by July 2012 when Thailand was to become the ASEAN-China co-ordinator.41 That deadline passed with no agreement.

The Scarborough Shoal Incident

The Scarborough Shoal dispute erupted on April 10, 2012 when Philippine naval personnel forcefully boarded and inspected Chinese fishing boats and tried to arrest their crew for violating Philippine laws by harvesting coral, giant clams and live sharks. They were prevented from doing so by Chinese fisheries enforcement vessels and a standoff ensued.

The China-Philippines sovereignty spat over the Scarborough Shoal has roots that run deep and are even primal, comprising rising nationalism and the setting of political and legal precedents, as well as indirectly involving the US-China rivalry.

Access to resources played a role in this particular incident. But this was not the prime progenitor. The real issues are the political precedents and leverage that may be established.42 To be fair, the Philippines was having political déjà vu after having physically lost Mischief Reef — well within its claimed exclusive economic zone (EEZ) — to China beginning with its occupation by China in 1994. Because the US and the Philippines are military allies, and the Philippines publicly appealed to the US for support,43 the Scarborough Shoal incident brought the two great powers face to face, at least behind the scenes. The US repsonse was very cautious, as was that of ASEAN, and the Philippines was disappointed — some say politically “orphaned” by the lack of strong US and ASEAN support.

In sum, diplomatic efforts to resolve the issue were essentially unsuccessful. But tension gradually subsided as cooler heads prevailed. Apparently the parties agreed to allow the dispute to just fade away without resolution. This vague outcome was not good

for the region and probably means that there will be more and worse confrontations to come — there or elsewhere.

The Run-Up to the Phnom Penh Fiasco

In late June, China’s national oil company, CNOOC, startled the region by offering nine oil blocks for bidding by foreign companies on Vietnam’s claimed continental shelf and well within its 200-mile EEZ. This was a major new development because the company had previously been unable to get government approval to initiate operations in such a disputed area.44

The offering includes large parts of blocks that Vietnam has already leased to major oil companies — America’s Exxon Mobil, Russia’s Gazprom and India’s ONGC. ONGC subsequently relinquished its concession having spent over $50 million and paid an exit fee of $1.5 million saying the project was not “commercially viable.”45 But when Vietnam offered new data that made the area look more attractive, ONGC did a volte-face and will continue to explore block 128.46

China’s action outraged Vietnam. It vigorously protested and anti-China demonstrations broke out in Hanoi. Vietnam has asked international oil companies not to bid for the Chinese-offered blocks, warning that it “will not allow any implementation” of exploration there.47

The action appeared to confirm that China claims everything within its nine-dashed historic line. “Everything” means islands, reefs, submerged features, seabed, water column and all resources — perhaps even the air space above. Many countries and analysts were hoping that China was claiming only the islands and reefs within this line and perhaps 200 nautical mile EEZs and continental shelves from some legal islands. Now China’s claim is no longer ambiguous but plain for all who want to see it. Adding an exclamation point, China also sent “battle-ready” ship and air patrols to defend its Scarborough Shoal claim.48 A future mission could well bring a Chinese military presence to Vietnam’s continental shelf.

China appeared to be responding to the passing of the Vietnamese Law of the Sea by the National Assembly, which among other items formally places the Paracels and Spratlys under Vietnam’s sovereignty. Vietnam also allowed a port visit by a US Navy, Scripps Institute-operated oceanographic vessel, which China viewed as a provocation,49 presumably because it had conducted “research” in waters that China claims without its consent. China accused Vietnam of violating the DoC and then established a prefectural-level “city” called Sansha on Woody Island to administer the Paracels, Macclesfield Bank/Scarborough Shoal and the Spratlys.

Perhaps China’s position on the South China Sea is that there is no agreed boundary in that area and thus the area is in dispute and no party should take unilateral action. While China can make arguments regarding “historic waters or historic rights,” they are a reach, and likely to be rejected and even ridiculed by politicians and analysts alike. Worse, “historic waters” is a politically loaded term that traditionally refers to a country’s internal waters in which there is no freedom of navigation. This is a prime concern of the US — that China may one day try to enforce such a regime in the South China Sea. The US insists that unimpeded commerce is one of its national interests.

Politically, China stepped right into the US political “wheelhouse” and Washington is likely to gain considerable advantage with some Southeast Asian nations because of it. Absent a plausible explanation or modification of China’s position, the situation has reached a new level of concern. China seems to have chosen not to heed the sensitivities of ASEAN or US admonishments to accept and abide by the existing order and international law. It apparently will proceed unilaterally in implementing and enforcing its historic claim and refusing third-party adjudication, arbitration or conciliation.

As Secretary Clinton prepared to attend the July ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), she and Campbell, her deputy for East Asia, publicly built up their foray into Southeast Asia. In Campbell’s words, “Washington plans to make its presence known in the region” during Clinton’s visit. In her statement in advance of her trip Clinton said, “The United States is a resident Pacific power,”50 a term intended to indicate that the US is staying put in the region. Given the timing and the general US position on the South China Sea disputes, China’s actions were seen as a diplomatic slap in the face.

Obviously this development will make agreement on a binding CoC with a dispute-settlement mechanism much more difficult, if not impossible. Indeed, it appears to set China on a collision course with Vietnam, much of ASEAN and Western-based customary international law. It is also likely to precipitate a political and military lurch by some ASEAN members towards the US.

The Phnom Penh fiasco

In mid-July, ASEAN convened its scheduled meetings in Phnom Penh: the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting and the ARF. They were an unmitigated disaster due to sharp internal differences.

For the first time in its 45-year history, ASEAN failed to agree on even a joint communiqué at the end of the ministers’ meeting. The meetings foundered on the South China Sea issue, reflecting deep divisions among the members. The deal-breaker was the Philippines’ insistence (with the backing of Vietnam) on including a reference to its recent confrontation with China at Scarborough Shoal, and 2012 ASEAN Chair Cambodia’s decision not to issue a statement rather than include such a reference.51

Surin said the outcome and failure to issue a statement was “very disappointing,” a sentiment echoed by Vietnam’s Foreign Minister Pham Binh Minh.52 Indonesia’s Marty Natalegawa — who had tried to bridge the gaps — said the outcome was “irresponsible.” Philippine Foreign Minister Del Rosario said that the impasse on the statement and the CoC was because of Cambodia’s recalcitrance and “pressure, duplicity, and intimidation” by China.53 Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi denied influencing Cambodia and said (unhelpfully) that there was “no dispute” about China’s sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal.54 He urged the Philippine side “to face the facts about the Huanyan Island [Scarborough Shoal] incident squarely, and not to make trouble.”55 Del Rosario denied Philippine responsibility, saying that “we simply wanted the fact that we discussed the issue [to be] reflected in the joint communiqué, no more, no less.”56

Cambodia insisted that it had not been influenced by any nation and had “taken a position of principle. We are not a tribunal to adjudicate who is right who is wrong.”57 Nevertheless, the shadow of China loomed large over Cambodia’s decision.

Putting the best face on the situation, Surin called the failure a “hiccup.” But analysts considered it more like a spasm or even a seizure. “What this indicates is that China has managed to break [ASEAN’s] insulation and influence one particular country,” said Carlyle Thayer, an Australia-based analyst.58 The event will likely “poison ASEAN proceedings from now until November when the next round of ASEAN and related summits are scheduled in Phnom Penh,” Thayer added.59

Another analyst said, “To show solidarity, it is important to remind China that this is a vital issue for ASEAN and that ASEAN members who are not parties to the dispute share the concerns of their neighbors who are.”60 After a day to ponder the results and next steps, Natalegawa said, “I am even more determined to push for the CoC.”61 But Yang said China would only negotiate when “conditions” are ripe.62

The elephant in the room, of course, was the US-China rivalry. ASEAN had agreed among itself on the elements of a CoC and was prepared to begin negotiating with China.63 The ASEAN agreed elements establish a dispute-resolution mechanism that first uses the ASEAN High Council in the Treaty of Amity and Co-operation (to which China has acceded),64 and failing that the dispute settlement mechanisms of international law, including UNCLOS.

Although China warned nations not to bring up its disputes with the Philippines and Vietnam at the ARF,65 the US and China did not clash as feared, at least in public. Indeed Clinton emphasized Sino-American co-operation in “everything from disaster relief to tiger protection.”66 Lost in the glare of the South China Sea issues, the expected signing of the protocol for the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapons Free Zone was postponed due to reservations from the nuclear powers. France and the UK said the definition of the zone was problematic, while Russia said it had concerns regarding freedom of navigation. The US refused to reveal its reservations. But China said the defined zone might affect its sovereignty over its territory as well as its claimed EEZ and continental shelf.67

Just as the ASEAN Phnom Penh meetings were getting under way, three Chinese fisheries patrol boats entered Japanese claimed waters around the Senkaku/Diaoyutai islands in the East China Sea, drawing an immediate protest from Japan.68 A senior Chinese diplomat said that the issue is “extremely important, as the whole of Chinese society is closely watching for the possible repercussions on bilateral ties.”69 Indeed, Japan recalled its ambassador to Beijing for consultations because of the dispute. Meanwhile, a Japanese senior official said, “Japan will continue to play an active role in helping ASEAN members create maritime rules in the South China Sea. In so doing, of course, the East China Sea is on our mind.” Japan also announced a special ASEAN-Japan summit to strengthen maritime security co-operation.70 Sending another aggressive signal, China appointed the famously hawkish Wang Dengping as political commissar of the South Sea Fleet, a post he had earlier assumed over the North Sea Fleet.71 In early July, ASEAN navies held their first ever maritime security information-sharing exercise.

The fallout of the debacle was not pretty. Although China had denied it was to blame for ASEAN’s failure to issue a communiqué,72 Yang publicly thanked Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen for supporting China’s “core interest.”73 Then China again warned the Philippines against offering oil exploration contracts in areas claimed by China, including on the Reed Bank. In this light, China’s offering of concessions on Vietnam’s claimed territory took on new significance.74

State news agency Xinhua accused the US of “meddling” in the South China Sea disputes.75 To be sure, the US did state its position on the issues and essentially encouraged ASEAN to stand up to China. Also, and much to China’s chagrin, the US administration increased its attempts behind the scenes to press regional countries on the issue and tried to influence the content of the code.

China’s present strategy seems to be to assert sovereignty through civilian actors while adopting a less abrasive military posture. But it also appears that some more aggressive actions are not random but calculated confrontations with the objective of forcing a resolution of some disputes. The situation is thus quite dire and could get worse. If China interferes physically with companies trying to explore for oil under concessions granted by Vietnam or the Philippines, a violent confrontation could well ensue.

The South China Sea disputes were supposed to be — or could have been — an opportunity for China to solve problems responsibly with its neighbors as well as a test of ASEAN’s ability to work together on security issues. Both opportunities were lost. Given the serious implications, China’s action begs several questions: Why is China doing this at this time? Does it have something to do with its leadership transition? Is it a sign that a nationalist military faction has gained more power? Or has China’s leadership decided that the die is cast and it might as well show its hand? Whatever the motives, the move has set the region on edge. China, of course, has the right not only to rise but to try to alter the regional and international order in its favor, just as other nations including the United States have done before it. This recent action seems to be an indication that this is precisely what China intends to do.

Alternative Futures

There are several ways in which this political drama could unfold.76 In perhaps the worst scenario from an ASEAN perspective, the US-China rivalry will feed upon itself, becoming a serious ideological and political struggle dominating the regional agenda, splitting ASEAN and subordinating ASEAN centrality. This would leave the South China Sea disputes to fester and tensions would wax and wane in action/reaction dynamics. International oil companies would shy away and exploration remain in limbo.

The preferred scenario for ASEAN would be one in which a robust and binding CoC is agreed and implemented — not only by ASEAN, but by China as well. This would remove one opportunity for US-China conflict and reaffirm ASEAN’s political competence and centrality. The US and other powers active in the region would accede to the code. Not only would this lead to an era of peace and stability in the South China Sea, but the claimants would find a way to encourage hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation in the area — perhaps through joint development. A non-mutually exclusive alternative proposed by the Philippines is to jointly declare at least the islands as international marine reserves.77 In this scenario, everyone lives happily ever after — or at least until the next political imbroglio draws in outside powers.

Neither of these scenarios is likely, and the reality will be somewhere in between. The disputes can be managed but probably not resolved — at least in the foreseeable future. Talks are likely to drag on both within ASEAN and between it and China — and diplomatic vitriol and tensions will ebb and flow. ASEAN can try to ensure that the reality is closer to its preferred outcome by trying to manage the US-China rivalry without obviously siding with either protagonist. This will not be easy but it may be the key to preserving ASEAN unity on this issue. As China’s military might grows and the US steps up its political and military involvement in the region, hard choices need to be made and the window of opportunity for a peaceful settlement of the South China Sea disputes is closing. ASEAN should be proactive, take a coherent and balanced approach and prepare for crisis management.78

Given the US-China political competition for the hearts and minds of ASEAN and its members, international opprobrium will be the most effective enforcement tool. One international legal option is to agree to bring breaches of a code to the UN’s International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) established by UNCLOS. All claimants have ratified UNCLOS and thus have access to its dispute-resolution mechanisms. Although these provisions do not apply to sovereignty disputes over territory like islands and rocks such as Scarborough Shoal, the tribunal could address questions of whether particular features are legal islands theoretically entitled to continental shelves and 200-nautical-mile EEZs, or are just rocks entitled only to a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. But China’s vague nine-dashed line historical claim that may encompass most of the South China Sea is not directly supported by the convention and is based on discovery, historic use and legal principles not specified in the convention, making the use of ITLOS problematic.

The International Court of Justice could decide the ownership of the features, but China is unalterably opposed to “internationalization” of the dispute, including using the ICJ, and even some ASEAN claimants such as Malaysia are not enamored, having had previous negative experiences with it. Indeed, international legal approaches — despite the Philippines’ preference for them — would likely be a last resort, if that. Regional processes and mechanisms are likely to be favored by China and some members of ASEAN.

The establishment of a strong code and its successful implementation are a significant challenge for the region. But the situation also provides an opportunity. ASEAN unity has its back against the wall, and China’s self-proclaimed “peaceful” rise is also at stake. The parties can demonstrate to the world that they can resolve their problems by themselves without involving outside powers or mechanisms. Not only would this preserve at least a semblance of ASEAN centrality in regional security management but it would also offer some proof for China’s peaceful rise. What is needed now is a regional solution to a regional problem at a high diplomatic level. It was fortuitous that at the time of writing Marty Natalegawa had embarked on a diplomatic odyssey around the region to salvage the situation. On July 20, the ASEAN foreign ministers issued a statement through Cambodian Foreign Minister Nor of “six-point” principles on the South China Sea. They reaffirmed their commitment to implement the DoC and to use its guidelines to do so. They underscored their effort to use self-restraint and avoid force in working on the peaceful resolution of the disputes according to international law and the Law of the Sea. Negotiations on the disputes would be consistent with the Bali Treaty of Amity and Co-operation and the ASEAN Charter. In other words, there was nothing new and they have not even formally approached China yet on the CoC.

Stirring the pot even more, on Aug. 3 the US State Department issued a statement criticizing China’s “upgrading of the administrative level of Sansha City and its establishment of a new military garrison there covering disputed areas of the South China Sea.”79 China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded the next day, reiterating its “indisputable sovereignty over the South China Sea islands and adjacent waters” as well as its right to administer it as it sees fit. More significantly, it criticized other countries for violating the DoC and warned that “while being open to discussing a CoC with ASEAN countries, China believes that all parties concerned must act in strict accordance with the DoC to create the necessary conditions and atmosphere for the discussion of COC.”80 This sounds as if China is having second thoughts about negotiating a CoC, especially if the US continues to “meddle.”

Stay tuned in for the next act in this fascinating political drama. <Global Asia/Mark J. Valencia>

NOTES

1 Mark J. Valencia, Diplomatic drama in the South China Sea, Global Asia, v. 6, No. 8, Fall 2011, pp. 66-71; The South China Sea: Fascinating Diplomatic Theater, Act II, Paper presented to the MIMA Conference on the South China Sea: Recent Developments and Implications for Dispute Resolution, Dec. 12-13, 2011.

2 Kang Choi, A thought on American foreign policy in East Asia, PacNet Newsletter, May 15, 2012.

3 Kurt Campbell interview, IANS, April 17, 2012.

4 Stephen M. Walt, “Dealing with a Chinese Monroe Doctrine,” The New York Times, May 2, 2012.

5 “This perception of ASEAN’s ability and mechanisms to manage our own differences in the region is the centerpiece of the regional architecture. As the host of the ASEAN Regional Forum, which is a primary forum for political insecurity and strategic discussion. I think we need to send out that signal that we can manage and that we can co-ordinate and co-operate in order to resolve our differences,” Surin Pitsuwan, ASEAN Secretary General, quoted in “Brunei’s Role in ASEAN hailed,” Borneo Bulletin, April 3, 2012.

6 Liz Neisloss, “US defense secretary announces new strategy with Asia,” cnn.com, June 2, 2012.

7 Ralph Cossa, PacNet.com, June 6, 2012.

8 “US to renew naval power in Asia-Pacific:” Panetta, www.channelnewsasia.com, May 29, 2012.

9 Nick Otten, “All quiet in the South China Sea,” Foreign Affairs, March 26, 2012.

10 Joseph S. Nye, “Why China is weak on soft power,” The New York Times, Jan. 17, 2012.

11 “China’s military makes solemn vow on territory, South China Sea in particular,” The Diplomat, April 28, 2012.

12 Paul Miller, “How dangerous is the world? Part II,” Shadow Government, Dec. 16, 2011.

13 “What Is Causing South Sea Standoffs — Analysis,” Eurasia Review, Jan. 5, 2012.

14 Ibid.

15 “China says it’s wary of US plan to focus on Pacific military power,” cnn.com, June 4, 2012; “China throws book but Carr praises with chapter and nerve,” smh.com.au, May 21, 2012.

16 “Philippines looks to US treaty in territorial dispute with China,” www.voanews.com, May 23, 2012.

17 Afron Friedberg, “US and China vie for supremacy in the Pacific,” The National, April 20,2012.

18 Hugh White, “China’s choices and ours,” eastasiaforum.org, May 7, 2012.

19 Jochen Prantl, “Five principles for a New Security Order in the Asia Pacific,” PacNet Newsletter 38, June 18, 2012.

20 Daniel W. Drezner, “What I learned about Sino-American relations yesterday,” drezner.foreignpolicy.com, May 2012.

21 Jane Perlez, “Unease mounting, China and US to open military talks,” The New York Times, May 1, 2012.

22 “Chinese defence minister in crucial tour of US,” China Daily, May 7, 2012.

23 Pia Lee-Brago, “China slams Clinton’s remarks on South China Sea row,” The Philippine Star, May 29, 2012.

24 “US-Philippine relations,” voa.gov, Feb. 26, 2012.

25 Pia Lee-Brago, “US military aid shifts to Phl maritime security,” The Philippine Star, Feb. 13, 2012; Joint Statement of the Philippines-United States Ministerial Dialogue.

26 Jose Katigbak, “Talks to endanger China claims — study,” The Philippine Star, May 6, 2012; Robert Beckman, “Geopolitics, international law and the South China Sea,” paper presented to The Trilateral Commission 2012 Tokyo Plenary Meeting, April 21-22, 2012.

27 Ibid.

28 Prak Chan Thul, “Hu wants Cambodia help on China Sea dispute, pledges aid,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 2012.

29 “ASEAN paralyzed over China sea dispute, say analysts,” Bangkok Post, April 4, 2012.

30 Luke Hunt, “ASEAN + China and Bhutan?” The Diplomat, April 10, 2012.

31 Carlyle A. Thayer, “South China Sea fireworks at the Shangri-la Dialogue?” Thayer Consultancy Background Brief, June 1, 2012.

32 “China: intrusion charge groundless,” Philippines Daily Inquirer, Jan. 10, 2012.

33 “China needs a ‘consistent policy on the South China Sea,’ ” BBC News Asia, April 23, 2012.

34 “Obama, Clinton back PHL’s bid for rules-based solution to maritime spats,” gmanetwork.com, June 9, 2012.

35 Pia Lee-Brago, “China insists on bilateral talks on Spratlys row,” The Philippine Star, April 11, 2012.

36 Fidel V. Ramos, “China, US, Philippines — ‘Saving Face’ (Last of Two Parts)”, www.mb.com, May 19, 2012.

37 “Southeast Asia fails to tackle sea spat with China head on,” Reuters, April 4, 2012.

38 “ASEAN concludes drafting Code of Conduct for South China Sea,” english.sina.com, May 25, 2012.

39 Sopheng Cheang, “Southeast Asia nations, China bring rift to summit,” Associated Press, April 3, 2012.

40 Ibid.

41 “China-Philippines intensify war of words over South China Sea,” voanews.com, May 10,2012.

42 “Telltale signs Scarborough will not be Mischief redux,” asianweek.com, May 4, 2012; Wang Xiaoxcia, “The China-Philippine standoff,” eec.com.cn, April 24, 2012.

43 “Philippines call for ASEAN aid in dispute,” upi.com, April 18, 2012.

44 “China-Vietnam spar over South China Sea,” UPI, June 27, 2012; the last time this happened was in 1992 when China awarded Crestone a block adjacent to Vietnam’s continental shelf but much further away from Vietnam’s coast.

45 Teshu Singh, “The curious case of India’s withdrawal from the South China Sea,” Euroaseareviews.com, June 8, 2012.

46 Rakesh Sharma, “ONGC to continue exploration in South China Sea,” wsj.com, July 19, 2012.

47 “Vietnam warns China to halt oil bids in area awarded to Exxon,” Bloomberg.com, June 27, 2012.

48 “China ‘battle-ready,’ ” Manila Bulletin, June 29, 2012.

49 www.atimes.com, July 3, 2012.

50 Jane Perlez, “Asian leaders fail to resolve disputes on South China Sea during ASEAN summit,” The New York Times, July 12, 2012.

51 “No accord in South China Sea row,” UK Press Association, July 13, 2012; “Breakdowns overshadow accomplishments as ASEAN meeting ends,” voanews.com, July 13, 2012.

52 “South China Sea meeting ends in stalemate,” www.csmonitor, July 13, 2012.

53 “RP slams Chinese ‘duplicity, intimidation,’ ” Agence France-Presse, July 13, 2012.

54 www.reuters.com, July 13, 2012.