A Distant Neighbor: Russia’s Search to Find Its Place in East Asia

*Author, Tsuneo Akaha is Professor of International Policy Studies and Director of the Center for East Asian Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies, Monterey, California.

HISTORICALLY, EAST ASIAN countries have tended to see Russia as a “distant neighbor” with a distinct civilization — neither European nor Asian — and political and strategic interests at odds with their own.1 Since the end of the Cold War, however, Russia has undergone sweeping and often tumultuous changes, politically, economically and socially. As a result, its foreign and security relations with the neighboring countries of East Asia have improved substantially. Today, as President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev look to stabilize national politics and modernize the nation’s economic foundations, Moscow is paying greater attention to Russia’s role in regional integration in East Asia;2 one sign of this is that the APEC summit in September 2012 will be held in Vladivostok, the largest city in Russia’s Far East. Moscow is reported to have invested $15 billion or more in the Primorsky region ahead of the summit, an amount 60 times Vladivostok’s annual city budget.3

Does Moscow have a realistic strategy for taking advantage of its Asian neighbors’ economic dynamism by further expanding bilateral political relations and becoming part of the development of multilateral co-operation and integration in East Asia? Does Moscow have a realistic vision and effective strategy for turning its Far Eastern territories, long a front-line fortress against foreign threats, into a “bridge to East Asia?” The Russian government is investing tens of billions of dollars in large-scale infrastructure development in this long-neglected part of the country. Russia’s growing engagement with Asia is also evident in its participation for the first time, along with the United States, in the East Asia Summit (EAS) held in Indonesia in November 2011. Many obstacles remain, however, to Russia’s constructive and effective participation in East Asia’s deepening regional integration.

Geographically, Russia is very much a part of East Asia. In other aspects, however, Russia’s position in this region is not as well defined. Politically, Russia has more or less normal relations with all East Asian countries, both small and large, developed and developing, although the depth, scope and nature of those relations vary widely. Its bilateral trade and economic relations with regional neighbors vary from somewhat significant, as with China and Japan, to virtually negligible, as with most Southeast Asian countries. Russia’s impact on the international relations of the region has long been based largely on its ideological and military interests vis-à-vis the other major contenders for influence in Northeast Asia, i.e. Japan in the first half of the 20th century and the US and China during the second half. However, with the end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union came the end of ideological and military rivalries among the regional powers and a precipitous weakening of Moscow’s political influence in the region. Most importantly, post-Soviet Russia virtually disappeared from the strategic radar of the US, the lone superpower in the world and the dominant political actor in post-Cold War East Asia, forcing Moscow to reach out to Beijing in forging a “strategic partnership” to counter the dominance of the US in the regional political landscape. Moscow’s co-operation with Beijing, both bilaterally and multilaterally, for example, through the Shanghai Co-operation Organization (SCO), has helped Russia maintain its relevance to regional politics. Moscow has also retained a modicum of influence in the region through its participation in the Six-Party talks over nuclear developments in North Korea. Today, however, none of the big powers in the region considers Russia a major security factor either positively or negatively.

One area where Russia is an important and growing factor is the energy sector. The nation has the potential to exploit its energy resources — namely oil and natural gas — not only for its economic development but also as a source of political influence, particularly vis-à-vis the energy-hungry Northeast Asian countries — China, Japan and South Korea. Energy is no longer simply an economic asset but also holds important implications for Russia’s strategic position in the region and beyond. With some of the world’s largest oil and natural gas reserves within its territory, Russia has developed an active energy diplomacy, wooing foreign energy trade partners and foreign investment in the exploration and exploitation of its rich reserves.4 Elsewhere Moscow has attempted to exploit foreign partners’ dependence on its energy supplies in its foreign policy.5 Today, one cannot describe Russia’s role in international relations without reference to energy. One may go so far as to suggest that energy has become one of the essential parts of Russia’s identity in the world.

What are the implications of Russia’s unbalanced presence in East Asia for its role in the region’s future, which will be characterized by deepening market integration and institutionalized multilateralism for facilitating and managing regional integration? This brief analysis will locate Russia in East Asia in terms of the main elements of its relations with the region’s major powers in political, economic, and military-defense spheres and explore its prospects as a constructive partner in regional integration.

Sizing Up Russian Power

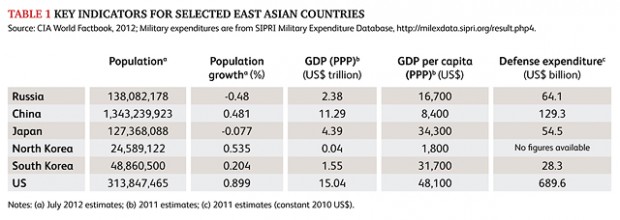

One key indicator of a nation’s relative power is its population size. Russia’s population in 2012, 138 million, was the third largest among East Asian countries, after China (1.34 billion) and the US (314 million), and ahead of Japan (127 million). However, demographic trends in Russia (along with Japan) indicate a declining vitality, with population growth in 2009 estimated at -0.48 percent (-0.07 percent in Japan), compared with estimated growth rates of 0.89 percent in the United States, and 0.48 percent in China (see Table 1).

Russia’s GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms in 2011 stood at $2.38 trillion, far smaller than the United States’ $15.04 trillion, China’s $11.29 trillion and Japan’s $4.39 trillion. Russia’s per capita GDP, at $16,700, compared favorably with China’s $8,400, but lagged far behind the United States’ $48,100, Japan’s $34,300, and South Korea’s $31,700 (see Table 1).

Russia’s weight in East Asia has long been based on its military might and presence in the region, and the nation still remains a formidable military power. Its defense expenditure, estimated at $64 billion, was the third largest in the region after the United States ($689 billion) and China ($129 billion), and exceeded Japan’s $54 billion and South Korea’s $28 billion.6

Relations with East Asian Powers

With its population shrinking, its economic performance wanting, yet its military capacity remaining substantial, Russia’s political performance in East Asia has been very limited. As the processes of regional integration around the world have social, economic, security, and political dimensions, the prospects for Russia’s potential role in regional integration in East Asia are mixed.

Russia’s most important political partner in East Asia is China.7 However, the relationship, defined as a “strategic partnership,” has its limits.8 Moscow and Beijing share a common interest in denying the US a monopoly on the regional political agenda. They have resolved their long-standing border dispute, enjoyed frequent reciprocal visits by their leaders and been united in opposition to US political interests, such as the US-led invasion of Iraq, nuclear developments in Iran, the “Arab Spring” and the impending civil war in Syria. The generally strong political ties between Russia and China are limited, however, by a number of bilateral issues. Bilateral trade has been growing much more slowly than their leaders had hoped. Moscow’s ambiguous position on supplying oil and gas to China via pipelines has frustrated China’s aggressive energy import policy, confounding the Sino-Japanese competition for the energy resources in Siberia and the Russian Far East.9 The presence of Chinese traders, workers and tourists in Russia’s Far Eastern territories has also complicated bilateral policy co-ordination, exposing different interests and priorities between the two countries’ central governments and their regional leaders.10 Although earlier fears of China’s “creeping expansion” or “peaceful invasion” of the Russian Far East have dissipated due to improvement in bilateral migration management between Moscow and Beijing since the mid-1990s, such fears may be easily rekindled as the balance of economic power continues to shift in China’s favor.11 Even the notable progress that Russia and China have made in forging multilateral co-operation through the SCO is unlikely to help the two sides overcome the effects of the mutual suspicion and their changing balance of economic power.12

Russia has expanded bilateral trade and economic relations with Japan to their highest level since the end of the Cold War, but they are far from reaching the full potential indicated by their geographical proximity and the complementarity of their economic assets and needs.13 Although Russia’s political relations with Japan are potentially as important as those with China, the long-standing sovereignty dispute between the two countries over the Southern Kuril Islands/Northern Territories remains a formidable barrier to building a relationship of mutual trust.14 Recent events have elevated the political salience of the territorial dispute. The leadership in Moscow has intensified its appeal to patriotism and used the islands issue to this end. On July 7, 2010, the Russian Duma passed legislation establishing September 2 as the date to commemorate the end of the Great Patriotic War, that date in 1945 being the day when Japan signed the instrument of surrender. On Sept. 28, 2010, then-President Dmitry Medvedev and Chinese President Hu Jintao issued a joint statement commemorating the 65th anniversary of the war and pledged further deepening of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership. This was followed by Medvedev’s visit to Kunashiri Island on Nov. 1, 2010, which Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan called “an unforgivable outrage.” In response, an ultranationalist group in Japan desecrated the Russian national flag at a demonstration near the Russian embassy in Tokyo.

Ironically, Medvedev’s visit to the disputed island is a demonstration of Moscow’s interest in developing the economic infrastructure of the Russian Far East, including the Southern Kurils, for which Russia is courting Japan as an important economic partner. Japan also sees mutual benefits in closer economic ties with Russia to diversify its energy supplies, particularly after the March 2011 nuclear reactor meltdown in Fukushima and the subsequent shutdown of all of the nation’s nuclear reactors pending safety checks. For example, Japan has indicated interest in co-operating with Russia in building a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant in Vladivostok. The project is designed to further diversify sources of LNG supplies to Japan and reduce its current heavy reliance on Asian and Oceanic sources. In the fiscal year 2009, Russia accounted for 6.5 percent of Japan’s LNG imports, but the planned project will boost the level above 10 percent.15 We will turn to this aspect of Russia’s policy in East Asia below.

Following his resumption of the presidency in May 2012, Vladimir Putin expressed readiness to resolve the island dispute if Japan was willing to compromise. With nationalist sentiments mounting on both sides, however, the prospects for a resolution are very dim. In addition, the fragile political leadership in Japan severely constrains Tokyo’s maneuverability on this issue.

Moscow’s relations with Washington are important on their own merit as well as for the influence they exert on its relations with both Beijing and Tokyo. During the early years of the Cold War, Russia and China were ideological allies opposed to the US, but a political rift and border disputes between the socialist giants led to a split in the socialist camp and paved the way for Sino-American rapprochement in the 1970s. The end of the Cold War seemed to remove any ideological sources of division between Moscow, Beijing and Washington, but the United States’ emergence as the sole superpower after the demise of the Soviet Union brought the former socialist allies closer. The resolution of Sino-Russian border disputes in the 1990s also brought Russia and China closer.16 Similarly, Russia’s ideological conflict with the US defined its political relations with Japan during the Cold War, but the end of the superpower conflict slowly led to warmer Russo-Japanese relations. This seemed to raise hopes for a territorial resolution between Russia and Japan but, ironically, it also elevated the political salience of the island dispute in Japan. The Korean crisis, namely North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile development program, has also brought Moscow, Beijing and Tokyo into closer co-operation, although their differences remain. Until North Korea’s repeated nuclear weapons tests and missile launches in 2009, Moscow and Beijing rejected Washington and Tokyo’s call for sanctions against Pyongyang. Following North Korea’s threatening behavior — and its declaration that it would not return to the Six-Party talks, however, Russia and China have come to accept the need to use sanctions to induce a more conciliatory policy from Pyongyang. All said, however, Moscow’s influence in the Six-Party talks is very limited, especially in comparison with that of China and the US.17 Russia’s opposition to US hard-line policies toward North Korea, as well as toward Iran and Syria, is likely to continue under Putin’s leadership.

Russia’s engagement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is fairly recent and its influence at present is marginal.18 In 1996, Russia became an ASEAN dialogue partner, and on Nov. 29, 2004, it acceded to the Treaty of Amity and Co-operation in Southeast Asia of 1976 (the Bali Treaty). In November 2011, Russia, along with the US, joined the East Asia Summit for the first time, indicating the growing acceptance of Russia by ASEAN countries. Russia also participated for the first time in the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting in October 2010, along with the 10 ASEAN members, China, the US, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand. Russia wanted to join the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) since the multilateral dialogue forum was created in 1996.19 Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s participation in ASEM in Brussels in October 2010 marked Russia’s first appearance. The question of whether Russia should be considered a European or an Asian country stood in the way of its participation in ASEM. Having failed to join as a European country (because Russia is not a member of the European Union), Russia was able to join ASEM as a “Eurasian country.”20

Russia’s Place in East Asia’s Economy

How important is Russia as a trade partner in East Asia? In 2005, Russia’s trade with the other countries of the region amounted to barely 2 percent of the entire trade within Northeast Asia. In contrast, China (excluding Hong Kong) represented 33 percent, Japan 26 percent and the US and South Korea each 12 percent, of the total intra-regional trade.21 This picture does not change even if we look at exports and imports separately — Russia’s exports and imports to other Northeast Asian countries, including the US, amounted to only 2 percent of the region’s total.22

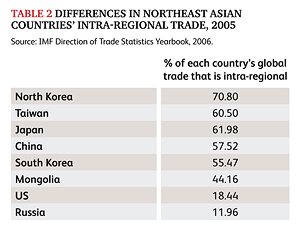

In 2005, Russia’s trade with its Northeast Asian neighbors, including the US, constituted around 12 percent of its worldwide trade. Clearly, Russia finds most of its trade partners elsewhere in the world. By contrast, China’s trade within the region represented around 60 percent of its global trade, for Japan the figure was about 62 percent and for South Korea more than 55 percent (see Table 2).

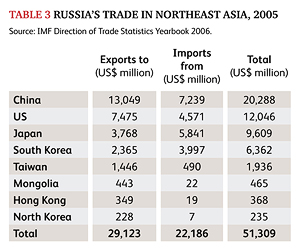

23 Trade in Northeast Asia is significantly more important to other regional countries than it is to Russia, and Russia is the least important trade partner to the other countries of Northeast Asia. As Table 3 shows, Russia’s most important trade partner in Northeast Asia in 2005 was China, with 44 percent of Russian exports in the region going to China and 33 percent of its imports in the region coming from China. The second most important trade partner of Russia was the United States (26 percent of Russia’s exports and 21 percent of imports),

followed by Japan (13 percent and 26 percent). 24 In short, Russia is the least integrated East Asian economy vis-à-vis the other economies of the region. Even among the Northeast Asian countries, Russia is a small, if not insignificant, trade partner.

However, Russia’s potential role in regional trade is substantial, particularly in the energy sector. As noted at the outset, Russia holds huge reserves of oil and natural gas. In 2006, it possessed the eighth largest proven oil reserves in the world. Russia, with 60 billion barrels, followed Saudi Arabia (264.3 billion), Canada (178.8 billion), Iran (132.5 billion), Iraq (115 billion), Kuwait (101.5 billion), the United Arab Emirates (97.8 billion) and Venezuela (79.7 billion). Russia’s proven natural gas reserves (1,680 trillion cubic feet) were the largest in the world, ahead of Iran (971 trillion), Qatar (911 trillion), Saudi Arabia (241 trillion), United Arab Emirates (214 trillion),

the US (193 trillion), Nigeria (185 trillion), Algeria (161 trillion) and Venezuela (151 trillion).25 If successfully developed, these resources can boost Russia’s economic profile to unprecedented levels.

This has several implications. First, to the extent that Moscow relies on its ability to develop and export its energy resources for pursuing some of its foreign policy goals, global energy prices will have a major impact on Russia’s ability to leverage those resources. Second, the development of the resources in question requires substantial investment in infrastructure, including pipelines and other transportation facilities as well as refineries and petrochemical production facilities. This in turn calls for investment from foreign partners. Third, the nation’s energy reserves may also be exploited to fuel political rivalries between their potential importers, such as China and Japan. Indeed, there has already been much written on this aspect of Russia’s international behavior. 26 Fourth, while Russia enjoys unprecedented energy export revenues, the nation also needs to diversify its economy, gradually reducing its dependence on that very lucrative sector. Does Moscow have the wisdom and the political will to allocate a growing portion of its revenue to the development of the non-energy sector? In contrast to the modern and post-modern economic structures of its East Asian neighbors, will Russia remain largely an exporter of primary commodities and an importer of high-value-added products? Former President Medvedev answered this question in the negative when he stated in his speech “Go, Russia” in September 2009:

The global economic crisis has shown that our affairs are far from being in the best state. Twenty years of tumultuous change has not spared our country from its humiliating dependence on raw materials. Our current economy still reflects the major flaw of the Soviet system: it largely ignores individual needs. With a few exceptions domestic business does not invent nor create the necessary things and technology that people need. We sell things that we have not produced, raw materials or imported goods. Finished products produced in Russia are largely plagued by their extremely low competitiveness.27 (Emphases added.)

Medvedev went on to point out that contemporary Russia is plagued by three “social ills” and that the nation needs to overcome them if it is to regain its great power status in the increasingly competitive world. As he put it, one of the social ills was “centuries of economic backwardness and the habit of relying on the export of raw materials, actually exchanging them for finished products.”28 (Emphasis added.)

We will return to this question when we discuss the role of the Russian Far East in the nation’s relations with the neighboring Asian countries.

How Russia Sees China, Japan & the United states

Russia has been geographically close but culturally and historically distant from East Asian societies, and most Russians are oriented more toward Europe. The post-Soviet search for national identity among the Russian elite says much about their ambivalence toward the international community, including East Asia.

This does not necessarily mean that there is no possibility of Russians developing social and cultural ties with other peoples of the region. The presence of Asians in Russia, including in its Far Eastern territories, as well as the growing number of Russians resident in neighboring Asian countries will no doubt contribute to the growth of transnational networks of individual and professional linkages involving Russian nationals. For the networks to become a significant

integrating force in East Asia, however, tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of Russians need to join those networks, but this is not a likely prospect in the foreseeable future. . On the contrary, the population in the Russian Far East has dropped from a peak of around 8 million in the late 1980s to about 6.5 million today, a consequence of internal migration from the region to European Russia in the post-Soviet years of economic stagnation and social instability in the Russian Far East.

How do Russians themselves view their own country and its relations with the neighboring countries of Asia? Some recent public opinion polls in Russia offer interesting answers.

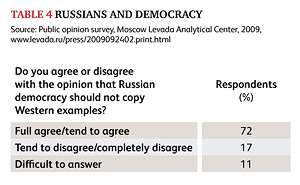

According to a 2009 public opinion survey by the Levada Analytical Center,29 Russians tend to view their own political evolution as unique and not readily comparable with the experience in the West

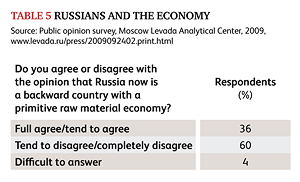

(see Table 4). Nor do they have any illusions about the state of their economy, with one-third of the respondents thinking their country is backward with a primitive raw material-based economy (see Table 5), echoing former President Medvedev’s concern noted earlier.

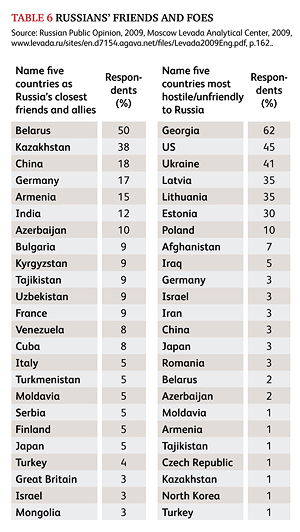

In another public opinion survey conducted by the Levada Analytical Center in 2009, 32 percent of respondents believed Russia should co-operate with China in implementing its foreign policy, compared with 22 percent and 15 percent choosing Japan and the US, respectively, in the same context.30 Meanwhile, 18 percent of respondents considered China

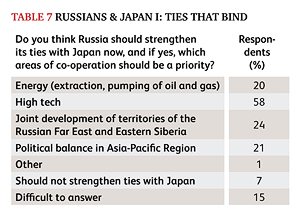

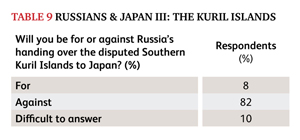

one of the five closest friends and allies of Russia, after Belarus at 50 percent and Kazakhstan at 38 percent (see Table 6). In comparison, only 5 percent considered Japan in the same light. The US did not even appear among the top 20 countries on the list of closest friends and allies; on the contrary, 45 percent of the respondents named the US among the five most hostile and unfriendly countries toward Russia, second only to Georgia (62 percent). Only 3 percent put Japan and China on the list of most hostile and unfriendly countries. Even fewer respondents (1 percent) considered North Korea in a negative light. An overwhelming majority (78 percent) of the respondents showed favorable attitudes toward Japan (see Table 7).31 Russians’ interest in co-operation with Japan relates overwhelmingly to technological and economic aspects, although there is also interest in bilateral co-operation in the energy sector and development of Eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East, as well as in the role of bilateral co-operation in maintaining political balance in Asia-Pacific. While a majority (55 percent) of respondents in the Levada survey saw the need to conclude a peace treaty with Japan (see Table 8), an overwhelming majority of 82 percent was opposed to territorial concessions to Japan (see Table 9).

The Role of the Russian Far East

If Russia is to expand its economic ties with East Asian countries, its Far Eastern territories will be an essential link.32 In this context, the Russia Far East represents both an opportunity and a burden for Moscow. It presents an opportunity because it is geographically adjacent to the dynamic East Asian economies and can and does serve as an entry point for capital, technology, services and labor from the neighboring countries. During the Soviet period,

however, Moscow failed to develop the necessary infrastructure in the Far East to take advantage of these complementarities. Although post-Soviet Russia appears interested in engaging China, Japan, South Korea and the US in economic co-operation based on market principles, its unpredictable behavior in international transactions, such as in the offshore oil and gas development in Sakhalin, has frustrated international business partners. The numerous pipeline projects in Eastern Siberia and the Far East have also suffered from a lack of consistency and

stability in Moscow’s economic strategy in relation to potential partners in development projects in those territories.33

There are real and potential opportunities as well as liabilities that Russia’s Far East represents for Moscow.34 The most obvious advantage the region enjoys is its abundant natural resources, which puts it in a complementary position vis-à-vis the resource-hungry economies of East Asia. Second, the region’s geographical proximity to East Asia offers Russian exporters an advantage over exporters in distant

locations. The export of value-added products in Russia stands a good chance of improving the nation’s balance of trade relative to the East Asian economies if the exports are of high quality and price-competitive. Third, the Russian Far East needs large investment capital for its industrial modernization and infrastructure development, and Asia’s high savings and capital accumulation might be exploited if the investment climate in the Far Eastern region were substantially improved. Fourth, as with investment capital, the vast array of quality technologies available in East Asia can offer substantial assistance with the industrial modernization of the Russian Far East. Fifth, the Russian Far East stands to benefit from a well-managed import of cheap Chinese labor, particularly in those sectors where labor shortages are almost chronic including agriculture, construction and services.

Arguably the largest disadvantage that the Russian Far East has is its small and declining population, which saps the vitality of the region’s economy in terms of economic output and the consumer market. After peaking at around 8 million in the late 1980s, the region’s population slid to less than 7 million in 2010, with further declines expected going forward.35 Second, the abundance of natural resources in the region is also a source of weakness to the extent that Moscow defines the Far East’s role almost exclusively as a source of raw materials for domestic use or for export. That limits infrastructure development to projects that relate directly to the exploration and development of those resources to the neglect of modern industrial and social needs. A related problem is the harm the development of natural resources has done and continues to do to the region’s natural environment and the health of the local populations.36 Fourth, the transportation, communication and other basic infrastructure of the region needs substantial improvement if it is to support the level of economic activity and population growth required to sustain a viable future in the context of the growing economic competition in East Asia. However, there is very little indigenous investment capital in the region, a fifth major disadvantage the Russian Far East suffers. This means the region must continue to depend on “subsidies” from Moscow and investment from foreign sources. Sixth, the distance from Russia’s center — Moscow — has been an obvious disadvantage for the Russian Far East in that the sheer geographical distance has kept transportation costs quite high. Foreign investment in infrastructure development in the region would lighten the burden on Moscow but large-scale investment is not likely unless and until Moscow shows an unequivocal commitment to the economic development and modernization of the region and Russia proves itself to be a reliable supplier of raw materials exports to foreign partners. Seventh, and finally, the interests and priorities of the center and the periphery are often at odds with each other. For example, the strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing has not been translated into a stable relationship between the Russian Far East and China’s northeastern provinces. The visible gap in infrastructure development between the Chinese and Russian sides of the Far Eastern border has been a sour spot in cross-border relations, and many residents of the Far Eastern communities continue to harbor anti-immigrant sentiments even though border management has improved substantially since the mid-1990s.37

Does Moscow have the political will and commitment to invest the necessary financial resources to promote the advantages and reduce the disadvantages of its Far East? What is required is a major reorientation of Russia’s priorities toward its territories there. Will Moscow translate its recent public pronouncements about major investment in modern infrastructure ahead of the 2012 APEC summit into a sustained development program long after the photo opportunities at the meeting are over? It is reported that the event might attract $100 billion in investment to the Russian Far East and that spending on summit-related activities has already boosted the region’s economy.38 The question remains, however, whether Moscow will sustain such investment far beyond the summit or whether the investment is simply a shot in the arm with only short-term and limited benefit to the region.39 Skeptics who have watched Moscow’s numerous past plans for the region’s development and modernization evaporate may well be justified in their continuing doubts. On the other hand, will the neighboring countries, namely China, Japan and South Korea, commit public funds into the infrastructure development required even to realize the existing pipeline projects in Eastern Siberia and the Far East? For this to happen, Moscow must be fully committed to develop and deliver the promised oil and natural gas supplies to its East Asian neighbors. Unfortunately, there are as many international skeptics as there are domestic doubters in this regard.

Russia and Regional Integration in East Asia

Russia has been expanding its participation in multilateral frameworks for international co-operation in East Asia since the 1990s. In Northeast Asia, Russia has been a participant in the Six-Party talks over the problem of North Korea’s nuclear program. However, Moscow’s influence in the multilateral talks is limited, particularly in comparison with that of the other parties to the forum. It has exercised its influence through co-ordination with Beijing on the way to deal with North Korea’s nuclear and missile development and military provocations, consistently arguing against sanctions against Pyongyang. Although Russia assumed the chairmanship of the task force under the Six-Party framework to discuss multilateral security architecture beyond the Six-Party talks, North Korea quit the multilateral talks in 2009 and no progress has been made on the establishment of a longer-term security framework.40

Russia’s engagement with multilateral institutions in Southeast Asia has lagged behind other major regional powers like China and Japan.41 This is largely due to Russia’s limited economic ties with Southeast Asia and also because of Moscow’s loss of sustained interest in the region in the aftermath of the Cold War. During the Cold War, Russia viewed Southeast Asia as a theater of ideological rivalry with Beijing and was deeply engaged in the region, particularly through its support of Vietnam. The end of the Cold War and the Sino-Russian rapprochement ended Russia’s active engagement in this part of Asia. It took nearly a decade before Moscow began to undertake diplomatic efforts to regain its influence in Southeast Asia. Russia joined the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in 1994. In 1996, Russia became an ASEAN dialogue partner and in 2004 Moscow signed the Treaty on Amity and Co-operation. Moscow recognized the growing importance of Southeast Asia and made serious efforts to develop diplomatic and economic ties with ASEAN countries, particularly Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia, and has been holding annual summit meetings with ASEAN since 2005. Furthermore, on Oct. 11-13, 2010, Russia joined the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ meeting for the first time, along with China, the US, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand. Also in October 2010 Russia, together with Australia and New Zealand, took part in the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), a multilateral forum designed to deepen the relationship between Asia and Europe through dialogue on political, security, economic, and educational-cultural issues. Most recently, in November 2011, Russia and the US joined the EAS for the first time.

Finally, 14 regional governments in the Russian Far East are members of the little known Association of Northeast Asia Regional Governments, which was formally established in 1996. The association includes the Republic of Buryatia, Republic of Sakha, Primorsky Territory, Khabarovsk Territory, Amur Region, Irkutsk Region, Kamchatka Region, Sakhalin Region, Zabaikalsky Territory, Krasnoyarsk, Tomsk Region, Republic of Tyva, Altai Territory, Magadan Region and their counterparts in China, Japan, North Korea, South Korea and Mongolia. The association members meet every other year to discuss regional-level co-operation. It has subcommittees on economy and trade, the environment, cross-border issues, tourism, mineral resources development, women and children, education and cultural exchange, disaster prevention, science and technology, oceans and fisheries, and energy and climate change issues.42

What are the implications of the above developments for Russia’s place in regional integration in East Asia? Integration may proceed along economic, political,

security and social-cultural dimensions, but in this region integration has progressed primarily in the economic sphere. Russia’s economic links to the region are underdeveloped and the nation’s impact on the rest of the regional economies is limited. Thus, Russia remains a marginal factor in regional integration in East Asia.

How about APEC and Russia’s role in it? Since Russia joined in 1998, the multilateral dialogue forum has played a diminished role in regional and global trade liberalization against the unmistakable trends toward bilateral and minilateral free trade agreements (FTAs). Furthermore, the major trading powers in the region do not see Russia as a particularly attractive partner for bilateral FTAs or economic partnership agreements (EPAs). Can Russia change these trends? Given its limited economic ties to the region, prospects are rather limited. More than anything Russia can do, regional and global trends are likely to be set by the commitment (or lack of commitment) on the part of the world’s major trading powers including China, Japan, the US and the EU, to re-invigorate the World Trade Organization as the institution for global trade liberalization.

The upcoming APEC Summit in Vladivostok will be significant not so much for what Russia will contribute to the dialogue as what its hosting of the regional summit will do for the economy of the Russian Far East. Indeed, this is what Russia wants to achieve. As APEC Chair in 2012, Russia hopes to “promote the domestic economy organic integration [sic] into the system of economic ties in the Asia-Pacific Region (APR) in the interests of modernization- and innovation-driven economic development, primarily in Siberia and the Russian Far East.”43

In East Asia, regional political integration remains a long-term possibility at best, and an uncertain prospect at worst. Historical legacies, multiple sovereignty disputes and major-power rivalries are likely to drive Russia and other main actors to continue to favor the unilateral and bilateral approaches they have pursued in dealing with sensitive political issues. The regional powers are not likely to surrender their sovereignty to an EU-like supranational authority in the foreseeable future. There are also serious doubts about the prospect of the Six-Party talks resolving the North Korean nuclear crisis. Even though Moscow has been advocating a peaceful resolution to the crisis and development of a permanent regional security architecture in post-crisis Northeast Asia, its influence in realizing these goals is very limited. The future of the North Korean nuclear crisis will depend, first and foremost, on US policy — whether Washington will be willing to commit itself unequivocally to a non-military resolution of the problem and also recognize the current regime in Pyongyang in return for the denuclearization of North Korea — and whether Pyongyang will accept these terms and fully implement its non-nuclear pledge in a verifiable manner. The post-crisis security environment in Northeast Asia will depend on the strategic interests and priorities of the US and China, more than on Russian interests or capabilities.

Given Russia’s essential cultural distance from most East Asian societies and the perennial search for national identity among the Russian elite, the ambivalence toward becoming a full-fledged member of an East Asian Community and sharing a common identity with its Asian neighbors is hardly a surprise.

In the economic sphere, energy offers Russia the most promising avenue toward closer economic relations with its regional neighbors, but it remains to be seen how the strategic value of energy resources, which Russia will surely want to exploit, can be integrated functionally with the market forces that have driven and continue to drive integration in East Asia. Because of its strategic importance to Russia’s economic future, energy will be used as Moscow’s instrument of diplomacy, adding to the realist characteristic of Russia’s engagement with other regional powers, which will also see energy security as a core national interest. Moreover, there is no framework for integrating the energy policies of the region. Instead, the major energy importing countries — China, Japan and South Korea — are operating in the global energy market, although the political instability in the Middle East does present opportunities for Russia as a supplier of oil and natural gas to these economic powers.

In conclusion, if Russia is to develop its ties with its Asian neighbors more deeply, it needs to engage more actively in the growing multilateralism, demonstrate a firm commitment to the development of the Russian Far East as a “bridge to East Asia,” and undertake major modernization efforts in the domestic economy. Then and only then will Russia be able to take full advantage of the mounting integrative forces in East Asia and also contribute to the further development of market-driven regional integration aided by regional institutional mechanisms. A further emphasis on the development of its already formidable military power, unless accompanied by stepped-up investment in the civilian sector of its economy, will keep Russia as a “distant neighbor” in East Asia, not only in terms of civilization but also politically and economically.

Tsuneo Akaha is Professor of International Policy Studies and Director of the Center for East Asian Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies, Monterey, California.

NOTES

1 The view of Russia as a “distant neighbor” is particularly acute among the Japanese. See Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Jonathan Haslam and Andrew C. Kuchins, eds., Russia and Japan: An Unresolved Dilemma between Distant Neighbors (Berkeley: University of California, 1993).

2 Hiroshi Kimura and Shigeki Hakamada, eds., Ajia ni sekkinsuru Roshia (Russia Moving Closer to Asia), (Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido Daigaku Shuppankai, 2007).

3 Sebastian Strangio, “As Asia Rises and Europe Declines, Russia Invests Its Hopes in Its Far East,” The Atlantic, Oct. 27, 2011, www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/10/as-asia– rises-and-europe-declines-russia-invests-its-hopes-in-its-far-east/247353/ (accessed May 20, 2012).

4 www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0872964.html (accessed May 15, 2009).

5 For Western analyses of Russia’s energy diplomacy, see A. Jaffe and R. Manning, ”Russia, Energy, and the West,” Survival, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2001), pp. 133-152; Edward L. Morse and James Richard, “The Battle for Energy Dominance,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 81, No. 2 (March-April 2002), pp. 16-31; Lyle Goldstein and Vitaly Kozyrev, “China, Japan, and the Scramble for Siberia,” Survival, Vol. 48, No. 1 (2006), pp. 163-178. See also Shoichi Itoh, “Russia’s Energy Diplomacy toward the Asia-Pacific: Is Moscow’s Ambition Dashed?” in Energy and Environment in Slavic Eurasia: Toward the Establishment of the Network of Environmental Studies in the Pan-Okhotsk Region (Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University, 2008) pp. 33-65; Shoichi Itoh, “Chu-Ro enerugi kyoryoku kankei” (Sino-Russian Energy Co-operation), in Hiroshi Kimura and Shigeki Hakamada, eds., Ajia ni sekkinsuru Roshia (Russia Moving Closer to Asia) (Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido Daigaku Shuppankai, 2007) pp. 98-117; Tadashi Sugimoto, “Roshia no enerugi shigen to gaiko” (Russia’s Energy Resources and Diplomacy), in Shinji Yokote, ed., Higashi Ajia no Roshia (Russia in East Asia) (Tokyo: Keio Gijuku Daigaku Shuppankai, 2004) pp. 225-253; Hongchan Chun, “Russia’s Energy Diplomacy toward Europe and Northeast Asia: A Comparative Study,” Asia Europe Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2 (2009), pp. 327-343.

6 SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, http://milexdata.sipri.org/result.php4 (accessed June 18, 2012).

7 For balanced analyses of Russia’s relations with China, see “Russia-China Relations Lose Momentum,” Oxford Analytica, April 23, 2009, www.oxan.com/display.aspx?ItemID=DB150651 (accessed November 6, 2009); Richard Weitz, China-Russia Security Relations: Strategic Parallelism without Partnership or Passion? (Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2008); Natasha Kuhrt, Russia’s Policy towards China and Japan: The El’tsin and Putin Periods (London: Routledge, 2007); Akihiro Iwashita, “9.11 jiken igo no Chu-Ro kankei” (Sino-Russian Relations since the 9/11 Incidents), in Hiroaki Matsui, ed., 9.11 jiken igo no Roshia gaiko no shin tenkai (Post-9/11 Evolution of Russian Diplomacy) (Tokyo: Nihon Kokusaimondai Kenkyujo, 2003), pp. 207-230.

8 Weitz, op. cit.

9 Itoh, “Russia’s Energy Diplomacy…” See also Peter Rutland, “Roshia no Ajia ni okeru yakuwari” (Russia’s Role in Asia), in Kimura and Hakamada, eds., Ajia ni sekkinsuru Roshia, pp. 31-48.

10 Elizabeth Wishnick, “Migration and Economic Security: Chinese Labor Migration in the Russian Far East,” in Tsuneo Akaha and Anna Vassilieva, eds., Crossing National Borders: Human Migration Issues in Northeast Asia (Tokyo: UNU Press, 2005), pp. 68-92.

11 See Kim Iskyan, “Selling off Siberia: Why China Should Purchase the Russian Far East,” posted July 28, 2003, www.slate.com/id/2086157/ (accessed November 13, 2009).

12 Bobo Lo, “A Partnership of Convenience,” New York Times, June 7, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/06/08/opinion/ a-partnership-of-convenience.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all (accessed June 8, 2012).

13 Valeri O. Kistanov, “Higashi Ajia shokoku to Roshia no keizai kankei” (Economic Relations between East Asian Countries and Russia), in Yokote, ed., Higashi Ajia no Roshia, pp. 203-224, particularly pp. 209-214.

14 For recent analyses of the Russo-Japanese territorial dispute, see Akihiro Iwashita, Hoppo ryodo: 4 demo 0 demo, 2 demo naku (The Northern Territories Problem: Neither 4 Nor 0, or 2), Tokyo: Chuko Shinsho, 2005; Akihiro Iwashita, Kokkyo: Dare ga kono sen wo hiitanoka (National Borders: Who Drew Them?) (Sapporo: Hokkaido Daigaku Shuppankai, 2006); Hiroshi Kimura, “Hoppo ryodo henkan ni ojinu Roshia” (Russia Refusing to Return the Northern Territories), in Kimura, Gendai roshia kokkaron: Puchin gata gaiko towa nanika (The Contemporary Russian State: What Is a Putinesque Diplomacy?) (Tokyo: Chuokoron Shinsha, 2009), pp. 263-293. For earlier analyses, see Hiroshi Kimura, Japanese-Russian Relations under Gorbachev and Yeltsin (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2000); Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, The Northern Territories Dispute and Russo-Japanese Relations, 2 volumes (Berkeley: University of California, 1998); James E. Goodby, Vladimir I. Ivanov and Nobuo Shimotomai, eds., ‘Northern Territories’ and Beyond: Russian, Japanese, and American Perspectives (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1995); Vladimir I. Ivanov and Karla S. Smith, eds., Japan and Russia in Northeast Asia: Partners in the 21st Century (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1999.

15 Yomiuri Online, December 14, 2010, www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/business/T101213003043.htm (accessed December 15, 2010).

16 Iwashita, op. cit..

17 For a similar assessment, see Hiroshi Kimura, “Roshia no Chosen hanto seisaku” (Russia’s Policy in the Korean Peninsula), in Kimura and Hakamada, eds., Ajia ni sekkinsuru Roshia, pp. 212-244.

18 For a discussion of Russia’s relations with ASEAN, see Kato Mihoko, “Russia’s Multilateral Diplomacy in the Process of Asia-Pacific Regional Integration: The Significance of ASEAN for Russia,” in Iwashita Akihiro, ed., Eager Eyes Fixed on Eurasia: Russia and Its Eastern Edge, 21st Century COE Program Slavic Eurasian Studies, No. 16-2 (Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University, 2007).

19 “Speech by Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Igor Ivanov at the Session of the Russia-ASEAN Postministerial Conference, Phnon Penh, June 19, 2003,” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Russian Federation, no. 1441-19-06-2003 June 19, 2003, www.mid.ru/brp_4.nsf/e78a48070f128a7b43256999005bcbb3/273f45b5e07cbd4943256d4c0027aac7?

20 http://en.rian.ru/analysis/20101007/160866120.html.

21 Hong Kong’s intra-regional trade represented 15 percent of the region’s total trade in 2005.

22 These statistics are calculated from data in International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook 2006.

23 International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook 2006.

24 These statistics are calculated from data in International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook 2006.

25 www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0872964.html (accessed May 10, 2009).

26 See, for example, Goldstein and Kozyrev; Shoichi Itoh, “Russia’s Energy Policy Towards Asia: Opportunities and Uncertainties,” in Christopher Len and Alvin Chew, eds., Energy and Security Co-operation in Asia: Challenges and Prospects (Stockholm: Institute for Security and Development Policy), 2009, pp.143-165.

27 Dmitry Medvedev, “Go, Russia,” President of Russia website, http://eng.kremlin.ru/speeches/ 2009/09/10/1534_type 104017_221527.shtml (accessed Nov. 13, 2009).

28 Ibid.

29 The Levada Center English website is at www.levada.ru/eng/.

30 Russian Public Opinion, 2009, Moscow Levada Analytical Center, 2009, p. 160, www.levada.ru/sites/en.d7154.agava.net/files/Levada2009Eng.pdf.

31 Ibid., p. 167.

32 For an earlier exploration of this topic, see Tsuneo Akaha, ed., Politics and Economics in the Russian Far East: Changing Ties with Asia-Pacific, London: Routledge, 1997.

33 See, for example, Itoh, “Russia’s Energy Diplomacy…”

34 For a fuller study of the Russian Far East’s advantages and disadvantages, see Tsuneo Akaha, “The Russian Far East as a Factor in Northeast Asia,” Peace Forum (Kyung Hee University, Korea), No. 25 (Winter 1997/98), pp. 91-108; Pavel Minakir, Kunio Okada, and Tsuneo Akaha, “Economic Challenge in the Russian Far East,” in Akaha, ed., Politics and Economics in the Russian Far East: Changing Ties with Asia-Pacific (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 49-69.

35 Vladivostok News, Issue No. 560, Special Reports, March 15, 2007, http://vn.vladnews.ru/issue560/Special_reports/Russias_Far_East_population_continues_to_dwindle (accessed Nov. 6, 2009).

36 For a comprehensive survey of the natural resource base of the region and its environmental and developmental implications, see Josh Newell, The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development, 2nd ed. (McKinleyville, California, Daniel & Daniel, 2004).

37 See Victor Larin, “Chinese in the Russian Far East,” and Wishnick, “Migration and Economic Security,” in Akaha and Vassilieva, eds., Crossing National Borders, pp. 47-67 and pp. 68-92, respectively.

38 “Russia’s Far East Seizes the Moment Ahead of APEC,” Russia Today, http://russiatoday.com/Business/2009-10-12/russias-far-east-apec.html (accessed Nov. 6, 2009).

39 Author interviews with several academic researchers in Vladivostok, September 2011, revealed their views are mixed and tempered. While some individuals are enthusiastic about the ongoing infrastructure development and expect that Moscow’s investment in physical infrastructure, such as airport, roads, bridges, and harbor facilities in and around Vladivostok, will have both short- and longer-term benefits for the region’s economic development and expanded ties with economic partners in the neighboring countries, more individuals are skeptical about the longer-term impact, with some even expressing concern about the skewed distribution of benefits as well as the environmental impact of the large-scale constructions projects in the area.

40 For a recent analysis on Russia’s role and interests, see Stephen Blank, “Russia and the Six-Party Process,” in Tomorrow’s Northeast Asia, Joint US-Korea Academic Studies, Vol. 21 (Washington, D.C.: Korea Economic Institute, 2011), pp. 207-226.

41 For a succinct analysis of Russia’s presence in Southeast Asia since the end of the Cold War, see Leszek Buszynski, “Roshia to Tonan Ajia” (Russia and Southeast Asia), in Kimura and Hakamada, eds., Ajia ni sekkinsuru Roshia, pp. 245-268.

42 The association’s website is at www.neargov.org/app/ index.jsp?lang=en.

43 “APEC-2012 Priorities,” www.apec2012.ru/docs/about/ priorities.html (accessed June 10, 2012). <Global Asia/ Tsuneo Akaha>