Korea pursues ‘hallyu’ initiatives

30 language institutes will be set up around world every year

As part of efforts to boost the staying power of “hallyu” or the Korean wave, the government plans to set up language institutes around the world — 30 or more every year.

Plus, the current Romanization system, already 10 years in existence, will be fixed in order to enable foreigners to read Korean words closer to their original pronunciation.

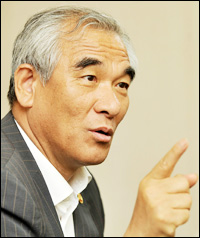

During a recent interview with The Korea Times, Culture, Sports and Tourism Minister Choe Kwang-shik said, “I find that people who have watched Korean TV dramas tend to become enthusiastic in learning our language as well. In this regard, we will build more sejonghakdang, or Korean-learning institutes, in the coming years.”

Sejong was the fourth king of the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910) credited with the creation of the Korean alphabet. The sejonghakdang program was first started in 2007 with 12 facilities in major cities such as Tokyo and New York.

These language classes take place at overseas Korean cultural centers or in universities that have departments for Korean studies.

“There are currently 77 sejonghakdang in 36 countries, but the number is expected to increase to 90 by the end of this year. We hope to add at least 30 every year and develop standard textbooks to be used in these institutions,” the minister added.

The ministry will also select 20 certified teachers to dispatch to the institutes.

“With the establishment of the Sejonghakdang Foundation, we expect to enhance their operation and level of training.”

The culture ministry has extensive responsibilities, encompassing various fields including tourism, sports, broadcasting and the cultural content industry, among others.

Almost 40 organizations are affiliated with the ministry, including the National Institute of the Korean Language (NIKL).

The NIKL is responsible for the controversial Revised Romanization of Korean, which has been the official system in South Korea replacing the older McCune-Reischauer style.

Despite governmental promotion, some foreign residents and scholars have consistently raised criticism over the new system, saying that it has causes confusion and that it does not match actual Korean pronunciation of cities and objects.

The minister was against going back to the old system to assuage opposition from some users of Romanized Korean.

“The new system has been practiced for almost 10 years now. If we were to return to the old system this would cause more confusion,” Choe said. “The best way to deal with this issue is to minimize the flaws and implement measures for improvement.”

“This is not just a matter of switching the Romanization system. Going back and forth on such major policies could hurt how Korea’s global status,” Choe added.

The minister showed apprehension about the immense costs involved in switching Romanization systems.

“When we installed the new system, I heard that more than $260 million was spent changing road signs. If we were to do this once more, we would have to do this all over again.”

Flawed signs at major tourist sites, such as Buddhist temples, have also been a chronic problem.

The nation’s Buddhist temples are major tourist attractions for foreigners, who often rely on English versions of Korean signs to learn about the temples they are visiting. But many are inadequate, containing grammatical and factual errors

The need to enhance the accuracy of these translated signs is becoming more apparent as the templestay program heads into its 10th year.

“We believe that it is of great importance to install accurate English signs at Buddhist temples. We will work with local governments to monitor tourist signs and correct misinterpretations.” <Korea Times/Do Je-hae>