A train crosses the rivers Indus, Nile and Volga

By Rahul Aijaz

KARACHI: A train leaves the station near the Indus River in Sindh province in Pakistan, goes through the Nile River in Egypt and finally arrives at the Volga in Kazan, Tatarstan in Russia. That’s the long journey we undertook starting in early 2020 to late 2021. It’s also the journey we never imagine we would take.

In October 2019, I got the opportunity to participate in Goethe-Institute Pakistan’s Film Talents fellowship. I was among the 15 filmmakers selected from Pakistan and Afghanistan to make films under the framework of the program.

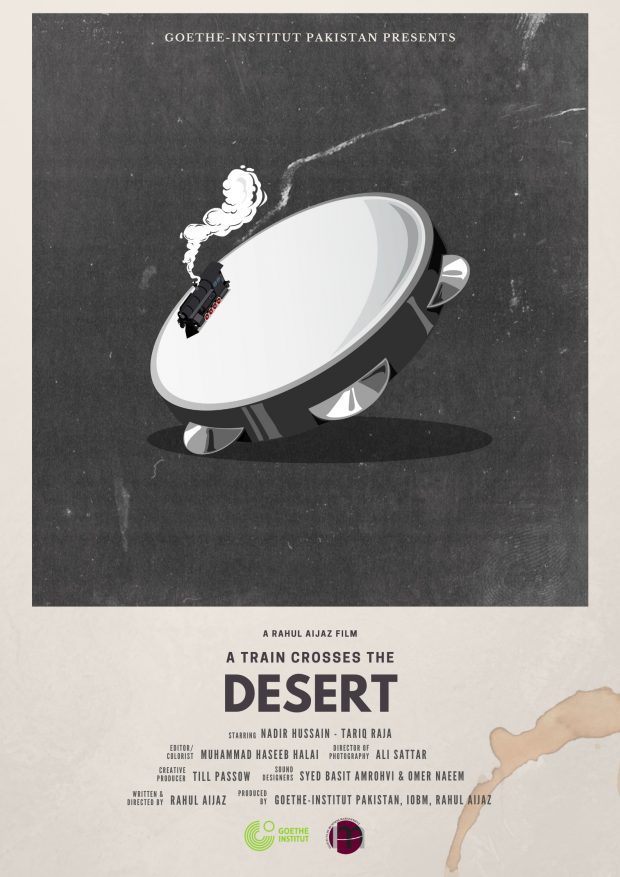

This marked my return to filmmaking after several years of practicing journalism and film criticism across Pakistan and Korea. The train, in fact, was waiting to leave the station and it only left in February 2020 with the start of the production of our short film which was to be titled ‘A Train Crosses the Desert’. It starred Tariq Raja and Nadir Hussain in the lead, with an appearance by Arshad Shaikh.

The story of the film revolved around two brothers, one of which is terminally ill and requests the other to euthanize him. It was inspired by my late cousin Farooq’s death due to cancer in 2018. Further, the ideas of death and suicide have always stayed with me throughout my life. The premise, although, had started from a joke Farooq and I used to have between us. Being massive Game of Thrones fans, we had made a pact, jokingly of course, that we would off ourselves as soon as we watch the episode of the final Game of Thrones season.

Unfortunately, Farooq passed a year before that and I was left with survivor’s guilt and the bittersweet memories while watching the disappointing final season of the once-great show. So, the premise revolving around euthanasia was, for me, the most appropriate way to not only pay an homage to our friendship but also explore the agony one suffers when stuck in such a situation – between life and death, not alive, not dead, barely breathing but unable to live, as well as how it affects the loved ones around.

The title ‘A Train Crosses the Desert’ came to me by pure luck. I rediscovered Egyptian poet and journalist Ashraf Aboul-Yazid’s compilation ‘The Memory of Silence’ which he had gifted to me a year prior and started reading it. Two poems ‘A Prison’ and ‘A Train Crosses the Desert’ struck me emotionally. Reading the poems, again and again, was an experience that’s hard to describe in words. As with all art, it’s best to experience the artwork than talk about it because no other words or explanations can do justice to it.

I wrote, directed and co-produced the film in collaboration with Goethe-Institute Pakistan and Institute of Business Management (IoBM) and by the end of 2020, the train had finally left the station when it started getting accepted into film festivals in the US, India, Mexico and Turkey.

It was then we realized it was, to the best of our knowledge, the first Sindhi-language film in the history of Pakistan to make it to international film festivals. After seven festivals under our belt, including Jaipur International Film Festival (India), South Asian International Film Festival (NYC, USA), Muestra Itinerante de Cine (Mexico) and others, we finally came to the 17th Kazan International Muslim Film Festival in Tatarstan, Russia in September 2021.

I consider showcasing a Sindhi film in Russia an accomplishment as I don’t believe the Russian and Tatar audience would have ever experienced a film in this language. It’s not just a personal accomplishment but rather that for an entire people.

The films were selected for the main program by a commission led by Gulnara Abikeeva, Kazakh film critic and the president of the Association of Film Critics of Kazakhstan. Among 50 films selected for competition from among hundreds, only one was from Pakistan, and that too was in Sindhi. This is an unforgettable honor.

Kazan was also special because it was the first film festival I attended as a filmmaker (thanks to the pandemic, I had not been able to attend the festivals on-site throughout the year). Previously, I had only been to film festivals in Pakistan and Korea as a journalist, jury member or a panelist. Getting to be on the other side of it was a bucket list item that I finally got to check off.

In Kazan, the reception to the film was wonderful. I sensed a curiosity about this wonderful 7000-year-old Sindhi culture and language from Tatar audience as well as media. While my presence and words served as representatives of Sindh, I credit the film’s team – from crew to the cast and the poet Dali (whose English-translated Arabic poetry was further beautifully translated into Sindhi by my father Nasir Aijaz) – who truly represented the culture.

It was through the enigmatic and heartbreaking performances delivered by Tariq Raja and Nadir Hussain, as well as Arshad Shaikh; the hypnotic sound design by Omer Naeem and Syed Basit Amrohvi, and the dark, drenched-in-gold visuals by Ali Sattar that Russia truly got introduced to Sindhi cinema.

Now I say Sindhi cinema, but it really doesn’t exist on any scale. Hence, the film becomes even more important for me, as I intended it to be the first step, a launchpad that we can use to set the foundations of what may possibly become Sindhi cinema in Pakistan. It may take a year or a decade or two, who knows, but the platform Kazan International Film Festival provided brought more eyes to our Sindhi short film.

And while the film is called ‘A Train Crosses the Desert’, and the desert of Sindhi cinema we have to cross is vast and endless, it will for long be associated with the three rivers it reached – from Indus (Sindhu) to the Nile and finally to Volga. And as the train crosses more deserts and rivers, the songs of Sindhu and the Nile, and the songs of the Volga shall keep echoing throughout the journey.