The Indian Farmer Protests: An overview of the world’s biggest sit-down protest happening in India right now

Protesting farmers

By Gunjeet Sra*

NEW DELHI: On June 3, 2020, the Indian government announced that it would be introducing new agricultural ordinances in favour of farmers. The Agricultural Minister, Narendra Singh Tomar called them a “a historic-step in unlocking the vastly regulated agricultural markets in the country.” A month later, protests against the said ordinances began to take steam, but the government refused to back down.

The bills were passed in the parliament in September 2020.

By November 26th, the protesting farmers, led by the northern state of Punjab and some 30 farm unions from across the country were marching towards the capital, New Delhi. The demand was to repeal the laws.

It is the David Vs Golaith moment in the Indian democracy, with over 400 thousand farmers participating in the sit down protests. Almost 90 days after they first started, the government is yet to rescind the laws but what started as an agitation against the protesting laws has now taken form of an agricultural revolution that has farmers occupying borders surrounding the national capital of Delhi.

Talks between the government and the farmer leaders have yielded no results. The government has offered to tweak the laws or put a hold on them for 18 months. But the farmers don’t want a compromise, they want a repeal.

For now, both parties remain in a standoff.

protesting farmers

Who is the Indian farmer?

On paper, the Indian farmer is a powerful political asset, in the face of increasing modernisation and changing times, India still relies heavily on its agricultural sector to determine its elections. 83.5% of seats in India’s lower house of parliament are in rural areas. Nearly 60% of the country is involved in the agriculture sector out of this 85% of the farmers are poor or marginalised.. 18% of India’s GDP comes from agriculture. The Indian farmer has seen little improvement in his circumstance since the 1960s, almost 52% of agricultural families continue to be under heavy debt resulting in a large number of farmer suicides across the country. Despite dominating the electoral vote bank, the Indian farmer feels let down by the government, who they feel is short-charging them and doing little to help their circumstance.

What are the new Indian agricultural reforms?

The new ordinances that the government has proposed aim to introduce a free market into a state regulated one. The laws will essentially allow private buyers to not only buy directly from farmers but also hoard essential commodities for sale later. In india, the hoarding of essential commodities was deemed illegal and only government authorised agents had the permission to do so. Most of the Indian farmers also sell their produce currently to government regulated wholesale markets with assured floor prices. The new laws also outline ground rules for contract farming. Currently the farmers rely on the government regulated markets to sell their produce locally. It is a carefully regulated market space and the new laws give the option to farmers to sell anywhere across the country, outside this marketplace.

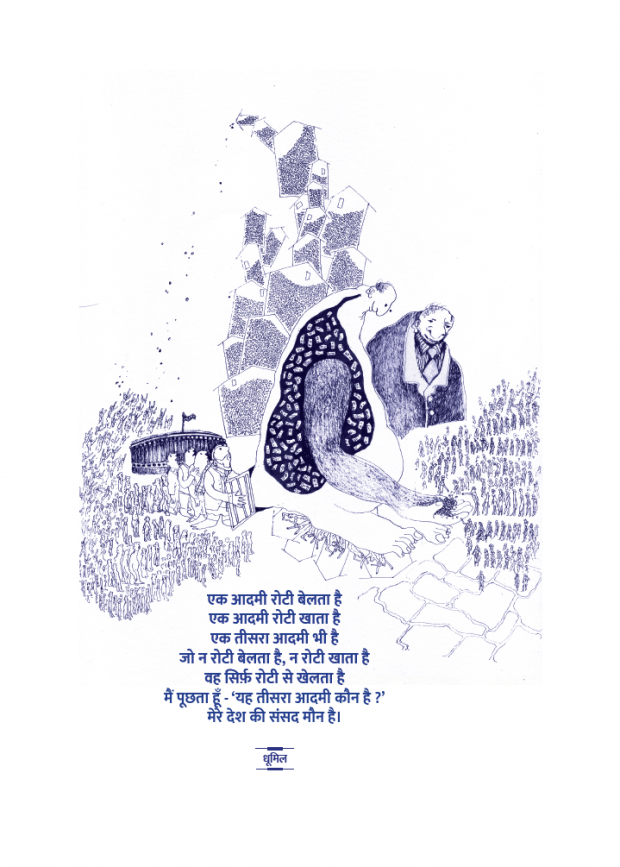

An illustration from the latest edition of the newspaper, Trolley Times

Why are the farmers protesting?

The biggest grievance that the farmers have at the moment is the fact that these laws allow no room for government regulated floor pricing. The farmers feel this will result in large scale exploitation by private players and they will eventually be forced to sell their produce at throwaway prices, which will have dire consequences for the already burdened farmers. In reality, there are some states in India that do allow for direct sale to private players but they have to guarantee a minimum floor price. The government, in its talk with the farmers is assuring regulated floor pricing but the farmers are not convinced as the government is unwilling to put it as a specific clause in the bills. The farmers fear the collapse of the government regulated market system will leave them with no backup option to safeguard their interests from private players. Another point of contention is the contract farming clause, the new laws mention that, in case of a problem with the contract, the farmer cannot approach a court to settle the dispute and must rely on local administrative authorities to solve the problem. The farmers believe that this clause leaves them further vulnerable.

The front page of Trolley Times, a newspaper launched for the farmers protest by volunteers at the protest

Human Rights Concerns

Earlier this month, the protest sites were barricaded with barbed wires and spikes in a bid to isolate the protestors after violence broke out in the capital. Heavy police deployment and unease of access has made it difficult for the public, as well as the media to access these protest sites freely. But despite this, the farmers continue to rally forth. Relying heavily on community media via social media, the protesting farmers are controlling their own narrative, launching both, their own newspaper and their official social media channels to access information from.

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) has condemned the violence against protestors where authorities used tear gas, water cannons and police batons to stop protestors from entering the capital.

HRW also stated that press freedom in India needed to be protected in context of cases against 6 senior journalists who have been charged with sedition and promoting communal disharmony after they covered the protest march which turned violent on 26th January in Delhi.

On January 30, the Delhi police also detained two journalists, Dharmender Singh and Mandeep Punia while they were covering the protests. The police alleged that Punia had “misbehaved” with them. Singh was released immediately but Punia remained in custody and was released after 14 days.

The police has also filed cases of attempted murder, criminal conspiracy and rioting against 37 farmers union leaders and activists. The police allege that they were made after inflammatory speeches and their involvement in violence. Most of the people named in these cases are involved in talks with the government over the farm bills and have openly pledged to be non-violent.

Women farmers sit in solidarity at one of the borders (Tikri) surrounding New Delhi

From Justin Trudeau, to Greta Thunberg to even Rihanna, international figures have expressed concern over the ongoing protests. The Indian government has responded to all these concerns by deeming the matter to be “internal” and of national interest alone. And being committed to solving it. After Greta Thunberg shared a toolkit on the farmers protest, the National Intelligence Agency arrested 22-year-old environmental activist Disha Ravi from Bengaluru for making the google document which was later shared and then deleted by Thunberg. Ravi has been charged with sedition and conspiracy, along with Shantanu Muluk, who helped create the document.

There has been massive outrage after her arrest but the Delhi police is defending its actions and stating her arrest has been made in accordance to law.

- Gunjeet Sra is a New Delhi-based reporter and columnist. She is also the editor of sbcltr, an interactive multimedia platform aimed at giving the subaltern a voice.