Unesco culture heritage honour for Singapore hawkers

By Ivan Lim

Former AJA President, Contributor to AsiaN

SINGAPORE: For India it is yoga, Thailand it is traditional massage, and South Korea it is kimjang, or the art of kimchi making and sharing. In the city-state’s case, the Unesco honour has to do with its hawker culture finding a place on the Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

The 584 listed items of 131 countries included Indonesia’s batik making, Malaysia’s dongdang Sayang and tugging ritual and games of Cambodia, Philippines and Vietnam as well as whistled language of Turkey, tahbeeb stick game of Egypt and Couscou recipes and tradition of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Mauritania.

This refers not only to the folksy food vendors, a common sight in Asian cities, but also the traditional multi-ethnic cuisines that bring delight and are becoming a way of life.

Unesco has given recognition to the Republic’s hawker culture in December as a mirror of its evolution as a model of urban society where its Chinese, Malay, Indian and other citizens enjoy community dining and the ethnic cuisines.

Amid the gloom cast by the year-long Covid-19 pandemic, Singaporeans, and especially the humble food vendors, have found something to lift up their spirits. They made merry during the Dec 26 to Jan 11 SG Hawkerfest with treasure hunts and online quizzes in which winners received vouchers to buy food from participating vendors.

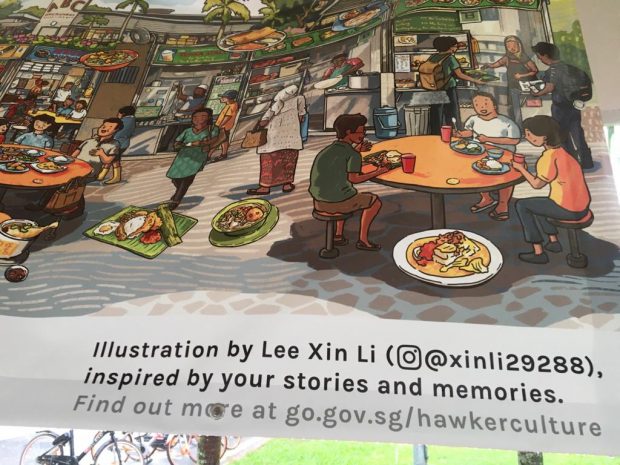

Publicity-wise, banners went up in housing neighbourhoods, depicting painted scenes of smiling hawkers dishing out food and drinks from their individual stalls. The denizens of the food trade, who clock 12-to-16-hourdays, have good reason to be happy that at long last their life-long work has received due attention and recognition internationally.

Further, Singapore is now obliged to tell Unesco every six years what it is doing to promote hawker culture for future generations.

The Unesco listing for hawker culture came a time when an aging core of food vendors is hanging up their woks for good. Few, if any, of their children are keen to take over and continue the trade owing to the long hours in cramped cubicles and low earnings.

Public calls have led to various initiatives to help attract young generation to carry on the hawker tradition and preserve the secret recipes of cuisines. The authorities have rolled out a number of training programmes and financial incentives.

Since 2013, the median age for new entrants to the hawker trade has been lowered to 46. Fifty-nine is still the median age for hawkers.

Thanks to the enduring hawkers, eating out is the norm for the work-a-day Singaporean – the Ah Beng (Chinese), Ahmad (Malay) and Murali (Indian) – beginning with breakfast at the coffee shop/tea kiosk before going to office; savouring local noodle or rice meal during the day’s one-hour lunch; and buying dinner home after work. All three meals a day are served up by hawkers.

By taking over the chore of home-cooking, hawkers have, willy-nilly, shaped the eating habits of the busy Singaporean from all walks of life.

“Why cook when I can get good food from so many different hawker- chefs,” said Samuel Sim (not his real name), a doctor-friend of mine.

As unsung heroes, the humble hawkers’ services in satisfying stomachs are part and parcel of the story of the republic’s progress from Third World to its First World status.

“Hawker food makes Singapore unique. It is part of our national identity,” said Ambassador-at-Large Professor Tommy Koh.

“I must say that my wife and I are great fans of hawker centres. We go to the wet market every week. We often have lunch on a Sunday or Saturday in one of the hawker centres.”

At the launch of a new book entitled Fifty Secrets of Singapore’s Success, he lauded the service of hawkers who “saved’’ Singapore by providing low-cost meals. These do not attract the 7 per cent GST (goods/service tax).

Local hawkers have not had a breezy beginning. Their roots can be traced to poor migrants escaping the poverty and chaos of war and upheavals in China and the region. Dramatic scenes of unlicensed itinerant and pushcart hawkers fleeing truncheon-waving police constables are a staple of TV dramas portraying the life of Chinese immigrants from Chinese provinces of Fujian, Guangzhou and Hainan to Nanyang or South Seas, including the then British colony of Singapore.

With the advent of self-government in 1959, and independence in 1965, the Singapore authorities sought to shift street hawkers off the streets in the interest of public hygiene and to reduce road congestion. The exercise involved housing hawker indoors and licensing them.

Those who opted for change were each allocated a kitchen stall complete with electricity and gas as well as piped water to prepare their dishes. Common seating places added to the convenience of customers who dine in or buy food home.

Hawker delicacies include traditional family recipes or the signature fare of a particular ethnic or dialect group – for example, the popular Hainanese chicken rice (Hainan province, China) or the chicken or mutton Biryani rice (India), or the Nasi lemak (Malaysia/Indonesia).

The first hawker centre was built in 1970. It has come a long way with hundreds more mushrooming in housing estates in keeping with Singapore’s urbanisation. These non-air-conditioned joints have become what Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong described as community dining facilities, where residents eat and chat animatedly- noisy to my dining pal Hiren Phukan but a vibrant atmosphere to others to liven up bonds – forming a unique winning combination that impressed Unesco.