South Korea: Pressure, challenges facing disease detectives battling coronavirus on front lines

This photo, provided by the Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (KCDC), shows Park Young-joon, a head of an epidemiology and case management team under the KCDC’s central disaster headquarters set up to tackle the new coronavirus, on Feb. 12, 2020. (Yonhap)

By Kim Seung-yeon

YONHAP

Seoul: Disease detectives, like coronavirus investigator Park Young-joon, see many similarities between what they and criminal detectives do. Both are deployed as soon as new cases occur, talk to affected people and investigate scenes.

But one of the biggest differences may be the time pressure that germ investigators work under to determine the extent of contact of infected people from verbal statements, surveillance video, credit card use and other sources.

Extra pressure comes from persuading patients to tell the truth and exposing themselves to infection risks.

“We need to get the field investigation done as accurately as possible within the first 24 hours of the dispatch or by the next day. We’re pressed for time,” Park, a chief disease detective at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), said.

“And because we don’t exactly know about the nature of this type of new virus yet, we’re compelled to make decisions fast, like in terms of advising the extent and degree of quarantine measures and determining who should be put into isolation,” he said in a recent interview with Yonhap News Agency.

South Korea has been rattled by the outbreak of the new coronavirus, which originated in the Chinese city of Wuhan, since it reported the first infection case on Jan. 20. The fact that the virus’s spread is so fast and there is no proven vaccine or treatment has heightened fear among the public, with people scrambling to hoard boxes of face masks and canceling all outside events and activities. Schools suspended classes, and large retail stores closed for several days.

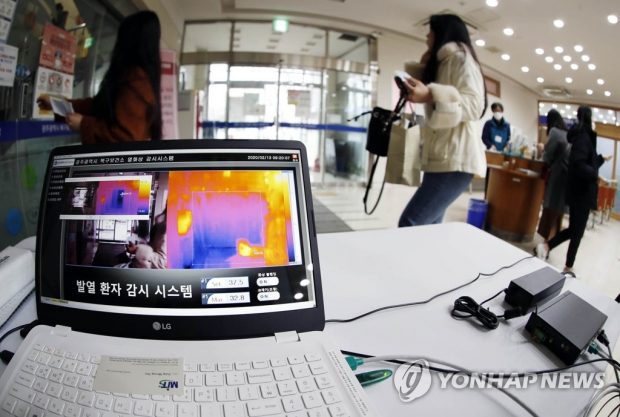

A fever-detecting device is in place on a desk in a public health center in the southwestern city of Gwangju on Feb. 13, 2020, in the photo provided by the Gwangju Buk-gu Community Health Center. (Yonhap)

The situation has taken a turn for the worse this week. Health authorities confirmed the first death from the virus Thursday, declaring the start of community spread. The number of infections rose to 156 as of Friday morning, a surge by more than a fivefold from Monday’s tally.

But despite the onerous time pressure, Park, 43, said the job of epidemiological intelligence service officers (EISO) is meant to be about enduring the inevitable long process that requires scientific judgment based on objective evidence, and often a bit of human touch, though it may not be so easy at the beginning.

Park, a preventive medicine specialist at the KCDC, is currently leading an epidemiology and case management team under the KCDC’s central disaster headquarters set up to tackle the new virus. Including the workforce in provinces, there are about 130 field epidemiologists in Korea.

When an infection case is reported, a group of five to 10 EISO officers are immediately deployed to the scene to carry out an epidemiological survey.

The survey involves interviewing patients to establish a timeline with places that they visited and whom they may have had contact with.

The timeline is then cross-checked against surveillance footage from the cited locations to see if the statements add up. The patients’ credit card and mobile phone records are also instrumental in verifying the patients’ stories.

This is the part where “doing things quickly” no longer works.

“You’d be surprised how tedious the work gets when you have hours worth of surveillance footage to go through,” Park said. “In one case, it took us nearly two days scouring the footage to sort out people that had made contact with the patient.”

That patient had already visited a few hospitals for respiratory problems and was belatedly declared positive for the virus. Park’s team had to go through nearly a week’s worth of surveillance footage.

The “contact tracing,” as Park explains, refers to tracking down everyone with whom the infected person has had face-to-face contact within a distance of less than two meters.

Identifying whom the patient has had contact with is vital to building the grounds for determining the scope of quarantine.

“It’s time-consuming work, but it’s something that we can never do in a hurry. We can’t afford to miss anything,” he said.

Such persistent efforts are also required when the officers have to persuade patients to share personal information like the places they went and what they did.

A public health official sterilizes the emergency room of the Korea University Medical Center in Seoul on Feb. 16, 2020. (Yonhap)

Many people express displeasure at being treated like a criminal suspect and refuse to disclose details, claiming privacy rights.

“One thing I always remind myself and my junior colleagues to tell the patients is that we’re not monitoring them to punish them, not putting them under isolation to restrict them, but to protect them and their loved ones.”

Some delay in the investigation process may be inevitable, but persuasion has rarely failed as long as he recalls that basic guideline.

So however daunting the daily tasks are, it’s about seeking a balance between measuring up to the soaring public demand for quick responses and sticking to principles.

That’s why the bottom line is to play it by the book, according to Park.

“We try to stay focused on what we are professionally capable of. It’s like going back to the traditional image of a detective, holding a magnifying glass and following the footsteps of the culprit,” he said. “Except that we follow germs.”

YONHAP