How Korea’s modern art began

Exhibition sheds light on art of Korean Empire

The Korean Empire (1897-1910), proclaimed by Joseon’s 26th ruler King Gojong as an effort to modernize, is often neglected in Korea’s history. “Art of the Korean Empire ― The Emergence of Modern Art,” an exhibition on view at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Deoksugung, sheds light on this short-lived, but crucial period in the development of modern art in Korea. The exhibit commemorates the 20th anniversary of MMCA Deoksugung, situated within one of Seoul’s royal palaces.

“The art of the Korean Empire is the legacy of King Gojong. Despite its relatively brief duration, the foundation for Korean modern art of the 20th century was laid during the Korean Empire,” MMCA curator Bae Won-jung said. “It was a dynamic era with a lot of cultural stimuli when foreign influences were rejected while preserving traditional practices.” The art history of the Korean Empire has not yet been studied adequately, but this exhibit aims to provide a starter for a proper understanding of the beginnings of Korean modern art. “The Korean Empire spanned only 13 years, but we organized the exhibit with works from 1890, when King Gojong started to pursue modernization, through 1926, the year King Sunjong, the second and last emperor of the Korean Empire, passed away. Most research on Korean modern art begins from the 1930s, but this exhibition highlights how modern art was shaped right at the start of 20th century Korea.” Bae said. The exhibit features over 200 pieces, from court paintings to photography and craftworks to give an in-depth look into the art of the Korean Empire, divided in four sections ― “Art of Empire,” “Photography: New Method of Documentation and Representation,” “Crafts: Artistic and Industrial Paths” and “Painting as Art and Painter as Artist.”

Court art accepted new culture while preserving traditional values

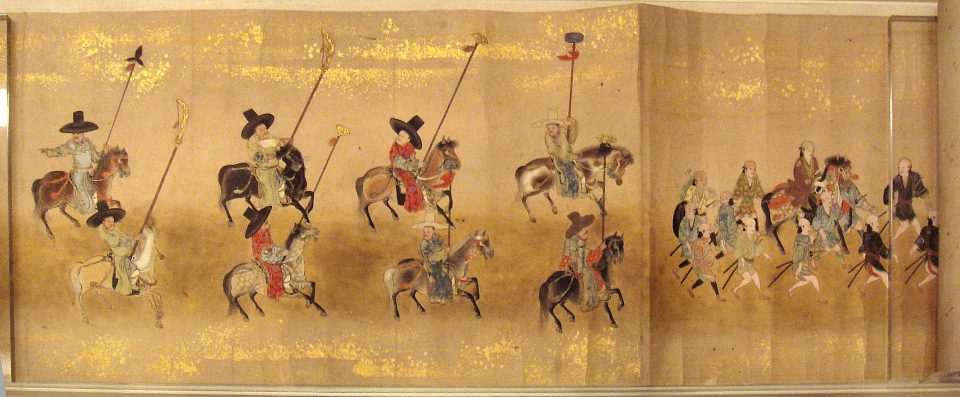

The first part showcases how court art adapted modern influences in style. Upon the declaration of the Korean Empire, conservative court art indicated a change in style as the status of the ruler was elevated from king to emperor, including the yellow robe. Court documentary paintings in “uigwe,” or royal protocols, also reflected modern elements as the society went through changes. The “Formality Manual from the office in charge of drawing or copying Royal Portraits of the Kings” documented the process of restoring seven royal portraits lost in a fire. A 10-panel folding screen depicts a ceremony for the crown prince, who later becomes King Sunjong, after recovering from smallpox. The highlight of the section is “Cranes and Peaches,” a 12-panel folding screen with bright colors and gold leaf. This lavish folding screen is different from the traditional Korean style. “This screen is estimated to have been created in 1902, which coincides with King Gojong’s celebration for entering ‘Giroso’ (hall of venerable officials). Different styles coexist in this folding screen as court painters adopted new pigments and used them together with traditional methods,” curator said. Modernity even affected Buddhist paintings. A 1907 “Buddhist Deities” painting features guardian deities in military uniforms of the Korean Empire.

“The appearance of soldiers in modern attire in Buddhist paintings shows strong wishes for protection from the emerging new powers.” “Photography: New Method of Documentation and Representation” shows how the new technology gradually replaced royal portraiture and documentary paintings after being introduced to Korea in the 1880s. However, back then, photography did not fully develop into an artistic genre, but a supplement to paintings for its characteristics of accurate depiction. “The hyperrealistic photography complemented painting and royal portraits were substituted for photographs. The King and the royal family were documented through photogenic portraits and their images were reproduced in other media such as postcard as the king’s image was consumed to promote the change to a modern state,” the curator explained. “It is also notable that female members of the royal family were also photographed . A portrait of King Gojong from 1918 is assumed to be painted based on a photograph of the king. Unlike traditional royal portraits, colorful drapes on the backdrop and robe indicate use of a Western shading method.

“This painting used traditional paint, but employed new techniques. It is assumed to be shared within the royal family ― it is said that King Yeongchin, son of King Gojong, kept this portrait when he lived in Japan. Yi Bang-ja, wife of King Yeongchin, remembered the painting at her home,” the curator said. King Gojong liked to be photographed and left a variety of photographic records. A portrait of King Gojong, taken by royal photographer Kim Kyu-jin and gifted to Edward Henry Harriman, an American railroad magnate who visited Joseon in 1905, is displayed with its linden wood storage box. Photos also replaced documentary paintings. Instead of painting national events such as the funeral of royal family, photographers captured the moments and it was published through media outlets inside and outside Korea. “Crafts: Artistic and Industrial Paths” presents how artists accepted new culture while preserving traditional Eastern values. “Korean traditional craft could have been developed into unique modernity if it were not for the Japanese colonial rule of Korea. Crafts were mostly handled by the Craft Workshop established by the royal family until individual craftsman started to be noted,” the curator said.

The Hanseong Craft Workshop ran from 1908 to 1913 and changed its name to the Craft Workshop of the Office of the Royal Household (1913-1922) and the Joseon Craft Workshop Inc. (1922-1936). The changes in the title demonstrate the shift from government-led handicrafts industry to modern style crafts industry. Artists produced exquisite embroidery works as well as fine art quality craftworks using traditional materials such as metalwork, ceramics, woodcraft and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The Craft Workshop was criticized for commercializing the royal emblems of the Korean Empire, but it played an important role in establishing craft as fine art and establishing the idea of design in craft in Korea.

During Joseon era, the Royal Bureau of Painting took charge of producing all paintings for the royal court. However, the bureau was abolished in 1894 by King Gojong and outside artists started to take part in court paintings. Unlike previous anonymous royal artworks, these new court painters left their name with their works, showcasing creativity. Notable court painters during the Korean Empire include An Jung-sik, Cho Seok-jin and Kim Kyu-jin and they became pioneers of Korean modern art by establishing the Calligraphy and Painting Society and the Calligraphy and Painting Research Institute to train new artistic talents. Chae Yong-shin’s “10 Symbols of Longevity” features plants and animals portrayed in Western perspective and its realistic depiction differentiates from traditional auspicious painting style. The exhibit wraps up with a media art piece inspired by the wall paintings of Changdeokgung Palace by artist Lee Mee-jee. A three-channel video “Embracing the Last Court Paintings of the Korean Empire with Light” takes visitors to the final court paintings of Joseon that adorned the royal palace.

By Kwon Mee-yoo

(Korea Times)