Neglected No Longer: Washington Returns to Central Asia

Central Asia is not, and has never been, a United States foreign-policy priority. Neither will it displace the importance of other regions to Washington anytime soon. Moreover, numerous analysts discount it as a promising area for expanded attention. Indeed, they expect US and European presence and influence there to decline as Chinese and Asian influence grow. But the administration of US President Donald Trump has different ideas and clearly seeks to boost US and allied influence in Central Asia. Therefore, it is increasingly signaling in both word and deed that Central Asia figures more prominently than before in American foreign policy calculations. This is to be welcomed, especially if the Trump administration rejects the view of the Barack Obama administration prior to 2015 that Central Asia’s importance lie only in its proximity to Russia, China and Afghanistan. Only in 2015 did US Secretary of State John Kerry institute a regularized 5+1 process among Central Asian foreign ministers and the Secretary of State. While that is constructive, it hardly denotes a real policy or serious thinking. Neither does it reckon with the major changes occurring in Central Asia that merit attention.

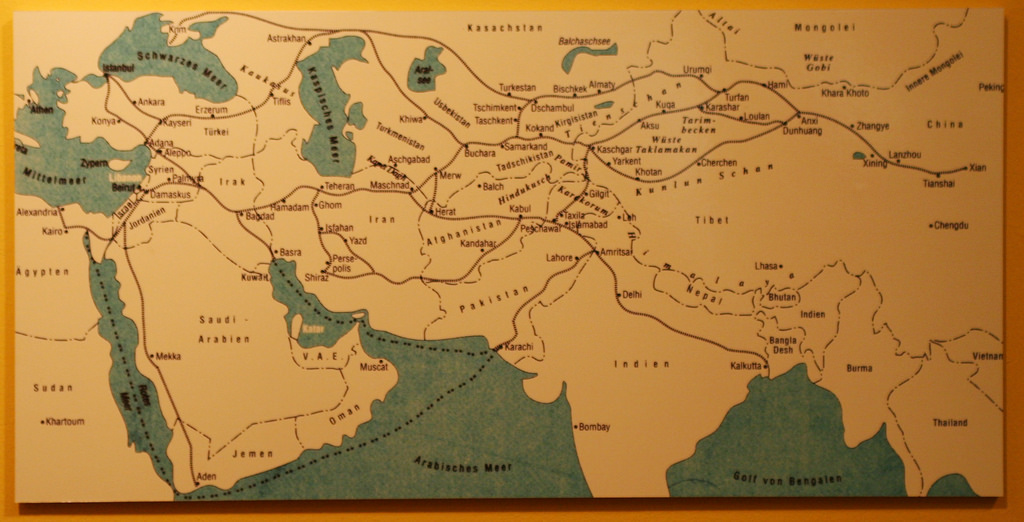

Five specific recent developments could be harbingers of impending change in US policy. First, the recent suspension of military aid to Pakistan for failing to restrain terrorists whom it has organized and supported. This triggered warnings that Pakistan might retaliate by striking at or banning the use of its territory as the logistical tail for US forces in Afghanistan. If Islamabad does so, then it will become necessary to reconsider the previous route of the Northern Distribution Network (NDN) through the Caucasus and Central Asia (obviously, Russia will not play the same role here that it did in 2009-10). That reconsideration inevitably raises the issue of sustained US economic assistance and development projects with local governments and potentially the question of direct military assistance, as happened while the NDN functioned. Newly enhanced military and economic ties could lead policy-makers to see the region as self-standing in its own right, not as an appendage defined by its proximity to some other major issue.

Of course, that perspective does not mean ignoring Russian and Chinese involvement in Central Asia. But here, too, there are signs, at least rhetorically, of enhanced US interest in Central Asia. If anything — and this is the second potential harbinger of change — the Trump administration has clearly indicated to India, Japan and China its opposition to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It has just proclaimed its vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific that implicitly encompasses and will attempt to integrate with Central Asia, given the growing intimacy between India and Washington. This vision involves large-scale private and public investments to enhance connectivity and foster a more liberal international economic order — not the closed bloc that China’s BRI envisages.

Indeed, the third factor driving US policy and the opposition to China stems from the Trump administration’s emphasis on using economic means to advance American policy interests abroad. During Trump’s visit to Japan in November 2017, he and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe unveiled a plan to counter China’s BRI in Central Asia. This statement built on blunt critiques of the BRI by US Secretary of Defense James Mattis and then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and was prefigured in the communiqué of Trump’s meetings with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. So, clearly this is part of a larger Indo-Japanese-American effort against China. At their meeting, Modi and Trump said that they “…support bolstering regional economic connectivity through the transparent development of infrastructure and the use of responsible debt financing practices, while ensuring respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, the rule of law, and the environment; and call on other nations in the region to adhere to these principles.”

At their joint press conference, Abe personally stated his commitment. “I am determined to see to it, so that both Japan and the US strongly lead the regional and, eventually, the global economic growth by our cumulative efforts in creating fair and effective economic order in this region.” Since then, and following his intention to enhance Japan’s global role while countering China, Abe “has been very active in proposing an alternative to China in general and the Belt and Road in particular.” Moreover, Japan’s activities here, which clearly enjoy Washington’s support, also include India in a growing strategic partnership to develop power plants, railroads, port facilities and other infrastructure in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, the Indian Ocean islands and Bangladesh. Given the scope of this Indo-Japanese alignment, we should also expect to see these two parties co-operating against China and with the US in Central Asia.

A Joint Vision

Thus, Washington, New Delhi and Tokyo have criticized Chinese policy as objectionable and in some sense a threat to Central Asian states. And they have announced concrete programs to counter the BRI in Central Asia. While Central Asia is an area of growing interest to Japan and India, this announcement marked a departure for the US, which under the last two administrations had little regard for Central Asia as a venue for major investment and trade programs, especially together with US allies. But this does not appear to have been a rhetorical one-off for the Trump administration.

Instead, American support is crucial to backstopping Japanese and Indian policies for Central Asia. In their joint summit, Abe and Trump announced programs to implement this vision, and the new Indo-Pacific vision builds on this. The Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) agreed with Japanese partners “to offer high-quality United States-Japan infrastructure investment alternatives in the Indo-Pacific region.” OPIC’s own read-out stated that it and the Japanese banks involved had a shared “commitment to tackling development challenges and bolstering investment in infrastructure, energy and other critical sectors throughout Asia and the Indo Pacific, the Middle East, and Africa.” Both sides announced a shared initiative to provide universal access to affordable and reliable energy across Asia, while the US Trade and Development Agency will work with Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) to support public and best practices in infrastructure projects in third countries and emerging markets. This clearly challenges not only the BRI, but also the Chinese-sponsored Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) that funds its projects in the BRI.

All these initiatives explicitly target the BRI for its defects regarding transparency and monopolistic practices to advance Chinese interests above all others. Indeed, there are numerous signs of mounting resistance in Central Asia and globally to Chinese investment plans for their lack of transparency, China’s high-handed and pressuring behavior towards recipients and the realization that these projects will remain under Chinese control, not their own. We have long known that Central Asians are by no means enamored of China and what they perceive as a Chinese takeover of their lands and/or economies. So, this is not a wholly unexpected development. Indeed, signs of resistance to China continue to appear in Central Asia. China’s increasingly high-handed behavior, with mounting evidence of economic coercion, interference in domestic politics and encroaching military aggrandizement is as discernible there as elsewhere. Signifying its growing power, and belying past statements of its pacific intentions toward Central Asia, China now seeks a military base in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Undoubtedly, China wants to guarantee its investments in Central Asia while also projecting power abroad. Indeed, China has already encroached upon and annexed Central Asian territories, notably from Tajikistan, which could not resist. And this well-deserved suspicion of Chinese aims clearly opens doors to Washington, Tokyo and New Delhi. Moreover, cases where excessive debt has prompted Chinese takeovers of critical infrastructure — for example, Hambantota port in Sri Lanka — have raised a red flag across Asia.

Pushing Private Markets

Washington’s new policies also reflect the Trump administration’s commitment to private markets over government deals. For example, in meeting Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Trump both noted his interlocutor’s reform efforts and also discussed with him opportunities for enhanced bilateral co-operation with regard to Afghanistan, stating that reforms will set the stage for improved trade and investment. Since Mirziyoyev is doing everything in his government’s power to increase foreign trade and investment beyond Russia and China, it is very likely that these conversations touched on specific projects and programs whereby both states could step up their economic co-operation and enhance the US profile in Uzbekistan and Central Asia more generally. Indeed, those talks generated US$5 billion in over 20 deals and could unlock many future deals as well.

Further confirmation of the US administration emphasizing a trade and investment approach to Central Asia may be found in the fourth example of its enhanced interest. Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy explicitly and quite unprecedentedly referred to Central Asia, although most observers overlooked this. Not surprisingly, this section of the strategy explicitly invoked the threat of terrorism. But it also, openly attacked the Russo-Chinese effort to limit Central Asian states’ de facto independence in foreign policy. Thus, it stated, “And we seek Central Asian states that are resilient against domination by rival powers, are resistant to becoming jihadist safe havens, and prioritize reforms.” Clearly the themes of the meeting with Prime Minister Abe are here, along with the obvious priority of terrorism, preventing Russian and/or Chinese domination, and enhanced use of economic instruments of power. Indeed, the security strategy openly supports Central Asia’s economic integration with South Asia, not Russia or China. The strategy also states that the US “pursues economic ties not only for market access but also to create relationships to advance common political and security interests and directly attacks Russia’s efforts to use energy projects to project its influence through Europe and Central Asia.” Thus, the US State Department has again supported a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline and the Southern Gas Corridor from the Caspian Sea to Europe, projects that become more conceivable since the littoral powers recently signed an agreement that now allows for the building of a trans-Caspian pipeline. As a result there is a prospect for establishing a legal regime for demarcating the Caspian Sea and building a gas pipeline across it to Azerbaijan and Europe.

The Emergence of a Policy

These are hardly coincidental or accidental statements. Rather, they indicate a consistent approach over several venues, such as the meetings with Abe and Modi and the conversations with Mirziyoyev and Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The security strategy, when speaking more generally about the developing world, again emphasizes the economic aspect. In discussing Africa, Asia and Latin America, the document forthrightly asserts that US investments remain the “most sustainable and responsible approach to development,” and starkly contrast with authoritarian governments’ development offers, i.e. those of Russia and China. In this context, the security strategy also states that Washington will modernize investment and trade tools for these countries so that it can compete with other states that use project finance and investment to advance their interests.

Finally, the fifth element of the strategy connects the overall need for economic development and enhanced US-Central Asian ties with what appears to be incentivizing Central Asian states, notably Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, to promote both enhanced economic ties with the US and solutions to the war in Afghanistan. These themes emerge from Trump’s contacts with the presidents of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. US officials as well as Trump himself have hailed Uzbekistan’s reforms. Foreign analysts see Washington’s renewed commitment to the war in Afghanistan as forging stronger ties with Central Asia against China, Russia and terrorism to give Afghanistan “strategic depth.” And Uzbekistan is apparently equally receptive to possibilities for expanded US investment through logistical support for the war and its overall economy.

In line with its own interests and reforms, Uzbekistan has now become more active over Afghanistan. Tashkent and Kabul are discussing joint projects such as railway and electricity lines and have restored direct flights between the two, while also discussing plans for new consulates in Uzbekistan. The two governments are discussing a joint regional security commission under American supervision that has already led to the creation of the C5+1 format between Central Asian states and Afghanistan that will be an effective platform for discussing regional issues such as the 5+1 format for talks with the US. In late March, Tashkent hosted a conference involving regional powers, Russia, China, the US and others to try to determine how to bring the Taliban into direct peace talks with Kabul. This continues the so called Kabul process launched by the Afghan government in opposition to Russo-Chinese initiatives that support Taliban inclusion in the Afghan government and towards which end Moscow has been supporting the Taliban since around 2013.

Kazakhstan’s Role

Regarding Kazakhstan, we see similar developments. The US has allayed earlier Kazakh fears that it will suffer from the sanctions imposed on Russia and indicated that visa-free travel to the US is still possible. During President Nazarbayev’s visit to Washington, Trump hailed the “tremendous” economic relationship with Kazakhstan and thanked it for its support for the US mission in Afghanistan. Their personal relationship was apparently highly congenial, and in a joint statement both presidents reaffirmed Kazakhstan’s independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity as well as Kazakhstan’s role in promoting global peace and prosperity. Nazarbayev even thanked Trump for defending Kazakhstan’s independence, clearly an anti-Russian statement given the constant presence of voices in Russia who would deny Kazakh statehood. He also said US-Central Asia ties benefited everyone, not least in the diffusion of investment and technology. Kazakhstan then also laid out an economic plan to assist Afghanistan, openly admitting this had been discussed with Trump and was in parallel to the military effort of the US. Concurrently, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to the UN, who was Chairman of the Security Council in January 2018, issued another UN statement in defense of Afghanistan, but this time firmly inserting Central Asia into the processes of improving border management, counter-narcotics initiatives, economic development and other issues.

After this visit to Washington, bilateral trade and commercial relations and military ties are also growing. Even more aggravating for Moscow, Nazarbayev flatly refused to accede to Russia’s demand to abolish the visa-free regime with Washington and established this regime without even notifying Moscow. When Moscow protested, saying that such a regime would allow spies to come to Kazakhstan and then utilize the visa-free relationship with Russia to enter Russian territory, Nazarbayev’s minister of foreign affairs immediately announced that introducing a visa-free regime for foreign citizens was a legitimate right of any sovereign state, essentially telling Moscow that Russia could no longer simply give Kazakhstan instructions. Finally, in the coup de grace, Kazakhstan granted the US access to the ports of Aktau and Kuryk to supply Afghanistan, bypassing Russia. This decision coincided with Kazakhstan’s efforts to develop Aktau through a “special economic zone” and its belief that the US is the key to the plan’s success, as well as the materialization of the earlier US Silk Road plan of 2011, which had largely remained only on paper. While Astana worries about US sanctions against Russia on uranium imports, the impact of this potential move is unclear at present.

Rhetorical but Also Coherent

Thus, we see a coherent US strategy emphasizing the war on terrorism while also giving greater rhetorical support and actually creating mechanisms for using American economic power and policy together with Japan and India. The new policy on a Free and Open Indo-Pacific may actually impart the resources needed to make these programs work. The signs are all encouraging. The themes of this strategy for Central Asia — fighting terrorism, blocking Chinese and/or Russian domination and using economic instruments to integrate Central Asia — are linked and articulated in formal speeches, documents and governmental consultations. It is equally clear that Central Asia is increasingly being envisioned as a region in its own right and may actually get some US presidential or at least sustained high-level attention, something that has not always been the case over the last 25 years. The emerging direction is something that many American analysts including myself and S. Frederick Starr, director of the Central Asia Caucasus Institute in Washington, have long been championing. And the new American policy also clearly supports genuine progress towards real regional integration, another positive development. Therefore, we may be confident in postulating that a genuinely new strategy toward Central Asia, although based on earlier themes, is coming into focus. While many US and Western analysts still dismiss Central Asia as an area of little interest for the US, clearly the Trump administration does not see things that way. Moreover, its activities have caught Moscow’s, and perhaps also Beijing’s, attention. Russia not only berated Kazakhstan’s policies, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov also said that Washington might simply be using the 5+1 format to play politics:

We hear that the US is inclined to abuse this format a bit and to promote the ideas connected with what was known under previous administrations as the Greater Central Asia project. As you may remember, the project was aimed at focusing all the plans involving Central Asia towards the south, towards Afghanistan, while keeping the Russian Federation out of it. I am sure that if this is really the case and if our American colleagues promote these plans at their meetings with our Central Asian friends, they will see the fallacy of these attempts, which are prompted not by the interests of economic development and the improvement of the transport infrastructure, but by sheer geopolitics.

This position is enshrined in the new convention on the Caspian Sea that apparently gives both Iran and Russia the right to express their concern over US use of Kazakh ports to transfer non-military cargo to its forces in Afghanistan.

Nevertheless, for the US and Central Asia the heavy lifting lies ahead, because the real question with any such strategy is the willingness and ability of its shapers to allocate the resources needed to make significant alterations in the face of multiple global challenges and emergencies. If the reality matches the rhetoric, then the Trump administration will have, indeed, made a meaningful advance and contribution to US interests. Moreover, this strategy is a promising way to assert both American interests and, more importantly, ensure the genuine independence and mutual collaboration of Central Asian states after years of neglect. As the war in Afghanistan clearly shows, we pay a high price for that neglect.

By Stephen Blank

(Global Asia)