-Bill Hill and the A-Maize-ing School Bus

Yoon Seok-Hee – The AsiaN Correspondent

Instead of taking a plane like I did in November, I decided to take a bus to Standing Rock. I found a bus through a Facebook rideshare page departing from the Bronx on the 1st of December.

The driver and owner Bill Hill, was born and abandoned in Upstate New York in 1945. Hill was on his birth certificate, but he has never known his parents. He didn’t know where Vietnam was when he was sent there either, after a series of foster homes he always felt unwanted in.

After the war he drank and did drugs for a decade before he “shivered for a week in a farmhouse in Montana” and quit the habit. Since then, he has been doing one thing after another, including running supply caravans to Cuba, Mexico, and now to Standing Rock.

The motley crew included five men—an Asian (me), a Mexican, a Black Jamaican American, and two White men, one of who was a gay Dane and another half-native Canadian—and a biracial Dakota woman. Our bus, a mid-engine Crown Supercoach, had the back seats taken out for some floor space. The “corny” school bus with maize and native symbols on it was loud on the road and attracted some encouraging honks.

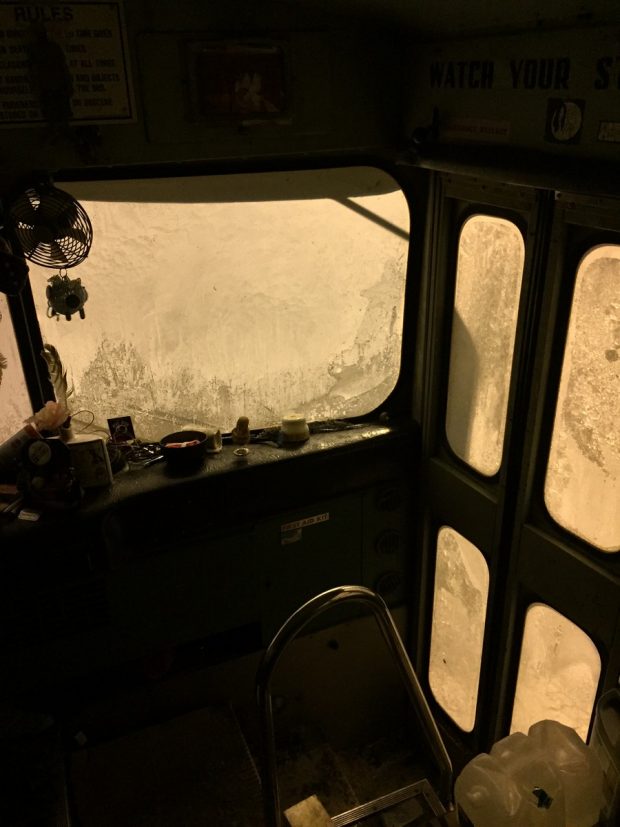

By the time the bus go out of Pennsylvania, we were already feeling cold, and by the second night in Iowa, the floor of the bus started to freeze at night. By the third night, when we arrived at Oceti Sakowin, the center of the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), we barely had time to erect a tent before the sun dropped, as the temperature did. Winter in the Dakotas was beginning.

-Oceti Sakowin Camp: The Seven Council Fires

First dawn at Oceti Sakowin was frigid. The winds never really stopped, and the campground, normally a summer grazing ground on a riverside meadow in the middle of the Great Plains, was completely exposed to the extremes. Despite this, the campers woke up at six to pray to the water by the fire and walked in procession to pray to the river by the water.

These ceremonies, which begins with burning sage, were not allowed to be photographed. One of the reasons why media was not welcome at the camp was the disrespect they often paid to Native customs about photography.

Men stood shoulder to shoulder in two lines down the frozen river banks and steadied the elder and younger women walk down to the river with blessed water and tobacco offerings. After the women prayed the women helped the men with the slippery ground.

We kept shouting “Mni Wiconi,” or Lakota for “Water is Life.” We shouted in different languages, in English, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, Russian, German, Swedish, in ASL and many others I didn’t recognize. The entire two hours a few hundred people lined up in pairs to pray and offer tobacco to the Cannonball—and the Missouri—River, we shouted Water is Life in unfamiliar languages, sang songs, and watched the Sun rise over the horizon.

-Veterans for Peace and a Victory…, for Now.

On December 3rd, the camp was in chaos with the influx of so many new “Water Protectors.” Organizations such as “Veterans for Peace” brought roughly 4000 veterans to Standing Rock. Citing the oath of enlistment, “to support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic,” the veterans brought teams of news media and cameras. The police, who had been steadfastly guarding the bridge, had magically disappeared.

The morning of the 4th brought more chaos. The camp was ordered by the North Dakota Governor’s office to leave by the 5th, and the veterans had vowed to “put their bodies between the Water Protectors and any forced eviction.”

The camp was forming up for a camp-wide prayer circle when the news came: The Army Corps of Engineers have denied ETP the permit for the pipeline, pending an Environmental Impact Statement and review.

The evening of the 4th was filled with song, dance, and fireworks, as every camper enjoyed the bit of celebrations. The coming snowstorm as well as the still-blinding halogen lights from the construction site tempered some of the excitement. As night fell, the winds grew.

-Snow Storms and Dakota Winter

On the 5th, snow was piling up and the winds went up to 50 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour). Our tent was sagging from the snow on one side and too many vehicles were stuck spinning on the side of the road.

I had started working at one of many kitchens around camp and was wrestling with frozen water and food ingredients. Inside the kitchen tent, it was relatively warm with the burning wooden stove at -5 Celsius (23 F), but outside felt like -20 C with the wind chill.

The port-a-potties were frozen solid, and the company, complaining that their maintenance equipment has become useless, were pulling the toilets out for the winter. Compostable toilets, being built for the winter, were not ready yet. Every piece of skin exposed to the wind froze. We were melting ice with propane gas for dishwater.

In the kitchen, ice flakes fell with every gust of wind, and I worked with frozen eggs, chicken, and cans to prepare hot meals. We served around a hundred people with the donated food and carried leftovers to the nearby medic tent.

-Victory for the Struggle, or a New Beginning?

On December 8th, Sioux Tribe chairman David Archambault II declared Oceti Sakowin closed to newcomers and asked everyone to evacuate. It was a decision based on the ever worsening weather, road conditions, and the safety of the Water Protectors.

Bill Hill’s Bus also left in a hurry. Some people stayed or sought shelter at the casino on the reservation. The casino was filled with people to the hallways, and conference rooms were filled with Water Protectors in sleeping bags.

The next storm was going to drop temperatures to below -30C ( -22F), and the winds made any new construction efforts difficult. Even while we were leaving the camp, we passed by dozens of cars stuck in ditches and snowdrifts on both sides of the road.

The bus engine took several hours of melting with a propane heater before it started again. The bus had been used for a week as a shelter for a dozen people and was filled with sleeping bags, comforters, pads, and backpacks, as well as a wood stove and firewood. We cleaned up as much as possible and left as soon as possible, but with a bitter aftertaste.

-The Way Home

The Bus made about 100 kilometers (60miles) before breaking down with a brake failure. We limped over to a car shop in a small town in South Dakota and camped for the night. At midnight I woke up to a man banging on the bus door.

“What are you doing in a pro-pipeline town?” He asked us. “You aren’t getting any help around here, you should leave in the morning,” he said before leaving. In the morning, to nobody’s surprise, the mechanic was “too busy” to help us, and we towed the bus to the next, larger, town.

Bill never got the bus fixed completely, and had to park it at Bill’s friend’s garage in Iowa. The crew got on a rental minivan and drove through another snowstorm before arrival in New York on the 12th.

Hi.

I remember when you told me in the past.

Please connect me later.

My English grammar is sommething like a baby. Hoho please understand.

Nice to meet you and I hope your health.

Please give a call later. Bye my Friend.

See you soon.