The politics of art in the art of politics: South Korean art festival marred by censorship scandal

By Joel Lee

A South Korean art exhibition is embroiled in a storm of international controversy after an art work was pulled under political pressure, raising the issue of freedom of expression and censorship.

The Gwangju Biennale, an art festival dedicated to the spirit of democracy, is held in the host city of Gwangju from Sept 5 to Nov 11 celebrating its 20th anniversary, albeit under undemocratic circumstances leading to its opening.

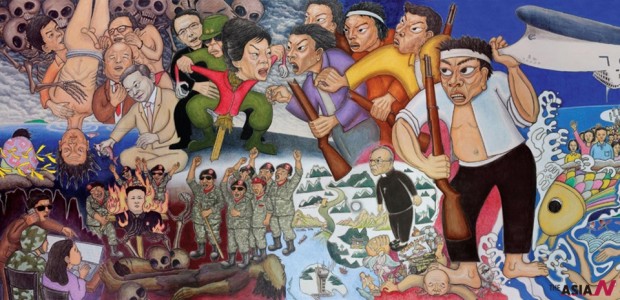

The center of the withering criticisms, both at home and abroad, is a painting by artist Hong Seong-dam entitled, “Sewol Owol,” which the defiant painter dedicated to the 300 perished lives from the mid-April ferry disaster, mostly of high school students. One of the students worked at Hong’s studio part-time and dreamed of becoming a painter.

Hong’s ten-meter-wide mural has become an object of scorn for many as it depicts figures in a phantasmagoria of satirical images. On the top left side, a caricature of South Korean President Park Geun-hye is portrayed as a scarecrow controlled by her late father, former president Park Chung-hee who ruled the country for nearly two decades with an iron fist. Sinister figures lurk behind, alluding to the powerful corporate and bureaucratic forces which many see as puppeteering Park’s government.

“Owol” means month May in Korea, also symbolic of the 5.18 Gwangju Democracy Movement of 1980 in which the former military regime under Gen. Chun Doo-hwan massacred and tortured hundreds of civilians.

“What they did (forcing me to withdraw from the event) was proof of what I tried to say in the painting. Under Park Geun-hye, the country is reverting to the old practices of her father’s era, repressing the freedom of expression,” Hong said in The New York Times article, “An artist is rebuked for casting South Korea’s leader in an unflattering light.”

Park’s administration has faced a spate of scathing charges for botching the rescue operation and investigation into the ferry accident. Critics point out lax safety regulation put under the previous Lee Myung-bak administration – and handed down to Park – as one of the root causes sinking the ill-fated ship.

The painting, originally scheduled to cover the façade of the Gwangju Museum of Art, was denied entry just before the opening for its “explicit political intention.” Opposition led by the city major – a 35-year friend who fought together with Hong in the 1980 Gwangju movement and introduced Hong his wife – cited its threat to the “republican prestige” as so often touted by Korean conservative pundits.

Gwangju’s “authoritarian turn” was unexpected given its official commitment to being Asia’s central city of culture. Under Korea’s highly centralized bureaucracy, the city government is at the mercy of the state in receiving public funding. With the city officials head over heels in trying to secure a $3 billion cultural project by 2015, they are in no position to tick off their main financial sponsor.

“Gwangju may seem like a liberal city from outside. But if you look inside, it is very conservative. This incident got enmashed in trying to solve problems not by principle, but by politics,” Park Ho-jae, an official at Gwangju Cultural Foundation told investigative magazine SisaIn.

The Art of Resistance

Across international art circles and media, opinions are critical. Aside from Korean media, The New York Times, Artnet News, SINA News and DiePresse reported on the censorship fiasco along with The Wall Street Journal.

“I don’t think it is taboo to satirize a country’s president. Freedom of expression should not be restricted by the government just because they have the exhibition budget ($2.4 million) under their control,” resigned President of Gwangju Biennale Foundation Lee Yong-woo said in a press conference in mid-Aug.

Yun Beom-mo, the designated curator who also resigned, echoed Lee’s view, saying, “The decision not to exhibit Sewol Owol was made in the absence of the chief of curator. Guaranteeing artists’ freedom of expression and the ‘Gwangju spirit’ cannot be separated.”

Artist Lee Yun-yop who boycotted the event added, “I thought it wouldn’t be good for an artist to simply do nothing. If they won’t put up Hong’s work, does it make our works ‘appropriate’ past the censors?”

Across the sea, Japanese artists joined the league by vowing to withdraw from the event. The director of Sakima Art Museum in Okinawa, which was to lend an art piece by German artist Kathe Kollwitz famous for anti-war theme, wrote an open letter to the foundation to “display Hong’s painting and respect the purpose of the exhibition.” “Otherwise we don’t see a reason to participate in an exhibition losing its founding purpose,” it added.

Healing the wounded by the wounded

The original theme of the festival, “Sweet Dew – 1980 and After,” has changed to “Burning Down the House.” A giant green octopus, engulfed in an opaque smoke, fills the façade, representing the “creative destruction” the venue purports to be.

Had “Sewol Owol” been part of the exhibit, visitors might have witnessed a scene of the “inconvenient truth.”

“This painting is about the pain of Korea’s contemporary history, the irony of a wounded person healing another wounded person,” Hong told the SisaIn magazine. “That there is no critic who can read the sadness of the painting saddens me,” he added.

Art critic Kim Jong-gil said: “It is an art work showing reality, unreality and surreality. It is a shamanistic work bringing back timeless memories. The ‘May spirit’ is about searching a new problem of our time. For Hong, today’s May is Sewol. For us, Sewol is an event demanding a paradigmatic turn. We ask, what happiness is, what we should live for, through this painting.”