Is North Korea a ‘communist state’ or a ‘market economy’?

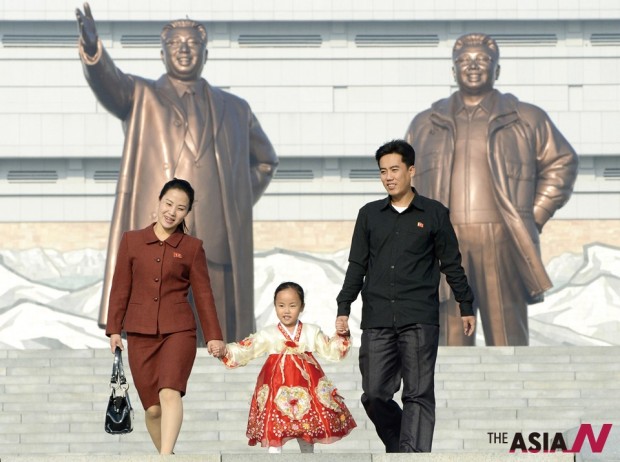

A North Korean family visits the statues of late leaders, Kim Il Sung, left, and Kim Jong Il on Mansudae to mark the 68th anniversary of the founding of the ruling Workers' Party of Korea, in Pyongyang, Oct. 10, 2013. (AP/NEWSis)

North Korea is often described as a ‘communist country’ by outsiders, and also officially describes itself as a ‘socialist country.’ But, what exactly is a ‘communist state,’ or (to use a less ideologically charged term) a ‘country of state socialism’?

It is usually a country where all or most of its industry is in state hands, and almost all arable land is managed by the state as well. If we apply this definition, though, North Korea of the 2010s is by no means a state socialist country. It is true that once upon a time it used to be a near perfect specimen of Leninist state socialism, but this time is long gone.

The halt of Soviet and Chinese economic aid in the early 1990s triggered a dramatic economic crisis. The industrial output halved and agricultural production fell below subsistence levels. A disastrous famine killed about a half million people. Amidst the destruction, though, a new North Korean economy was born. This economy was essentially capitalist – but to avoid ideologically dangerous terminology, it might be better to call it a ‘market economy.’

In the mid-1990s, North Koreans rediscovered markets and reestablished private enterprises. They began to toil in illegal and semi-legal private plots. They stole and sold the equipment and produce of the factories they worked at, they traded all kinds of items, they provided services, and they began to manufacture simple things in their own in-house workshops.

The growth of markets profoundly affected society, replacing old inequalities with new ones. A class of nouveaux riches appeared. Some of these people struck riches thanks to their official connections, while others started at the bottom of the old hierarchy and rose to the top of the new pyramid through a combination of luck, ruthlessness and hard work.

The new rich class

By the early 2000s, some of these new rich – known in North Korean parlance as tonju or ‘masters of money’ – had amassed rather significant fortunes. Some of them had fortunes amounting to many tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is serious money in a country where official salaries have fluctuated around $1~2 a month, and where actual incomes are probably as low as $15~20 per month per capita.

The growing capital of these rich had to be invested somewhere, but the scale of most private enterprises was small, which was only natural because most of the above mentioned economic activities remained technically illegal in North Korea. North Korea’s grass roots capitalism also lacked the necessary infrastructure that would allow it to grow above the level of small family-based ventures.

In the early 2000s (or perhaps slightly earlier), the ‘masters of money’ discovered a new investment vehicle: they began to invest in what were ostensibly state enterprises. Initially they used state enterprises as a legal shell, a convenient signboard that would allow them to operate relatively large businesses.

It seems that one of the first areas where pseudo-state enterprises became common was the restaurant industry. Starting from the late 1990s it became common for private investors to make deals with municipal governments, bribing local officials in order to get permission to use a non-operational or almost non-operational state restaurant. Investors would hire skilled personnel, buy the necessary equipment and arrange for the restaurants’ interior design. Then perhaps investor-appointed managers would be entrusted with the daily operation of such enterprises.

Officially, such operations are considered to be state enterprises, humble subsidiaries of municipal governments. But in actuality, they are private in all but name. The owner is supposed to transfer a certain portion of revenues to the state budget, as if it were the profit of a good old ‘socialist enterprise.’ On top of this, local officials have to be provided with regular kick-backs, just to ensure that they will leave the business alone. It has been recently estimated by Yang Munsu (a prominent and highly respected economist dealing with North Korea) that some two-thirds of North Korea’s restaurants are run in this way. The present author suspects these may even be underestimates. The actual figure might be close to 90 per cent.

A North Korean traffic policeman carries out his duties on July 22, 2013 in Kaesong, North Korea. (AP/NEWSis)

In this regard, Ms. S has a fairly typical story. In the early 2000s, Ms. S made good money by doing private trade with China (where her husband’s relatives resided). Around 2004, she had tens of thousands of dollars to her name, and she decided to open a restaurant, while continuing her highly profitable garment business. She made a deal with local authorities and got control of a large, non-functioning restaurant near the market of her native town. Being too busy with her major business, she hired her close school friend to be the restaurant manager. The restaurant operated for five years. Apart from the city government, Ms. S had to pay the local police, the local secret police, the local party committee, and local health inspectors. Apart from monetary rewards, the officials from these highly esteemed agencies were entitled to feast at her restaurant, any time, free of charge.

Ms. S admits that her restaurant was moderately profitable, but she eventually decided to shut it down, because it attracted unfavorable attention to herself and was at times rather troublesome to manage.

Mr. K was luckier. Because of a few unusually successful years in the restaurant business, he was able to earn enough money to move into a far more serious business – he acquired a small gold mine. Officially, the gold mine was owned by the foreign currency earning branch of the party Central committee, but for all intents and purposes, Mr. K and his brother were the owners. They bought equipment from non-functioning state mines, hired workers, and managed to produce enough gold to have a net income of roughly $2,000 a month.

Whose restaurant is it?

Another area where pseudo-state enterprises abound is transportation. The growth of the private economy and trade would have been impossible without the ability to move people and cargo across the country.

Entrepreneurial people began to buy used trucks in China and bring these rusty contraptions (still impressively modern by North Korean standards) across the border. They registered these tracks with North Korean state agencies, but the trucks were owned and operated privately.

The relevant agencies therefore did not get any use of the vehicle, though the relevant bureaucrats received regular payments for their willingness to lend the agency’s good name to truck owners. Interestingly enough, the kick-back’s size is dependent on the importance of the agency; registration with a military unit is far more expensive than registration with a humble third-rate factory.

In recent years, it seems that the line between state and private production has become even more blurred. Operators of state enterprises have begun to look for private investment and of course have found ways to reward investors for their willingness to cooperate.

An old Korean hand, a frequent and long-term foreign resident of Pyongyang, recently described the situation to the present author, “it is quite complicated now, you go to a restaurant, and this restaurant is technically owned by the foreign currency earning department of say state security. But somewhere in the state security bureaucracy there are also a couple of racketeering generals who personally ‘take care’ of the restaurant, and there are also a couple of real investors whose private money is used to run the restaurant. God only knows who the actual owner is, but the food is great and the service is fantastic, especially if you remember how it used to look like in Kim Il Sung’s days.”

Pingback: What is marketization and when did it begin in North Korea?