Genocides in Modern History

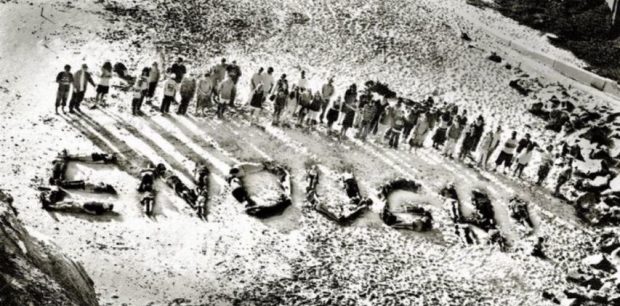

Save Darfur activists from Orange County (Genocide Intervention Network)

By Mayy ElHayawi,

Associate Professor of Literary Studies, Egypt

CAIRO: No matter how accurate the calculation of the death toll or causalities is, the number of those traumatized by the genocidal memories of killing, burning, torture, burial, rape or escape would always remain a mystery – seemingly revealed in testimonies, narratives, memorials or recollection rituals, yet intrinsically concealed in distressed consciousness, misinterpreted by troubled consciences or obscured by post-traumatic amnesia.

Undergoing or witnessing brutal physical violations not only scars survivors’ bodies and psyches, but also encapsulates them in a loop of death wherein oblivion is an unattainable luxury and survival is an unforgiven guilt.

Hence, rather than investigating the accuracy of the statistics that report the killing of almost half a million and the displacement of three million human beings since the start of the conflict in Darfur in 2003, this article (which will be published in a serialized format) will focus on how the lifelong catastrophic impacts of the first genocide in the 21st century are retained and articulated through subjectively perceived, yet collectively enforced and/or endured bodily experiences.

It will also highlight how enacting embodied memories can be the means for scrubbing personal and collective wounds, redeeming distorted identities, reconstructing the disrupted self and sewing it back into the social fabric of the present.

Bodies and memories are the key players in the victimizers’ perpetuation of a genocide and victims’ resistance of genocidal atrocities.

Mayy ElHayawi

While the former’s allegations of racial, historical, or religious supremacy justify the annihilation of those different in color, ideology or heritage, the latter’s embodied memories of physical and psychological suffering fuel the struggle to reveal the brutalities, commemorate the sufferers and bring criminals to justice.

The term ‘genocide’ itself – a combination of the Greek word ‘genos’ (race or tribe) and the Latin root ‘cide’ (killing) (Lemkin) – was coined in 1944 by the Polish‐Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin (1900–59) who was appalled at the “sinister panorama of destruction of the Armenians” and eventually traumatized by the Nazi invasion of his homeland and the extermination of his family in the Holocaust gas chambers (Lemkin and Freize).

Lemkin’s lifelong struggle – to internationally outlaw “the destruction of peoples” and protect not only “the physical bodies” but also “the collective minds of nations“– was nurtured by what he called: “a mixture of the blood and tears of eight million innocent people throughout the world” including his parents and friends (Lemkin and Freize).

It is true that Lemkin finally managed to get the United Nations to ratify the “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” in 1951, in which genocide, as defined hereafter, was condemned as a “crime against international law”:

Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Unfortunately, the blood and tears shed during the first half of the 20th century were only enough for acknowledging and outlawing genocides, but far too inconsiderable to prevent them.

In the “age of genocide,” as Roger W. Smith maintains, “60 million men, women, and children, coming from many different races, religions, ethnic groups, nationalities, and social classes, and living in many different countries, on most of the continents of the earth, have had their lives taken because the state thought this desirable”.

Jews and Armenians were only a part of a long list of victims that included: “Cambodians, Bosnians, and Rwandan Tutsis, …Ukrainian peasants, Gypsies, Bengalis, Burundi Hutus, the Aché of Paraguay, Guatemalan Mayans, and the Ogoni of Nigeria” (Hinton).

Mayy at a Stanford University Guest Lecture (Linkedin)

The huge diversity of victims as crystalized in the aforementioned list – “Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, Muslims; Communists, non-Communists; kulaks, intellectuals, workers, stone age hunters, national groups, homeless peoples; persons who are black, brown, red, yellow, white,” and the shocking array of mass-killing pretexts – “race, religion, ethnicity, physical condition, political opinions, class origins, or stage of historical development” (Smith), have rendered every human being vulnerable to a similar fate.

Bewilderment, anger, curiosity and fear fueled the dramatic rise of academic genocide studies in the last decade of the 20th century, which is manifested in “the emergence of new scholarly journals since the 1990s,” the publication of “Encyclopedias of genocide” (Bloxham and Moses), and the proliferation of analytical, descriptive, diagnostic, comparative and pre-emptive research focusing on reports, statistics, testimonies, resolutions, laws, case studies, media, memorials, school curricula, narratives and works of art.

Nevertheless, none of the above could ghost-proof the third millennium or save humanity from the genocide demons growing out of perpetrators’ viciousness and witnesses’ indifference.