NATO recommendations should be used to save lives

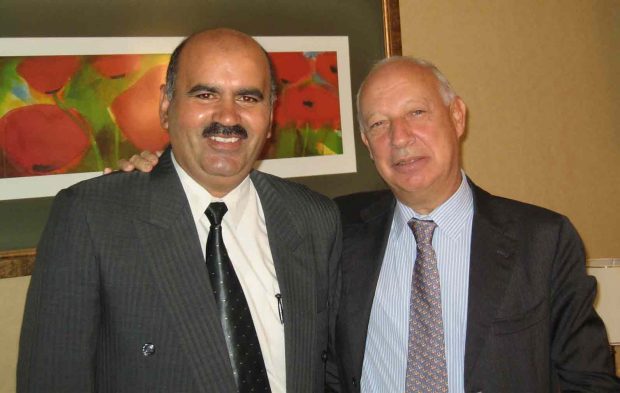

With Anders Fogh Rasmussen NATO Secretary General (2009 – 2014) and Nicola de Santis

By Habib Toumi

BAHRAIN: Going through the recent assessment of NATO’s engagement in Afghanistan and the ensuing recommendations, I had an eerie feeling of déjà-vu.

One recommendation read: “When planning and conducting future operations, Allies should continuously assess strategic interests, remain acutely aware of the dangers of mission expansion, and seek to avoid taking on commitments that go well beyond assigned tasks. NATO should establish realistic and achievable goals and seek increased participation by other international actors who are better suited to deliver those non-military effects.”

Another recommended that “future NATO train, advise and assist missions should carefully consider the political and cultural norms of the host nation and the ability of that society to absorb capacity building and training.”

The recommendations were included in a comprehensive assessment launched by NATO about its engagement in Afghanistan.

The Afghanistan lessons learned process “included both operational-military and political reviews, each covering the full timeline of NATO’s involvement, from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and the invocation of Article 5 of the Washington Treaty, to the evacuation from Kabul in August 2021.”

I have been a member of a group of journalists from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) who had the chance to become familiar with the situation on the ground in Afghanistan and the open opportunities and formidable challenges and there.

Thanks to NATO’s Public Diplomacy Division and the driving force within it, the flamboyant Nicola de Santis whose insightful analyses, genuine thoughtfulness and Mediterranean sense of priority (Take life seriously, but with a joyful attitude). made him a favorite among MENA journalists, we had gained great insights into what was happening Afghanistan.

We were from countries that were members of the Mediterranean Dialogue or the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative, the NATO cooperation partners in responding to the new challenges of the 21st century.

We had ample opportunities to talk freely with, and to challenge openly, NATO policy makers, decision makers, field experts, and analysts as they shared a wide spectrum of sharp views, strong comments and deep insights.

Thanks to the Public Diplomacy Division, we listened to Hamid Karzai (President of Afghanistan, 2001-2014) and conversed privately with Ashraf Ghani (President of Afghanistan, 2014-2021), Afghan lawmakers and diplomats from the region. We came to appreciate both the Afghan, regional and international dynamics of the dramatic events unfolding in Afghanistan. We learned about the issues, challenges and opportunities in Afghanistan and for Afghans, NATO and other actors.

I remember a conversation my friends Khalid and Hafedh and I had with an Afghan lawmaker in Chicago in May 2012.

“What is happening to your army? Why do so many recruits get outstanding NATO training but later switch sides?”, we ask.

“They are contacted by the other sides who offer more money and promises of better family security,” she explained.

When Afghan recruits became afraid that there would be no death benefits for their families if they were killed, or when they were not given SIM cards to call their families, they felt let down, deserted and switched sides.

With NATO (former) Deputy Secretary General Alessandro Minuto Rizzo

My dear friend Alessandro Minuto Rizzo, the former deputy secretary general of NATO and today president of the NATO defense college foundation, later confirmed her statement in comments on how NATO left as a fighting force and launched the Resolute Support Mission (RSM) to train, advise and assist Afghan security forces and institutions to fight terrorism and secure their country.

“During the training, the mistake was to believe that the Afghan military would obey the flag, when instead they obey first to the clans, to the family …,” he said.

To us, Afghanistan (and Iraq) were not afterthoughts and we recognized that we were much more fortunate than colleagues and the public in other countries.

“Out of a combined 14,000-plus minutes of the national evening news broadcast on CBS, ABC, and NBC in 2020, a total of five (05) minutes were devoted to Afghanistan. In the preceding five years, the average was only 24 minutes per network per year.” (Andrew Tyndall, the editor of the Tyndall Report).

We became aware that, unfortunately, too many layers in the intricate relations between the political and military spheres have caused confusions and tragedies, decisions hurt the ability to succeed, situations on the ground were misrepresented, achievable objectives were not defined realistically…

We were not shocked by what happened in Kabul in August. It was tragic and deplorable. Yet, it had been expected. I here refer again to Minuto Rizzo.

“It was thought that once a government was created, there would be a parliament, elections, that the country would organize itself. But Afghanistan is a very particular country; it has no access to the sea, it is difficult to access, with a substantially tribal history, in Kabul there was a king who reigned, but in the provinces everyone did what he wanted, there is a majority Pashtuns and there are many minorities, the Tajiks, the Uzbeks, the Hazaras … building a national government is a complex thing that takes a long time and we in the West are no longer used to it,” he said.

No matter how many articles, features, analyses and books will be written about what happened in Afghanistan and why it happened, there will always be plenty of room on the shelves for more. Many more.

Now that NATO has conducted a comprehensive assessment of its engagement in Afghanistan and published its recommendations, ensuring their full application should be a major goal.

This means building the recommendations into a binding “constitution” for dealing with regions and countries.

It is an acid test with heavy consequences. With its “historical, political, operational and cultural expertise, realistic and achievable goals and increased participation by other international actors who are better suited to deliver non-military effects”, NATO could make sure that “thousands do not lose their lives, and that many others do not suffer visible and invisible wounds.”