Run-ins with Lee Kuan Yew cut short young activist’s career

Arun Mahadeva

By Ivan Lim

Former AJA President, Contributor to AsiaN

SINGAPORE: On Sept. 27, 1957, a bright 26-year-old activist, Arun Mahadeva, Maha for short, was invited to meet Lee Kuan Yew,34, a United Kingdom-trained lawyer and up-and-coming politician who was soon to become Singapore’s Prime Minister.

At the meeting in Lee’s law office, the secretary general of the People’s Action Party offered the soon-to- graduate youngster an important job. This was to head a research unit the PAP was planning to set up in Lee’s coming battle with left-wing rivals for trade union supremacy.

Not only that, the solicitous Lee also held up the prospect of fielding the activist in the general election in 1959.

The meeting broke up with Maha having no job and getting into Lee’s list of opponents.

According to a new book on events that followed, Maha as a journalist and unionist was treated by Lee as a foe as the PAP and the Barisan Sosialis fought it out in the early1960s to gain power from the departing British authorities.

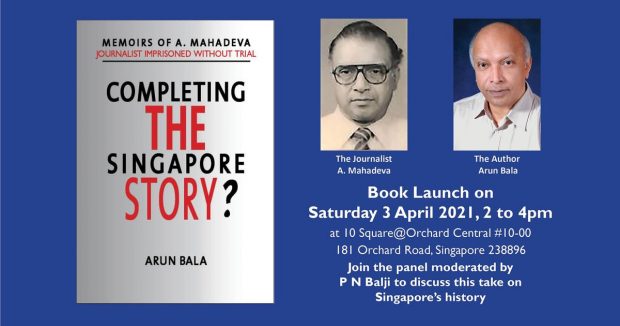

Titled “Completing the Singapore Story? Memoirs of A. Mahadeva –Journalist Imprisoned Without Trial”, the book shed light on Lee’s scant tolerance for independent political journalism, as seen in the way he dealt with the newsman. The book is the latest in a series of writings offering a counter-narrative to the “The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew”, published in 1998.

In 1957, upon his graduation from the University of Malaya (a merger of King Edward VII College of Medicine and Raffles College set up by the British in Singapore), Maha joined the Singapore Tiger Standard and was quickly thrust into the hurly burly of the fast-changing politics of day.

Then, as a reporter in The Straits Times, he had occasional run-ins with Prime Minister Lee, which left him wary of the politician. In turn, their encounters and exchanges led Lee to view Maha a partisan journalists aligned with Lim Chin Siong and his left-wing cause.

As recounted in the memoirs, a dramatic exchange took place in 1959 during a general elections rally outside the Nanyang Shoe factory in Bukit Timah.

On spotting Maha there, the PAPleader shouted out: “What story are you writing about? You don’t even name the person who received money from the CIA to help defeatg the PAP.’’ He was referring to one Chew Swee Kee, whose identity had not yet been disclosed publicly.

Maha retorted that he was doing his duty as a reporter, writing about what he had learned through his investigations. If Lee was prepared to name names, then, as a professional, Maha would report it.

But Lee apparently found it politically inconvenient to do so. And Maha would not go against his journalistic principles to help the PAP, sympathetic though he was, at that point, to the party’s democratic socialist platform.

While an undergraduate, he had joined the University of Malaya Socialist Club and embraced the democratic socialist cause espoused by the local elites fired up by nationalist feelings through post-War Asia, and taking up the charge to oust British in Singapore. Among the activists he befriended were Sandra Woodhull, S.T. Bani and Dominic Puthucheary, who later headed trade unions involved in mobilising workers in the anti-colonial struggle. Maha was circulation manager for the Socialist Club’s organ, the Fajar, which figured in a high-profile sedition case in 1954 brought against it by the colonial government for its editorial, “Aggression in Asia”.

Maha also got to know closely Jamit Singh, the fire-brand chief of the left-wing Singapore Harbour Board Staff Association, and an early supporter of Lee Kuan Yew, who was elected in the port constituency of Tanjong Pagar.

Maha had done a study of the salary structure of Asian port workers for his final-year university thesis – which could explain Lee’s earlier offer to Maha of a labour research post.

Through these contacts, Maha was to get to know union leader Lim Chin Siong, who was calling the shots in the anti-colonial movement of largely Chinese-educated rank-and-file in the private sector. Lim was regarded as the man who would be Prime Minister of an independent Singapore.

Meanwhile, a group of ‘returned students’ with lawyer Lee Kuan Yew, economist Goh KengSwee and scientist Toh Chin Chye as its core, and agitating for de-colonisation in the Malayan Forum in London, began to tap into the Chinese mass movement.

Lee and Lim joined hands in forming the PAP to contest the British-sanctioned elections leading to self-government. Maha threw himself into the electioneering campaigns that sawthe PAP triumph over the pro-establishment conservative Progressive Party. Lee became Prime Minister of a self-governing Singapore in 1959.

But in 1961 there was a split in the PAP leadership over terms for joining the proposed Federation of Malaysia endorsed by the British to protect their interest in South-East Asia. Lim Chin Siong’s faction left to form the Barisan Socialis. The issue of merger with the federation of Malaya was put up for a national referendum.

Maha, who had become the founder secretary general of the Singapore National Union of Journalists (SNUJ) on 12 February 1961, protested against the PAP’s merger proposals that asked voters to tick three boxes all in favour of merge but without any provision for a say against it.

To rebut charges that SNUJ was playing party politics, Maha said the union was merely objecting to the undemocratic feature of the Bill in denying the voters the right to choose.

However, Lee saw it as politically partisan act by Maha in siding with Lim Chin Siong, who also opposed the PAP formulated Bill.

In a tactical move, the Barisan Socialis urged voters to reject the Bill by casting blank ballots but the PAP quickly amended the law to count blank ballots as “yes” votes for merger. On 1 September 1963, the lot was cast and up to 70 per cent voted “yes” for merger. Singapore joined the Federation of Malaysia on 16 September, the birthday of Lee Kuan Yew.

Whether he foresaw the coming storm, Maha was soon to pay a heavy price for exercising his right to comment and come out with criticisms.

On February 2, 1 963, he was nabbed during a security sweep that targeted over 100 left-wing activists such as Lim Chin Siong and his BarisanSosialis comrades

They were detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance (now Internal Security Act). The sweep, codenamed Operation Coldstore by the Internal Security Council, was launched by the British, Singapore and Malaya authorities to cripple the activities of the communist united front organisations that purportedly posed a threat to Singapore’s internal security.

Maha’s incarceration was to cut short the 31-year-old activist’s media and union career to which he would not be able to return. The Singapore authorities saw to it that he would not be allowed to work as a journalist again even when the Straits Times was willing to take him back.

On October 29, 1968, the forgotten detainee was freed after appearing on TV to read out a Special Branch- scripted confession of his past ‘pro-communist” activities.

According to the Straits Times report, “former journalist and left-wing trade unionist Arunasalam Mahadeva was released from political detention today after a public disavowal of his pro-communist activities six years ago.”

But did he recant his deeply-held political beliefs? No. The posthumous biography A. Mahadeva sheds new light on Maha’s quandary.

“As a journalist, he was more in tune with the so-called Bandung stance of staying neutral in the on-going conflict between the Western powers and the Soviet Union. This position, favoured by Lim Chin Siong and his party, was at variance with the pragmatism of Lee and his group of working with the British to achieve smooth transition to independence for Singapore.”

Mahadeva passed away in 2005 at age 74. His posthumous biography by his scholar- brother, Dr Arun Bala, itself a labour of love, vindicated Maha as an independent-minded principled journalist and trade unionist who hewed to the democratic socialist, non-communist, path.

It is a pitfall of journalism that his writings were seized upon by Lee Kuan Yew as politically aligned with the charismatic Lim Chin Siong, who could have been the Prime Minister of Singapore.