Xi Jinping’s Subtle Summitry on the Korean Peninsula

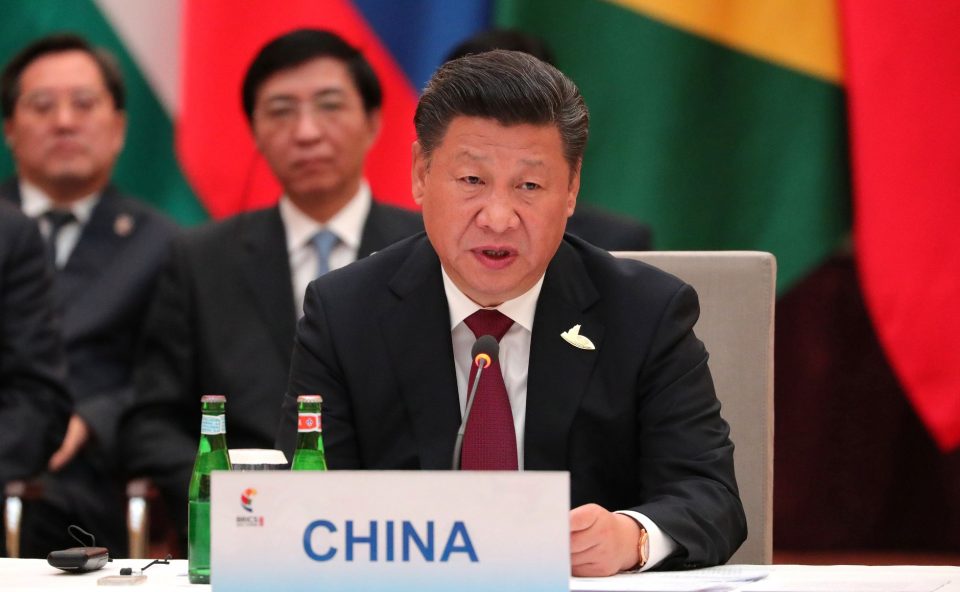

As a pragmatist, Chinese President Xi Jinping patiently and methodically chooses the means and procedures to achieve his “China Dream,” waiting until China is ready and able to revise the global strategic, economic and diplomatic order led by the United States. His efforts to balance revisionist goals and pragmatic means are evident on the Korean Peninsula, where China’s core national interests are at stake. Indeed, he once told US President Donald Trump that Korea had been part of China. This view is amply illustrated by Xi’s recent series of summit meetings with respect to the peninsula. Xi takes full advantage of the opportunities presented by summits and seeks to exercise influence over them. Yet he is careful not to assume direct responsibility and bear the full costs associated with the outcomes of such meetings. Hence, his summit diplomacy demonstrates both the promise and the limitations of China’s international pursuits.

Anger on Display: China and South Korea

After having experienced a roller-coaster relationship with former South Korean President Park Geun-hye, Xi expected that President Moon Jae-in, a progressive reformer and nationalist, would lessen South Korea’s dependence on the US and improve strained relations between Beijing and Seoul. He also hoped that the two governments would be able to co-ordinate their respective policies toward North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. At the time of his inauguration, Moon dispatched a high-level delegation to meet with Xi. Disappointed by what the Chinese regarded as Moon’s capitulation to US pressure by keeping in place the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile installations, he apparently intended to use summit diplomacy to teach Moon a lesson about challenging China’s national security interests. At their summit meeting in Beijing in December 2017, Xi candidly told Moon that there was a “retreat” in their relations due to the THAAD dispute, but he hoped that the summit meeting would present an important opportunity to improve bilateral relations on the basis of “mutual respect and trust.” He expressed his willingness to “normalize” the economic and cultural relations that the THAAD controversy had significantly undermined. Moon presumably assured Xi that the THAAD system was not directed toward China’s military installations and that South Korea would not expand the system any further. Once North Korea’s nuclear and missile issues were resolved, Moon assured Xi, the THAAD batteries would be removed once and for all.

The two leaders agreed on four principles — to oppose war on the Korean Peninsula; to support the goal of North Korea’s denuclearization; to settle North Korea’s nuclear and missile issues peacefully through dialogue and compromise; and to recognize that an improvement in inter-Korean relations would be conducive to the peaceful resolution of the Korean questions. Alarmed by Trump’s increasingly militant rhetoric about “fire and fury” and “little rocket man,” this agreement was intended to counter a possible use of force against North Korea by the US. Xi also advanced a “dual-freeze” initiative: North Korea would freeze its nuclear and missile tests in exchange for the US and South Korea suspending their joint military exercises, which the Chinese feared could also threaten China’s national security interests. It was widely reported in the South Korean media that Xi deliberately mistreated or even snubbed Moon both in terms of protocol and substance. Moon was discreet and did not reveal his inner feelings, putting a positive spin on his meeting with Xi. It is not difficult to imagine that Moon indeed learned a lesson not to underestimate the implications of China’s rude behavior. But if it was Xi’s intention to drive a wedge between Washington and Seoul, his summit diplomacy was less than successful. While Moon’s domestic opponents were quick to criticize his diplomatic ineptitude as well as Xi’s insults, public opinion in South Korea turned against Xi for what was viewed as a display of big-nation chauvinism and strong-arm tactics.

Despite Xi’s promise of economic normalization, the Lotte Corporation’s operations in China are still not back to normal, because Lotte had provided a site for the THAAD deployment. Nor has China fully removed restrictions on South Korean business activities in China. In the subsequent unfolding of diplomatic activities regarding the Korean Peninsula, however, Moon has no choice but to cultivate close consultations with China and to exchange high-level emissaries between Beijing and Seoul. It will take some time before China and South Korea can restore mutual trust and carry out a “strategic co-operative partnership.” When Xi visits Seoul, his second summit meeting with Moon is likely to be more productive than the first one.

Leverage and Advice: China and North Korea

As soon as Kim Jong Un indicated his willingness to meet with Moon and Trump, Xi invited Kim to China three times in the span of less than three months in 2018. This unprecedented summit diplomacy represented Xi’s desire to assert China’s important role in managing Korean affairs. In March 2018, on his first foreign visit as North Korea’s supreme leader, Kim received the red-carpet treatment from Xi amid great fanfare. It stood in sharp contrast to the cool reception extended to Moon only three months before. Xi fully embraced Kim’s rule as legitimate and praised his courage for seeking new diplomatic horizons. Evidently, Xi gave specific recommendations for Kim’s forthcoming negotiations with Moon and Trump. It was particularly notable that Kim and his entourage were excessively deferential to Xi, as if they accepted a patron-client relationship with China. Viewed from Kim’s perspective, the summit with Xi overcame a sense of diplomatic isolation and enhanced his standing in the eyes of North Koreans. He also strengthened his hand at the negotiating tables with Moon and Trump. Most importantly, Kim hoped to loosen, if not nullify, China’s public adherence to the UN-mandated sanctions that severely constrained North Korea’s economic life. Emphasis on the lasting importance of the traditional friendship between China and North Korea was reiterated. It is likely that Xi made sure that Kim should not undermine China’s fundamental interests in his meetings with Moon and Trump. Given that Kim had unilaterally announced his decision to freeze nuclear and missile tests, Xi presumably emphasized that Kim should make every effort to obtain Moon’s or Trump’s commitment to freeze US-South Korea joint military exercises.

Ten days after his first summit meeting with Moon at Panmunjom, Kim accepted Xi’s invitation for a second talk in Dalian. Xi complimented Kim for “promoting inter-Korean dialogue and easing tension” on the Korean Peninsula. It is likely that Kim briefed Xi on aspects of the Panmunjom Declaration, including what was meant by “complete denuclearization” of the peninsula and why North Korea was eager to obtain a declaration to end the Korean War. It is not clear whether Xi wanted China’s direct participation in this declaration with the US, North Korea and South Korea. Asked about this question toward the end of May 2018, a high-ranking South Korean leader said that China took a passive and noncommittal attitude toward the question of a joint declaration. However, China is expected to play an active role in the negotiations for a peace treaty on Korea. A week after the historic Trump-Kim summit meeting in Singapore, Xi invited Kim yet again to Beijing. Following their summit meeting, Chinese spokesman Geng Shuang said that the two leaders deepened bilateral relations, strengthened “strategic communications,” and agreed to co-operate for regional peace and stability. Among other things, Xi was particularly pleased with Trump’s announcement to suspend what he called the provocative “war games” — namely, US-South Korea joint military exercises. Xi’s “dual-freeze” initiative was thus realized. It is most likely that the two leaders discussed what steps should be taken to implement complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula and how they would co-ordinate their respective approaches toward the unpredictable Trump. It is also likely they discussed how China, along with Russia, might ease or remove the economic sanctions on North Korea at the United Nations Security Council and how much economic assistance Beijing could eventually give to Pyongyang.

Even though the Chinese have consistently urged both North Korea and the US to conduct an inter-governmental dialogue and to normalize their diplomatic relations, Xi may be concerned that just as his grandfather did so well in the context of Sino-Soviet conflicts, Kim Jong Un might be tempted to adopt a balance of power policy between China and the US or might even tilt toward the US in a package deal over nuclear and missile issues. Aware that Kim was thoroughly educated in his grandfather’s Juche (self-reliant) ideology, Xi may feel that he should handle the young and sensitive Kim with tender care. According to a long-time resident in Pyongyang, China is more unpopular than Japan and America among ordinary North Koreans, primarily because China, with its great wealth, is rather miserly in assisting North Korea. Moreover, they feel betrayed by China’s decision to vote for the sanctions resolutions on North Korea at the UN Security Council. The well-publicized Xi-Kim summit meetings may have considerably soothed the ill feelings in North Korea. And Xi’s anticipated fourth summit meeting with Kim in Pyongyang is expected to further solidify China-North Korea co-operation. Neither Xi nor Kim shows any desire to abrogate or revise the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance signed by the two countries in 1961. They probably prefer to preserve the treaty (especially Article Two on mutual defense) as a deterrent against the US and South Korea and as a bargaining chip at future negotiations for a peace treaty on Korea.

One key question that remains is whether Kim Jong Un will faithfully carry out his promise for complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. Moon is confident that Kim will do so if economic sanctions are lifted and security assurances are provided for North Korea. Unlike Moon, a number of prominent Chinese scholars — such as Professors Wang Jisi and Zhu Feng — who are known to be influential with Xi, openly express skepticism about Kim’s commitment. If Kim Jong Un reneges on the promises made at Panmunjom and Singapore, what can Xi do? In view of China’s realistic calculations, it is doubtful that Xi would mobilize all his leverage to compel Kim’s complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization. For pragmatic reasons, Xi may opt for a policy of nuclear non-proliferation that falls short of complete denuclearization, but is still better than other alternatives — such as nuclear confrontation, an endless nuclear arms race or forced regime change in North Korea.

Xi’s Performance and Prospects

How well has Xi conducted his summit diplomacy so far? He has performed reasonably well and achieved a few objectives. First, he was able to protect China’s core national interests amid a dizzying flurry of summit meetings related to the Korean Peninsula. Second, he made it clear that no important issue can be settled in Korea without China’s direct participation or at least China’s tacit consent. Third, he improved his relations with Kim Jong Un in dramatic fashion and emerged as Kim’s indispensable benefactor. Fourth, he managed a co-operative relationship with Moon and left a door open for renewing a “strategic co-operative partnership” with South Korea. Moreover, he demonstrated that China is neither a bystander nor a spoiler in Korean affairs. As Xi assured Trump in their telephone discussions on Nov. 1, 2018, China is prepared to play a “constructive role” in promoting peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula. Does Xi have a grand strategy on the Korean Peninsula? If he does, it may be a long-range dream to prevent any foreign power from exerting a dominant role over Korean affairs and to induce both Koreas — or a unified Korea — to move into China’s sphere of influence. For all practical purposes, however, this dream is difficult to realize, in part because China lacks enough hard and soft power to do so. In fact, Xi faces a variety of actual and potential obstacles to his dream. Chief among them is the resistance from highly nationalistic and independent-minded political leaders in both Koreas and the countervailing forces represented by the US and Japan. In the meantime, Xi may be satisfied with China’s realistic two-Korea policy. He will make sure that North Korea remains in China’s orbit as long as possible and that he, in co-operation with Kim, will try to disengage South Korea from America’s grip whenever an opportunity presents itself. It is in China’s interest to sustain a balance of power on the Korean Peninsula.

It is likely that China and the US will engage in a mixture of conflict and co-operation over Korean affairs for a long time. If Xi and Trump continue to escalate trade and other disputes, it will introduce a destabilizing factor to the equation of China’s relationship with both Koreas. If, however, they find it in their national interests to agree on a modus operandi, it will certainly help stabilize the overall atmosphere for conducting productive summit diplomacy by each nation. So long as his grand strategy remains out of reach, Xi will pursue a pragmatic and cautious policy to sustain co-operative relations with both Koreas. He sees no “zero sum” situation in his two-Korea policy. As he becomes ever more comfortable with bilateral and multilateral meetings with other heads of state, he will continue to rely on summit diplomacy as one useful instrument to deal with foreign affairs. The Korean Peninsula will be no exception.

By Chae-Jin Lee

(Global Asia)