Great Indus Civilization

Experts say ‘Moen Jo Daro’ dates back to Bronze Age

Preliminary analyses of cores obtained from World Heritage site of great Indus Civilization, known as ‘Moen Jo Daro’ or the ‘Mound of Dead’ (as the original name is unkown) located in Sindh province of Pakistan has confirmed that the ancient city dates back to Bronze Age.

Sindh Department of Culture, Tourism & Antiquities had initiated the Dry Core Drilling program at the site in the year 2015-16.

“MohenjoDaro is potentially the largest settlement of this time frame (Bronze Age) in the world and its period of florescence spanned the period 2600-1900 B.C,” Dr. Joseph Schuldenrein of Geoarchaeology Research Associates, New York, USA and Dr. Michael Jansen, of GU-Tech University of Technology, Muscat Oman, the two principal investigators, opined at a press conference held in Karachi, capital of Sindh province, recently.

Previous work by scholars like Raikes, Lambrick, and others including the cores obtained by some organizations were partially studied by these geoarcheologists.

Interpretations offered strong indications that the site was considerably larger than formerly acknowledged by archaeologists and that the sediments that blanketed the terrain near the known city-center were both deep and of alluvial origin. Based on earlier fieldwork and remote imagery, it was hypothesized that major (and intact) portions of the settlement lay buried beneath many meters of flood deposit.

In 2012 UNESCO commissioned a study to identify the center and buffer zone of the city (Moen Jo Daro) to delimit its margins and to provide an overview of the buried contexts of the ancient and extended settlement. The Technical Consultative Committee (TCC) formulated the Dry Core Drilling program and undertook a systematic drilling of approximately 60 cores that were aligned along transects crossing the site and its general vicinity. Several sets of cores had been excavated along the project footprint over the years, but none were analyzed in great detail.

The objectives were to identify processes and periods of flooding that may have accounted for technical innovations that would have allowed for permanent settlement in proximity to the Indus River. Additionally, it was necessary to understand the stream behavior and flooding processes that affected the human settlement and the landscape use of the site. As the results of the dry core drilling began to take shape, it was decided that the flood deposits should be radiocarbon dated in order to develop a history of the alluviation and its connection to the occupation of Moen Jo Daro.

Dr. Joseph Schuldenrein was brought to run a series of radiocarbon dates and to explore the relationship between flood activity and the anthropogenic deposits that were preserved in a large number of the deep cores. Initial results showed that the antiquity of floodplain and delta complexes in which Mohenjodaro was centered extends as early as the Late Pleistocene (ca. 17,000 B.P.) and continued well into the Holocene (ca. 2000 B.P.).

Dr. Joseph Schuldenrein was brought to run a series of radiocarbon dates and to explore the relationship between flood activity and the anthropogenic deposits that were preserved in a large number of the deep cores. Initial results showed that the antiquity of floodplain and delta complexes in which Mohenjodaro was centered extends as early as the Late Pleistocene (ca. 17,000 B.P.) and continued well into the Holocene (ca. 2000 B.P.).

These are the first radiocarbon dates of the Moen Jo Daro landscape. Early observations suggest that extensive meandering dominated the fluvial regime of the delta. These results confirm the signature of extensive meandering activity and a complex series of stream migrations whose history involved lateral channel displacement and isolated periods of ponding and basin formation.

An understanding of the relationship between human geography and landscape change is the key to reconstructing the combined history of human occupation and preservation of the archaeological components at this site.

“We are in the early stages of assembling the geological and archaeological records.This work underscores the need to expand our research in the form of a 3 year proposal to further investigate all elements of the history of Mohenjodaro with an emphasis on the complex relationships between the core city, its secondary locations and an alluvial landscape whose history is only now beginning to take shape,” experts told.

Moen Jo Daro is considered as one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization, and one of the world’s earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Norte Chico. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated an UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980.

The city’s original name is unknown. The ruins of the city remained undocumented for around 3,700 years until R. D. Banerji, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India, visited the site in 1919–20, identifying the Buddhist stupa (150–500 CE) known to be there and finding a flint scraper which convinced him of the site’s antiquity. This led to large-scale excavations of Moen Jo Ddaro led by Kashinath Narayan Dikshit in 1924–25, and John Marshall in 1925–26. In the 1930s, major excavations were conducted at the site under the leadership of Marshall, D. K. Dikshitar and Ernest Mackay. Further excavations were carried out in 1945 by Ahmad Hasan Dani and Mortimer Wheeler. The last major series of excavations were conducted in 1964 and 1965 by Dr. George F. Dales. After 1965 excavations were banned due to weathering damage to the exposed structures, and the only projects allowed at the site since have been salvage excavations, surface surveys, and conservation projects. However, in the 1980s, German and Italian survey groups led by Dr. Michael Jansen and Dr. Maurizio Tosi used less invasive archeological techniques, such as architectural documentation, surface surveys, and localized probing, to gather further information.

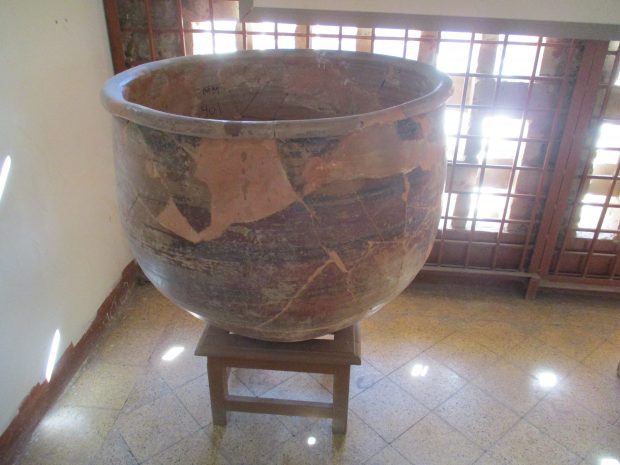

Moen Jo Daro has a planned layout with rectilinear buildings arranged on a grid plan. Most were built of fired and mortared brick; some incorporated sun-dried mud-brick and wooden superstructures. The covered area of Moen Jo Daro is estimated at 300 hectares.

A bronze statuette dubbed the “Dancing Girl”, 10.5 centimetres (4.1 in) high and about 4,500 years old, was found in 1926.

John Marshall at that time described the figure as “a young girl, her hand on her hip in a half-impudent posture, and legs slightly forward as she beats time to the music with her legs and feet.” The statue led to two important discoveries about the civilization: first, that they knew metal blending, casting and other sophisticated methods of working with ore, and secondly that entertainment, especially dance, was part of the culture.

In 1927, a seated male soapstone figure was found in a building with unusually ornamental brickwork and a wall-niche. Though there is no evidence that priests or monarchs ruled Moen Jo Daro, archaeologists dubbed this dignified figure a “Priest-King.” The sculpture is 17.5 centimetres (6.9 inches) tall, and shows a neatly bearded man with pierced earlobes and a fillet around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or head-dress; his hair is combed back. He wears an armband, and a cloak with drilled trefoil, single circle and double circle motifs, which show traces of red.

Among hundreds of other things including pottery, ornaments and toys, a seal was discovered bearing the image of a seated, cross-legged and possibly ithyphallic figure surrounded by animals. The figure has been interpreted by some scholars as a yogi, and by others as a three-headed “proto-Shiva” as “Lord of Animals”.