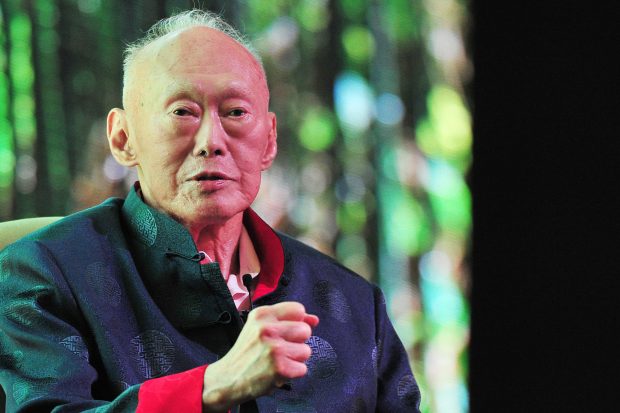

Press Watch – Singapore:

Singapore’s former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew speaking at the Standard Chartered Singapore Forum in Singapore. (Xinhua)

Singapore’s leader Lee Kuan Yew, who dominated the political scene from 1959, when he first came to power, till his death on March 23rd, 2015, corralled the press as an instrument to help realise his own nation-building agenda.

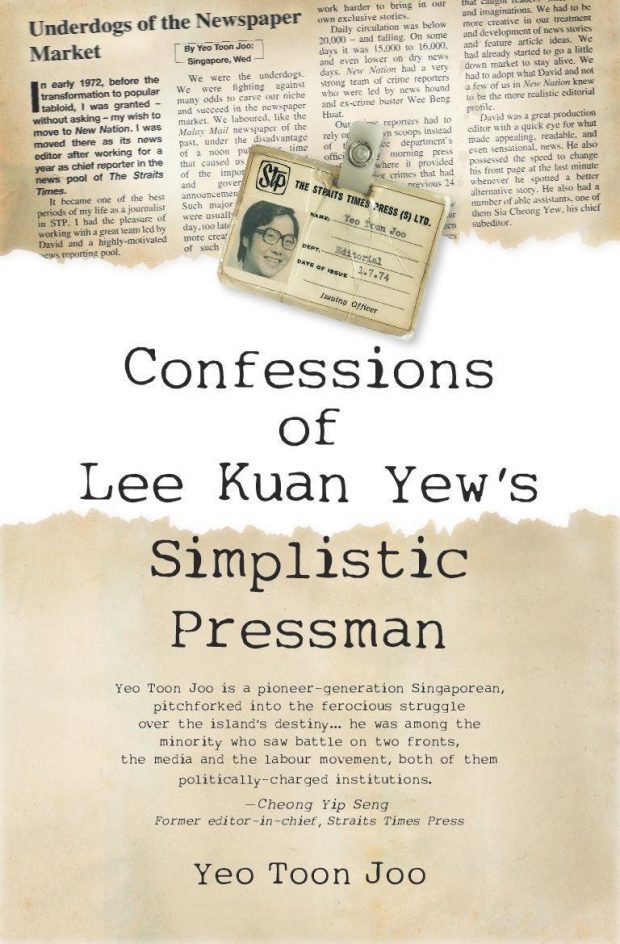

Retired newsman Yeo Toon Joo, who spent 12 years (1963-1975) in an English major daily, The Straits Times, and a defunct tabloid, New Nation, has given insider’s account of how Prime Minster Lee Kuan Yew (from now on: LKY) went about taming the domestic press in his self-published book, Confessions of Lee Kuan Yew’s Simplistic Pressman.

His central thesis is this: “I was convinced at an early stage that he felt pressmen were to be used primarily for his political objectives, and not for a free play of ideas and views, or the building up of a population of thinking and questioning Singaporeans.”

Yeo noted that for starters, Lee had a very low opinion of journalism as a profession.

This came through, he noted, in the Prime Minister’s observation as guest of honour at the Singapore Press Club annual dinner in 1972 that journalists often did not bind to rules of conduct. He also stated that, unlike doctors, surgeons, lawyers or engineers, reporters in the country did not have to pass stringent professional examinations.

Most tellingly, Yeo mentioned LKY’s aggressive manner in the 1960s when after making a speech, LKY warned reporter Cheong Yip Seng: “If you print this, I will break your neck.

In the 1970s, the Straits Times editor-in-chief T.S. Khoo was summoned to see Lee Kuan Yew in his City Hall office to answer for perceived poor judgment in news report and features as well as use of photographs. Khoo told his editors (as said by Yeo) that “there had never been any real dialogue between him and LKY but more of just angering the leader. “Boy, I had such a walloping from Chief Thunder Cloud,” Khoo was quoted to have said.

A Straits Times photograph in its afternoon daily New Nation offended LKY for showing a happy family with three children. “He (LKY) regarded it as an attempt to sabotage the government’s Stop at the Two population planning campaign. Lee also took umbrage at Yeo for running a series on the homosexuals in Singapore in the New Nation tabloid.

In hindsight, Lee’s perception of the right role of the media was spelled out in his address to the International Press Institute general assembly in Helsinki on 9 June 1971: “Freedom of the news media must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore, and to the primacy of purpose of an elected government.”

Yeo added, “In the half century he had held sway over Singapore society and its politics, the Press was to play to the tune of the Prime Minister.”

Over time, Yeo realised that LKY had become convinced that it was easier to control than to influence the mass media. Any newspaper which dared to defy the official line would be accused of “taking on” the government and face Lee’s blowback. Yeo reckoned that Lee justified his press control on the basis of his being the elected leader, through the people’s mandate, given authority to govern Singapore.

But Yeo disputed this, asserting that the press not being elected does not disqualify it from reporting and commenting on news events and developments in the country—and on the actions of the nation’s political leaders.

Lee’s antagonistic relations with the press came to a head in the Singapore Herald episode. The newspaper got into trouble when it carried letters with readers’ complaints over national service in which citizens serve two to two-and-a-half years in the armed forces. It was a topic of taboo as conscription was seen as vital to Singapore’s defence and survival

Yeo also mentioned Lee Kuan Yew’s crackdown on Chinese newspaper Nanyang Siang Pau for its report on the decline of Chinese-medium schools, accusing it of stoking up chauvinism and of playing up communist achievements. The family-owned paper was seen to be painting the government as oppressors of Chinese language and education.

Summing up his account, Yeo said LKY carried out a major restructuring the media industry to secure total control of all mass media organisations in Singapore. In 1984, the government passed the landmark Newspaper and Printing Presses Act making it compulsory for newspapers to be publicly listed. “He was designer, director and undertaker.” Yeo concluded.

“In 1984, Lee Kuan Yew delivered his coup de grace in taking over the venerable Straits Times Press Ltd.; one of the world’s most profitable newspaper. With one stroke of the pen—or was it just a word—he cornered all the major newspaper publishing companies in Singapore into one umbrella organisation, Singapore Press Holdings Ltd.

Under the Act, management shares in newspapers were allocated to banks and other Establishment figures, thereby giving the government effective control of mass media.

In lamenting the loss of an independent press in Singapore, Yeo said: “It was sad but inevitable. Sadder still is then Singapore Government’s loss of a credible platform to communicate with the population of Singapore, weakened further by the advent of social media.”